Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

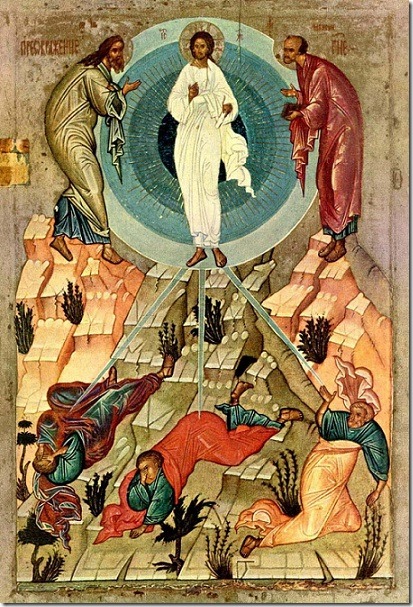

Sunday’s Gospel narrates the Transfiguration. In his Gospel Luke gives the reason why Jesus “went up the mountain” that day: He went up “to pray.”

HE WENT UP THE MOUNTAIN TO PRAY

Genesis 15:5-12, 17-18; Philippians 3:17-4:1; Luke 9:28b-36

Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa

Sunday’s Gospel narrates the Transfiguration. In his Gospel Luke gives the reason why Jesus “went up the mountain” that day: He went up “to pray.”

It was prayer that made his raiment white as snow and his countenance splendid like the sun. Following the program we announced in our commentary for last Sunday, we would like to take this episode as a point of departure for examining how prayer takes up Christ’s whole life and what this prayer tells us about the profound identity of his person.

Someone has said: “Jesus is a Jewish man who does not regard himself as identical with God. Indeed, one does not pray to God if one is God.” Leaving aside for a moment what Jesus thought about himself, this claim does not take account of an elementary truth: Jesus is also a man and it is as a man that he prays.

God, of course, could not have hunger or thirst either, or suffer, but Jesus hungers and thirsts and suffers because he is human.

On the contrary, it is precisely Jesus’ prayer that allows us to consider the profound mystery of his person. It is a historically attested fact that in prayer Jesus turns to God calling him “Abba,” that is, dear father, my father, papa. This way of addressing God, although not unknown before Jesus’ time, is so characteristic of Jesus that we are obliged to see it as evidence of a singular relationship with the heavenly Father.

Let us listen to this prayer of Jesus reported by Matthew: “At that time Jesus said in reply, ‘I give praise to you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, for although you have hidden these things from the wise and the learned you have revealed them to mere children. Yes, Father, such has been your gracious will. All things have been handed over to me by my Father. No one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son wishes to reveal him'” (Matthew 11:26-27).

Between Father and Son there is, as we see, total reciprocity, “a close, familiar relationship.” In the parable of the murderous tenants of the vineyard this singular relationship of father and son that Jesus has with God again clearly emerges; it is a relationship different from all the others who are called “servants” (cf. Mark 12:1-10).

At this point, however, an objection is made: Why then did Jesus never openly give himself the title “Son of God” during his life, but instead always spoke of himself as the “Son of man”? The reason for this is the same as that for which Jesus never calls himself the Messiah, and when others call him this name he is reticent, or even forbids them to spread it around. Jesus acted in this way because those titles were understood by the people in a very precise way that did not correspond to the idea that Jesus had of his mission.

Many were called “Son of God”: kings, prophets, great men. The Messiah was understood to be the one sent by God who would lead a military fight against Israel’s enemies and rulers. It was in this direction that the demon tried to push Jesus in the desert.

His own disciples did not understand this and continued to dream of a destiny of glory and power. Jesus did not understand himself to be this type of Messiah: “I did not come to be served,” he said, “but to serve.” He did not come to take anyone’s life away, but rather “to give his life in ransom for many.”

Christ first had to suffer and die before it was understood what kind of Messiah he was. It is symptomatic that the only time that Jesus proclaims himself Messiah is when he finds himself in chains before the High Priest, about to be condemned to death, without any other possibility of equivocations. “Are you the Messiah, the Son of the Blessed God?” the High Priest asks him, and he answers: “I am!” (Mark 14:61ff).

All the titles and categories with which men, friends and enemies, try to saddle Jesus during his life appear narrow, insufficient. He is a teacher, “but not like other teachers,” because he teaches with authority and in his own name. He is the son of David, but also David’s Lord; he is greater than a prophet, greater than Jonah, greater than Solomon.

The question that the people posed, “Who on earth is he?” expresses well the sentiment that surrounded him like a mystery, something that could not be humanly explained.

