Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

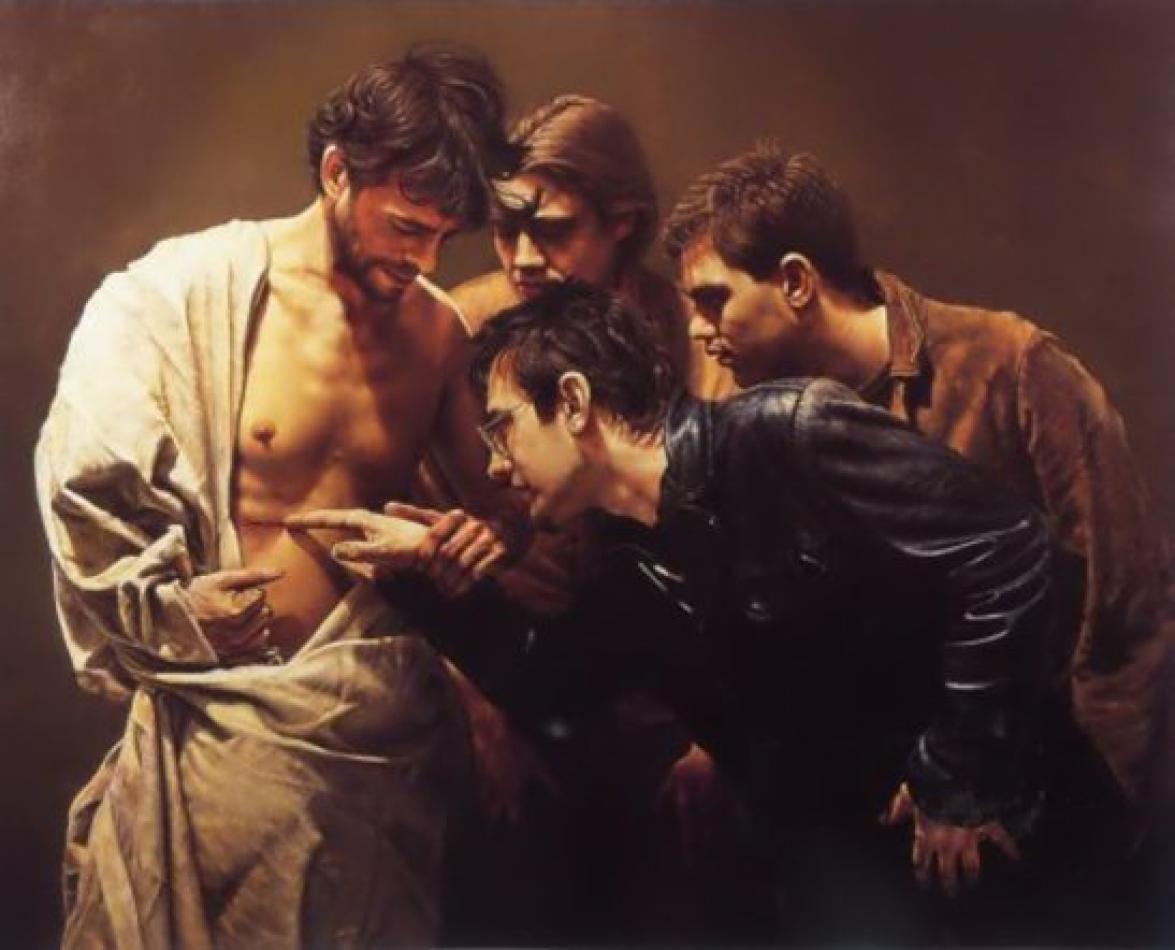

The healing of the blind man from Jericho is the last miracle narrated in the Gospel of Mark. This story follows Jesus’ three predictions about His passion, death, and resurrection, accompanied by related teachings given to the disciples. These predictions and teachings form the backbone of the central part of the Gospel of Mark. [...]

“Rabbuni, let me see again!”

Mark 10:46-52

The healing of the blind man from Jericho is the last miracle narrated in the Gospel of Mark. This story follows Jesus’ three predictions about His passion, death, and resurrection, accompanied by related teachings given to the disciples. These predictions and teachings form the backbone of the central part of the Gospel of Mark.

We are in Jericho, the last stop for Galilean pilgrims traveling along the Jordan road, heading toward Jerusalem for Passover. The distance between Jericho and Jerusalem is about 27 kilometers. The route passes through desert and mountainous terrain, with a significant elevation change. In fact, Jericho is about 258 meters below sea level, while Jerusalem is located about 750 meters above sea level. The journey is thus an uphill and rather strenuous one, a relevant detail in the context of Jesus’ journey to Jerusalem, as described by Mark.

