Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

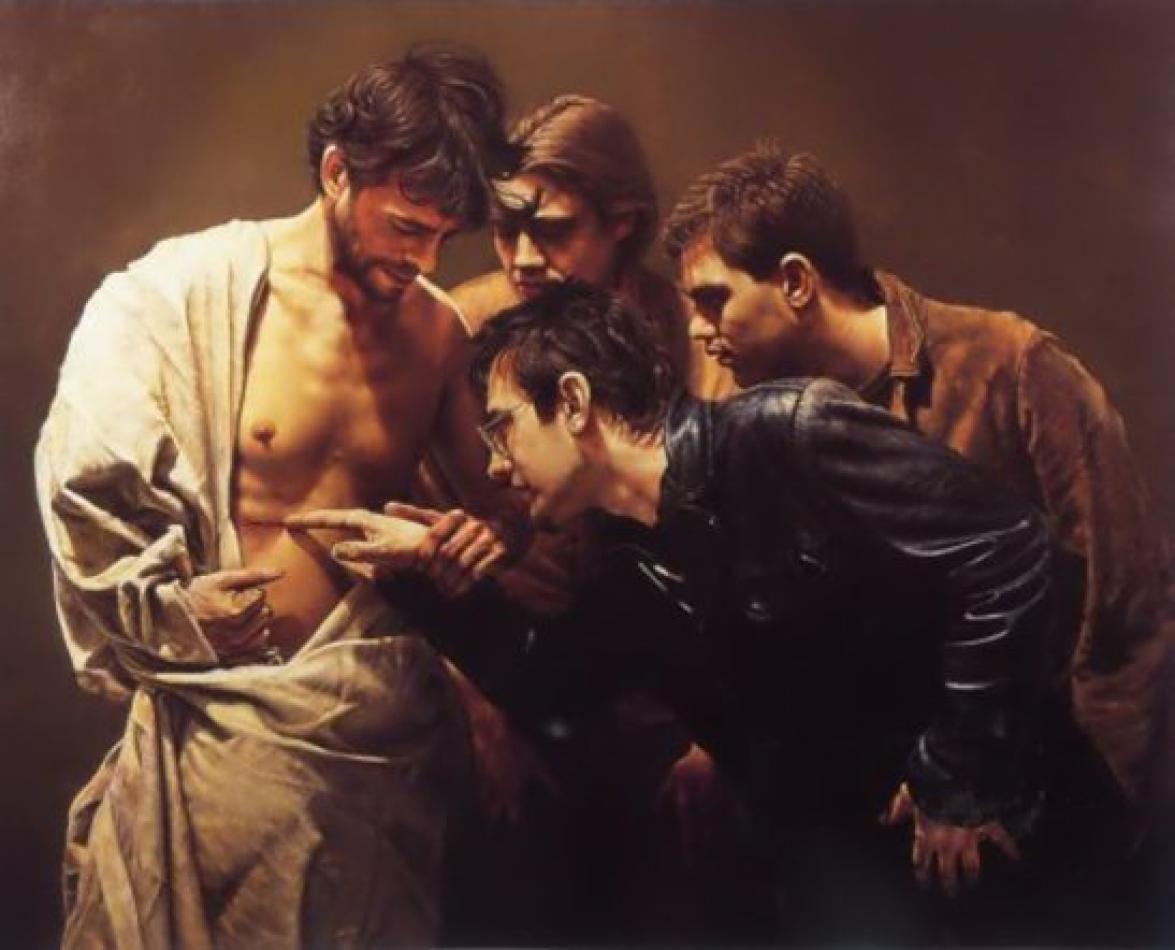

On our Lenten journey, the past Sundays have focused on proclaiming God’s mercy and calling us to conversion. Today, this path reaches its climax with the Gospel of the woman caught in the act of adultery. [...]

“Go, and from now on do not sin any more!”

John 8:1-11

On our Lenten journey, the past Sundays have focused on proclaiming God’s mercy and calling us to conversion. Today, this path reaches its climax with the Gospel of the woman caught in the act of adultery. This text (John 8:1-11) has had a troubled history: it is absent from the oldest manuscripts, ignored by the Latin Fathers until the 4th century, and never commented upon by the Greek Fathers of the first millennium. It’s like a page torn from its original context and inserted here into John’s Gospel. However, many scholars believe it may have originally belonged to St Luke, the evangelist of mercy.