The attempt of some scholars and critics to reduce Jesus to a normal Jew of his time, who would not have in fact said or done anything special, is in total contrast to the most certain historical data that we have of him. Such views can only be understood as guided by a prejudicial refusal to admit that something transcendent could appear in human history. These reductive approaches to Jesus cannot explain how such an ordinary being became — as these same critics say — “the man who changed the world.”

Let us now go back to the episode of the Transfiguration to draw from it some practical teaching. Even the Transfiguration is a mystery “for us,” it hits close to home.

In the second reading St. Paul says: “The Lord Jesus transfigured our miserable body, conforming it to his glorious body.” Tabor is an open window on our future; it assures us that the opacity of our body will one day be transformed into light. But Tabor also tells us something about the present. It highlights what our body already is, beneath its miserable appearance: the temple of the Holy Spirit.

For the Bible the body is not an inessential element of human beings; it is an integral part. Man does not have a body, he is a body. The body was created directly by God, assumed by the Word in the incarnation and sanctified by the Spirit in baptism.

The man of the Bible is enchanted by the splendor of the human body: “You formed my inmost being; you knit me in my mother’s womb. I praise you, so wonderfully you made me” (Psalm 139). The body is destined to share the same glory in eternity as the soul. “Body and soul: either they will be two hands joined in eternal adoration or two wrists bound together in eternal captivity” (Charles Péguy).

Christianity preaches the salvation of the body, not salvation from the body, as the Manichean and Gnostic religions did in antiquity and as some Eastern religions do today.

And what can we say to those who suffer? What can we say to those who witness the deformation of their own bodies or those of loved ones? The most consoling message of the Transfiguration is perhaps for them. “He will transfigure our miserable body, conforming it to his glorious body.”

Bodies humiliated by sickness and death will be ransomed. Even Jesus will be disfigured in the passion, but will rise with a glorious body with which he will live for eternity and, faith tells us, with which he will meet us after death.

Jesus listens to the Law and the Prophets

Benedict XVI

On the Second Sunday of Lent, the Evangelist Luke emphasizes that Jesus went up on the mountain “to pray” (9: 28), together with the Apostles Peter, James and John, and it was “while he prayed” (9: 29) that the luminous mystery of his Transfiguration occurred.

Thus, for the three Apostles, going up the mountain meant being involved in the prayer of Jesus, who frequently withdrew in prayer especially at dawn and after sunset, and sometimes all night.

However, this was the only time, on the mountain, that he chose to reveal to his friends the inner light that filled him when he prayed: his face, we read in the Gospel, shone and his clothes were radiant with the splendour of the divine Person of the Incarnate Word (cf. Lk 9: 29).

There is another detail proper to St Luke’s narrative which deserves emphasis: the mention of the topic of Jesus’ conversation with Moses and Elijah, who appeared beside him when he was transfigured. As the Evangelist tells us, they “talked with him… and spoke of his departure” (in Greek, éxodos), “which he was to accomplish at Jerusalem” (9: 31).

Therefore, Jesus listens to the Law and the Prophets who spoke to him about his death and Resurrection. In his intimate dialogue with the Father, he did not depart from history, he did not flee the mission for which he came into the world, although he knew that to attain glory he would have to pass through the Cross.

On the contrary, Christ enters more deeply into this mission, adhering with all his being to the Father’s will; he shows us that true prayer consists precisely in uniting our will with that of God. For a Christian, therefore, to pray is not to evade reality and the responsibilities it brings but rather, to fully assume them, trusting in the faithful and inexhaustible love of the Lord.

For this reason, the verification of the Transfiguration is, paradoxically, the Agony in Gethsemane (cf. Lk 22: 39-46). With his impending Passion, Jesus was to feel mortal anguish and entrust himself to the divine will; his prayer at that moment would become a pledge of salvation for us all.

Indeed, Christ was to implore the Heavenly Father “to free him from death” and, as the author of the Letter to the Hebrews wrote: “he was heard for his godly fear” (5: 7). The Resurrection is proof that he was heard.

Dear brothers and sisters, prayer is not an accessory or “optional”, but a question of life or death. In fact, only those who pray, in other words, who entrust themselves to God with filial love, can enter eternal life, which is God himself.

During this Season of Lent, let us ask Mary, Mother of the Incarnate Word and Teacher of the spiritual life, to teach us to pray as her Son did so that our life may be transformed by the light of his presence.

Angelus, 7.3.2007