The evangelist pays particular attention to the figure of Bartimaeus, son of Timaeus, likely a well-known person in the early community. Besides mentioning his father’s name, the evangelist carefully describes his actions: “He threw off his cloak, jumped up, and went to Jesus.” The cloak, considered the only possession of the poor, also represented a person’s identity. Therefore, “throwing off the cloak” symbolizes stripping oneself. St. Paul, in the Letter to the Ephesians (4:22), speaks of “putting off the old self.” Bartimaeus is the only case where it is said that the healed person follows Jesus on the way. The Desert Fathers saw in this an allusion to the baptismal liturgy: before being baptized, the catechumen would take off their garment, descend naked into the baptismal font, and, upon emerging, be clothed with a white robe.

Reflections

1. Bartimaeus, a figure of the disciple: symbolic significance of the miracle

The central part of the Gospel of Mark (chapters 8-10), called “the section of the way,” is framed by two healings of blind men. At the beginning of the section, we find the progressive healing of the blind man from Bethsaida (8:22-26), which immediately precedes Peter’s profession of faith at Caesarea Philippi. In that case, an unnamed blind man is brought to Jesus by some friends who intercede for him. At the end of the section, we find the healing of another blind man, Bartimaeus, who takes the initiative to ask, crying out—despite the opposition of the crowd—for the grace to regain his sight.

This story holds great symbolic value: Bartimaeus is a reflection of the disciple. In recent Sundays, Mark has guided us through the apostles’ journey. In this process of formation and awareness of the demands of discipleship, the disciple feels blind. Bartimaeus symbolizes the disciple who sits along the road, unable to continue. He represents each of us. Indeed, all of us realize we are spiritually blind when it comes to following Jesus on the way of the cross. Like Bartimaeus, we ask the Lord to be healed of the blindness that paralyzes us.

2. Bartimaeus, our brother: a “master” of prayer

Bartimaeus knows exactly what to ask for, unlike James and John, who “did not know what they were asking for.” He asks for the essential through a simple yet profound prayer: “Son of David, Jesus, have mercy on me!” In this plea, Bartimaeus expresses his faith in Jesus as the Messiah, calling him “Son of David”—he is the only person in the Gospel of Mark to give Him this title. At the same time, he shows a relationship of trust, intimacy, and tenderness, calling Jesus by name and addressing Him as “Rabbuni,” meaning “my teacher.” This title appears only twice in the Gospels: here and in the story of Mary Magdalene, on the morning of Easter (John 20:16).

Life is born from light and develops through light. The same happens in spiritual life: without inner light, our spiritual life is swallowed by darkness. At times, we experience the joy of light, while at other times, darkness seems to invade our existence. Problems, suffering, difficulties, and weaknesses cloud our vision of life, making us unable to follow the Lord. In such moments, Bartimaeus’ prayer comes to our aid: “Rabbuni, let me see again!” Bartimaeus is a master of simple, essential, and trusting prayer!

3. Companions of Bartimaeus: beggars for light

In the ancient Church, baptism was called “illumination.” This illumination, which has snatched us from the darkness of death, is constantly under threat. Our baptism implies a continuous journey of seeking the light. Like the sunflower, the Christian turns each day towards the Sun of Christ. Every morning, while we wash our physical eyes, our soul in prayer rushes to wash itself in the pool of Siloam of our baptism, like the blind man born blind mentioned by John in chapter 9 of his Gospel. And when we find ourselves blind, let us remember that there is the ointment of the Eucharist. With the hands that have received the Luminous Body of Christ, we can touch our eyes and face, mindful of the experience of the two disciples of Emmaus, whose eyes were opened in the “breaking of the bread.” Not only our eyes, but also our face is destined to shine, like that of Moses (Ex 34:29). Indeed, the face of the Christian reflects the glory of Christ (2 Cor 3:18), thus becoming a witness of the Light, placed on the lampstand of the world.

Fr. Manuel João Pereira Correia, MCCJ

The blind man who became able to see

A commentary on Mk 10, 46-52

On his way up to Jerusalem, Jesus arrived at Jerico, a town with a long history in Israel. In this town, Mark places an interesting dialogue, quite different in nature from de one He had with the sons of Zebedee that we read last Sunday.

While the sons of Zebedee put up the question of power and their ranking as followers of Jesus (showing how little they had understood), the son of Timeo, Bartimeo, stands before de “son of David” as he really is: a blind man who wishes to see, somebody who has lost the meaning and feels lost in life.

Let us not forget that, in Marks’s intention, the son of Timeo, as the sons of the Zebedee, real persons as they might be, are brought here, to this story, as personalities that represent all of us, disciples of any time, who search for la light that sometimes we confuse with the glimpses of money, power, prestige or any other blinkering reality.

Let us stop a bit on this story and the dialogue between Bartimeo and Jesus, bearing in mind that somehow we are also taking part in it:

1. At the road side, out of the town. Bartimeo was seating at the road’s side, marginalized from social life, unable to be among the human community.

Do we know in our experience such people as Bartimeo, people marginalized, not taken into consideration, despised because of a physical defect or otherwise? Remember that in our Christian communities there should not be any one discriminated.