This passage proved uncomfortable, as it clashed with the strict penitential discipline of the early centuries, when serious sins—murder, adultery, and apostasy—could only be forgiven once in a lifetime. Deep down, even today we struggle to move beyond the logic of justice and fully embrace the mindset of mercy.

What do you think?

The scene unfolds one morning in the Temple, where Jesus was teaching the people. The scribes and Pharisees bring him a woman caught in adultery, place her in the middle, and say to him: “Master, this woman was caught in the very act of committing adultery. Now, in the Law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. What do you say?”

The evangelist notes that they said this to test him. The woman is just a pretext: the real target is Jesus himself—and his mercy. They want to see how he will handle this situation. If he hesitates to apply the Law, they can accuse him before the Sanhedrin; but if he calls for her condemnation, he will lose the favour of the people, who see him as a kind and compassionate teacher.

The practice of executing adulterers was common in the ancient Near East—a barbaric custom which, sadly, still exists today in some Islamic countries. It is also found in Leviticus 20:10: “If a man commits adultery with another man's wife—both the adulterer and the adulteress are to be put to death” (cf. Deut 22:22). It served as a deterrent, but in practice, it was not strictly applied in Jesus’ time. Notice, too, that only the woman is brought forward. Where is the adulterer? The Law is not being applied impartially.

Jesus, instead of replying, bends down and begins to write with his finger on the ground in silence. What does he write? The sins of her accusers, as St Jerome suggests? Many speculations have been made! But perhaps the explanation is far simpler: doodling on the ground may have been a way to gain time, reflect, prepare an answer—or even release the irritation provoked by their question.

We find the expression “writing with the finger” only three times in Scripture. The first is in Exodus 31:18: the finger of God writes the Law on the stone tablets; the second, in the parallel passage of Deuteronomy 9:10; and the third, in Daniel 5, when a finger writes three words on the wall of the banquet hall where King Belshazzar is desecrating the sacred vessels taken from the Temple of Jerusalem.

What does Jesus write? The new law of love and mercy—written in the dust from which we were made, upon the fragility of our flesh, within our lives marked by unfaithfulness and sin. It is the new law God promised to write on the heart of every believer (Jeremiah 31:31-34).

Let the one who is without sin throw the first stone!

Jesus kept silent. But as they continued to question him, he straightened up and said: “Let the one among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.” Then, stooping down again, he wrote on the ground.

Jesus does not deny the Law, but he calls them to apply it first to themselves. All await someone “without sin” to cast the first stone. But none does. One by one, they leave. They had arrived together, full of confidence; now they leave, confused, slipping away in silence—starting with the elders. The stones are left on the ground. So too are the masks of those who had set themselves up as judges.

The woman’s accusers are forced to look within themselves, to confront the Law of Moses in their own lives. And they find themselves in her place. When we truly look inside ourselves, we can no longer condemn anyone. Often, unconsciously, when we fail to overcome the evil within us, we try to fight it outside—in others—and thus feel justified. This is when the mob mentality takes over: it only takes one person to throw the first stone, and the rest will follow. In this way, no one takes responsibility for the violence committed. If we do not fight the evil within, the enemy will always be someone else—someone to eliminate.

Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?

All have gone. Whether defeated or convinced, we do not know. And the woman remained there, alone, in the centre. On one side, misery; on the other, mercy, as St Augustine comments. Then Jesus stood up again, looked at her, and asked: “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” And she replied, “No one, Lord.”

Jesus “stood up” to look at her. According to the literal sense of the Greek verb, he “straightened himself up,” not “stood up.” He remains seated, low down: he does not look down on us, but looks up from below—for he has come to take the lowest place.

Then, the two gazes meet: hers, ashamed, fearful, and sorrowful; his, pure, gentle, and compassionate. It is a different gaze—one she has never known.

“It is the gaze that saves,” says Simone Weil. The Christian is called to reflect this gaze each morning—to realise how deeply loved they are, and to purify their view of others and the world.

Jesus calls her “Woman,” just as he addresses his own Mother in John’s Gospel. In doing so, he restores her dignity. And she, the Woman, calls him “Lord”—the Lord who saved her life.

This woman represents all of us, “adulterers,” unfaithful to the Bridegroom. We, too, belong to the “adulterous and sinful generation” (Mark 8:38).

Go, and from now on do not sin any more!

Then Jesus said: “Neither do I condemn you!” For “God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him.” (John 3:17).

“Go, and from now on do not sin any more!” You are free from your past. Life is once again placed in your hands. You can begin anew!

These same words are addressed to us this Lent. So often, our lives are entangled with the past: with our failures, regrets over missed opportunities, our sins… But the Lord says: “Do not remember the former things, nor consider the things of old. See, I am doing a new thing—now it springs forth, do you not perceive it?” (Isaiah 43:16-21 – First Reading).

So let us imitate St Paul: “Forgetting what lies behind and straining towards what lies ahead, I press on towards the goal.” (Philippians 3:8-14 – Second Reading).

Fr Manuel João Pereira Correia, MCCJ

God Saves, He does not Condemn

Gospel reflection – John 8:1-11

Fernando Armellini

If reading a book we happen to find that a page has been torn, probably we would think that the story had to contain unreasonable details and that a pious hand, to prevent trouble for some less mature readers, has removed the offending text. Well, in the early centuries of the Church, when the books of the New Testament were transcribed, from almost all copies of the Bible the page of today’s Gospel was removed..

Luke must have composed it (the theme, style, language are his) and its natural place is at the end of Chapter 21. It is there, in fact, that it is placed by a large group of ancient manuscripts. Certainly it was not John and no one knows how it entered the eighth chapter of the Fourth Gospel. Perhaps because, after a few verses, there is the phrase of Jesus: I do not judge anyone (Jn 8:15). In any case it is clear that this text has had a rather troubled history.

The reason? St. Augustine gave his a bit dismissive and obvious reason: “Some members of little faith, or rather enemies of the true faith, probably feared that the welcome Jesus gave to the sinful woman grant immunity to their women.” Simply put: husbands, parents, community leaders must have thought that the words of Jesus “I do not condemn you” could be misunderstood and then… it is better to ignore the story.

The real reason of suspicion for this episode, however, is perhaps another: the penitential practice that had been established in the early centuries of the Church.

With the increased number of Christians, in the first centuries quality had lapsed and a certain laxity that led to justify any behavior and retained all as licit was introduced. In response a belief spread wide and far that, against those who sinned seriously, the church could act granting pardon, yes, but only once in life. Repeat offenders has only to wait for the severe judgment of God. Clearly the rigorists preferred to put aside, not to give any importance to the episode of the adulteress.

Those who advocated a more gentle and understanding attitude gladly recalled this story. In the apostolic constitutions—an important book of the fourth century—it is recommended to the Bishop to imitate what Jesus did “to the woman who had sinned and that older people had set before him.”

Looked with a certain suspicion or with sympathy, the passage still remained. Then it was necessary to come up with an explanation for the offending sentence. Someone would have preferred that Jesus did not utter: “I do not condemn you.”

He had begun by saying: see how good is the Lord? The woman had to be stoned, but since she was more than repentant, Jesus first defended her and then forgave her.

But if it was so, why would the fact raise many objections to the point of trying to delete it from the Gospel? Would there be anything strange if Jesus had forgiven a repentant sinner? This is where the crux of the problem lies: there is absolutely nothing to suppose that she had repented.

Let us not confuse her with the sinner Luke speaks about in another part of his Gospel. That one repented: wept, anointed the feet of Jesus and dried them with her hair (Lk 7:36-50), but the adulteress in today’s Gospel has not done any of this. She was caught in the act, grabbed, threatened, perhaps beaten, then was thrown in front of Jesus. Nothing else. Of course, she must have been shocked, scared, ashamed. But supposing that, in those conditions, she may have thought of an “act of perfect contrition” is pure fantasy!

Why bother to excuse Jesus? He has no need of our justifications. Does it surprise us? Does it upset us? Fine. We may not even agree with his behavior, but you cannot deny, modify, minimize the scope of the fact. Let’s figure it out.

A woman is caught… while she was not reciting the rosary! It is strange that the man was not also grabbed. It is the same old story: aggression, violence, passion is unleashed always on the weakest; the strong always manage somehow to escape and get away with it.

The law punished adultery with death (Lev 20:10). In practice, however, the judges were not severe, always shut one eye and never condemned to death. Moreover, when the Bible imposed this penalty, it does not intend the real execution. It only underscores the seriousness of the crime. Just think that it is also provided for one who beats his own father (Ex 21:15).