But it may happen that we are the marginalized ones; it may happen that ourselves suffer despise in our own family, in the working place…or we may experience problems that seem bigger than what we can cope with. In that case, we should remain in contemplation of this Bartimeo and try to follow his steps as “blind” disciples.

2. He shouts: “Son of David, have mercy on mi”. What a marvellous prayer! We all are in need, in one or other moment in life, of mercy, understanding, forgiveness… Only a stupid and false pride can lead us to think that we do not need God’s and our neighbour’s mercy. Bartimeo is teaching us one of the best prayers ever: “Lord, have mercy on me, help me, since I alone cannot overcome my troubles”. It’s a prayer to say with humility but without feeling of shame or false vanity. Somebody has said that never a human being is greater than when he kneels down. The opposite is just lie or hypocrisy.

3. “What do you want me to do for you? To see again”. Physical blindness is a drama, but many blind people show that it’s not the end of the world and that worse than physical blindness y the spiritual one, to which Mark refers in this story; the blindness of so many people unable to understand God’s love, closed up in their own world of self-content and “self-reference”. This is also a precious prayer: “Lord, let me see your light, so that I may understand your love”.

4. Your faith has saved you. The Italian theologian Bruno Forte says: “ Following a suggestive medieval etymology, “to believe (“credere”) means to give your heart (“cor-dare”), to put your heart into the hands of Somebody else… To believe is to trust in Somebody, say “yes” to his call, to put our own life in His hands, so that He is the Unique and true Lord” (B. Forte, Piccola introduzione alla fede, San Paolo, 1992, p. 16).

This faith-communion with the Other One is always healing, because it helps a person to come out of herself, out of her self-centrality and stablish links with other persons; that link becomes a sign and a means to be in touch with Reality ns, in the end, with God, the Reality that is backing all other reality. That link makes us true to ourselves and to other, healing our loneliness and vulnerability.

As I celebrate the Eucharist today, I enter into communion with the Son of David and, as the blind man, I pray: Lord Jesus, have pity on me; make me see and understand your great love, that love that gives colour, truthfulness and sense to what I am an live.

Fr. Antonio Villarino, mccj

Mark 10: 46-52

Choses from and for men

Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa

Jeremiah 31:7-9; Hebrews 5:1-6; Mark 10:46-52

The Gospel passage recounts the cure of the blind man of Jericho, Bartimaeus.

Bartimaeus is someone who does not miss an opportunity. He heard that Jesus was passing by, understood that it was the opportunity of his life and acted swiftly. The reaction of those present — “and many rebuked him, telling him to be silent” — makes evident the unadmitted pretension of the wealthy of all times: That misery remain hidden, that it not show itself, that it not disturb the sight and dreams of those who are well.

The term “blind” has been charged with so many negative meanings that it is right to reserve it, as the tendency is today, to the moral blindness of ignorance and insensitivity. Bartimaeus is not blind; he is only sightless. He sees better with his heart than many of those around him, because he has faith and cherishes hope. More than that, it is this interior vision of faith which also helps him to recover his external vision of things. “Your faith has made you well,” Jesus says to him.

I pause here in the explanation of the Gospel because I am anxious to develop a topic present in this Sunday’s second reading, regarding the figure and role of the priest. It is said of a priest first of all that he is “chosen from among men.” He is not, therefore, an uprooted being or fallen from heaven, but a human being who has behind him a family and a history like everyone else.

“Chosen from among men” also means that the priest is made of the same fabric as any other human creature: with the emotions, struggles, doubts and weaknesses of everybody else. Scripture sees in this a benefit for other men, not a motive for scandal. In this way, in fact, the priest will be more ready to have compassion, as he is also cloaked in weakness.

Chosen from among men, the priest is moreover “appointed to act on behalf of men,” that is, given back to them, placed at their service — a service that affects man’s most profound dimension, his eternal destiny.

St. Paul summarizes the priestly ministry with a phrase: “This is how one should regard us, as servants of Christ and stewards of the mysteries of God” (1 Corinthians 4:1). This does not mean that the priest is indifferent to the needs — including human — of people, but that he is also concerned with these with a spirit that is different from that of sociologists and politicians. Often the parish is the strongest point of aggregation, including social, in the life of a country or district.

We have sketched the positive vision of the priest’s figure. We know that it is not always so. Every now and then the news reminds us that another reality also exists, made of weakness and infidelity — of this reality the Church can do no more than ask forgiveness.

But there is a truth that must be recalled for a certain consolation of the people. As man, the priest can err, but the gestures he carries out as priest, at the altar or in the confessional, are not invalid or ineffective because of it. The people are not deprived of God’s grace because of the unworthiness of the priest. It is Christ who baptizes, celebrates, forgives; the priest is only the instrument.

I like to recall in this connection, the words uttered before dying by the country priest of Georges Bernanos: “All is grace.”

Even the misery of his alcoholism seems to him to be a grace, because it has made him more merciful toward people. God is not that concerned that his representatives on earth be perfect, but that they be merciful.

[Translation by ZENIT]