We do not know who were the authors of the morality of Jerusalem, but one thing is certain: then, as now, there were people obsessed by the fact that others committed sexual sins. How do you explain this fanaticism in the defense of public decency? Are these moralizers really innocent and pure? Why do they enjoy putting in public the sins of others? Maybe these are people who would like to do the same things, but, not being able to, they attacked those who practice them.

Someone in this group of moral vigilance must have made the proposal: and if we drag this w… (sinful woman!) to the Galilean teacher? Yes, from the man who is always on the side of these corrupt people? He will certainly not have the courage to defend her! You will see how he will be embarrassed when forced to speak out against “his friends” (Mt 11:19)!

They find him sitting in the yard of the temple, surrounded by many people who listen to him carefully. They drag the woman in the middle, “standing in front of all” and, with a smile full of innuendo, they ask him: “Master, the law orders that such women be stoned to death, what do you say?”

Jesus does not respond. He bends down and begins to write on the ground. What does he write? Opinion—which spread from St. Jerome—that he wrote the sins of the accusers is meaningless and no one supports it. However the custom among the Semitic peoples of scribbling on the ground while one is thinking or want to release tension or control the irritation before another who asks absurd or provocative questions is well documented.

Jesus could get out of trouble in a very simple way: by inviting the accusers to address the legitimate judges. The court of the Sanhedrin is not more than a hundred meters away. But this would mean abandoning the woman that the “defenders of public morality” now consider a trophy, a prey. For this he raises his head and says: “Let anyone among you who has no sin be the first to throw a stone at her.” Then he bends again and continues to draw lines on the ground.

At that point the audience start to not feel more at home: they have been exposed. Their hypocrisy has been stripped. They lower their eyes, trying to take a cavalier attitude, to hide the embarrassment and shame. They move away, starting with the elders, the “priests”—says the Greek text. None remain except Jesus and the woman alone.

Let us consider well the position of the two. The woman was standing, as was the case with the accused during trials (v. 3) and Jesus was sitting (v. 2). Throughout the dialogue the position is the same: Jesus bends (v. 6), raised his head (v. 7) and leans back (v. 8), but remains always seated and the woman standing, “there in the middle” (v. 9).

In verse 10 of our text says, “Then Jesus stood up,” giving the idea that, to give judgment, he stood. Not so. The verb used is the same as in verse 7 and has been translated as “raised his head.” Jesus has remained where he was, down, in the position of the servant, not the judge who looks down on those who did wrong. He only lifted his head to talk to the woman, with the sweetness of his gaze, the tenderness of God that does not condemn anyone. They’ve all gone—says the text—thus, together with prosecutors, the crowd and even the disciples left. Only Jesus remained to pronounce his surprising judgment: no condemnation.

The Gospel emphasizes that the first to leave were the elders. Maybe they are the more mature people in the community who are invited to make an examination of conscience. Often they are the ones who delight in “throwing stones” with gossips and slanders.

If Jesus does not judge or condemn, then does it mean that sin is a small thing? To behave well or badly does not matter?

No! Sin is a very serious evil because it destroys the lives of those who commit it. Jesus does not say to the woman: “Go in peace, you did wrong to betray your husband, do not repeat the error of ruining your life for a moment of pleasure.”

Nobody hates sin more than Jesus, because nobody loves people more than him. However he does not condemn those who make mistakes (and he allows nobody to throw stones) in order not to add more evil to that which the sinner has already done.

Maybe he does not condemn now, but one day will he judge and punish his children who commit evil? Let’s pay attention. Jesus does not say to the sinful woman: “For this time I do not condemn you.” This would be good also for purists of the first centuries. He says: “I do not condemn you”, neither today, nor tomorrow, not ever.

This page of the Gospel today does not disturb less than yesterday. It does not leave tranquil those who continue to claim the right, from the unassailable fortress of their respectability, of hurling stones no longer with the hands, but defaming, isolating, uttering harsh judgments, fueling distrust, spreading gossips. Jesus does not tolerate anyone who throws these painful and cruel stones against those who hold with difficulty, bent under the weight of their own mistak

Fernando Armellini

Italian missionary and biblical scholar

https://sundaycommentaries.wordpress.com