Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

Friday, June 16, 2023

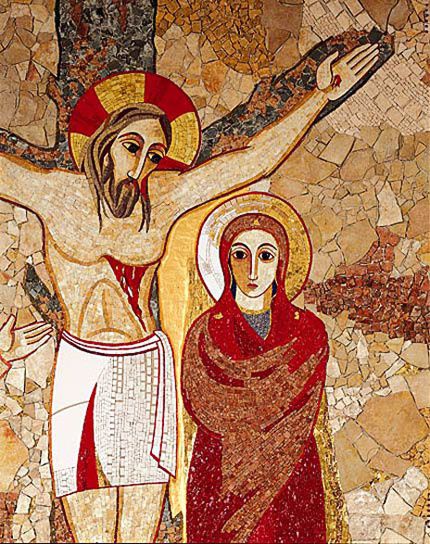

The very form of the Cross, extending out into the four winds, always told the ancient Church that the Cross means solidarity: its outstretched arms would gladly embrace the universe. According to the Didache, the Cross is semeion epektaseos, a “sign of expansion”, and only God himself can have such a wide reach: “On the Cross God stretched out his hands to encompass the bounds of the universe” (Cyril of Jerusalem).

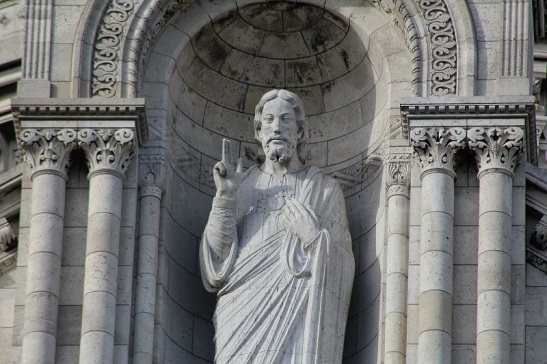

THE HEART

OF THE WORLD

by Hans Urs von Balthasar

“In his suffering God stretched out his arms and embraced the world, thus prefiguring the coming of a people which would, from East to West, gather under his wings” (Lactantius). “O blessed Wood on which God was stretched out!” (Sibylline Oracles).

But God can do this only as a man, and his form is different from that of the animals in that “he can stand up straight and spread out his hands” (Justin). And thus it is that he can reach out to the two peoples, represented by the two thieves, and tear down the wall of division (Athanasius). Even in its outward form the Cross is all-inclusive.

But its interior inclusiveness is shown by the opened Heart, out of which the last drops of Jesus’ substance are poured: blood and water, the sacraments of the Church. Both Biblically and philosophically (in the total human context, that is), the heart is conceived to be the real center of spiritual and corporeal man, and, by analogy, it is also seen as the very center of God as he opens himself up to man (I Sam. 13, 14).

In the Old Testament, the heart is still largely understood as the seat of spiritual energy and of thought, while the bosom or “bowels” (as in “bowels of mercy”: rachamim, splanchna) are rather taken to be the seat of the affections.

In the New Testament, however, both aspects coincide with the concept of “heart”. Having one’s “whole heart” turned to God means the opening of the whole man towards him (Acts 8,37; Mt. 22,37). Thus, the heart that was hardened (Mk.10,5, following numerous parallels in the Old Testament) must be renewed: from a stony heart it must become a heart of flesh (Ez. 11,19, etc.; cf 2 Cor. 3,3).

In the wake of Homer, Greek philosophy saw in the heart the center of psychic and spiritual life: for Stoicism, the heart is the seat of the hegemonikon, the guiding faculty in man. Going beyond this, New Testament theology adds, on the one hand, an incarnational element. The soul is wholly incarnate in the heart, and, in the heart, the body wholly becomes the medium for the expression of the soul.

At the same time, the New Testament adds an element of personhood: it is first in Christianity that the entire man – body and soul – becomes a unique person through God’s call and, with his heart, orients towards God this uniqueness that is his.

The narrative of the piercing with the spear and of the outpouring of blood and water should be read as being continuous with the Johannine symbolism of water, spirit and blood, to which also belong the references to “thirst”.

Earthly water again makes thirsty, but Jesus’ water quenches thirst forever (4,13f). “Let whoever is thirsty come to me and drink as one believing in me” (7,37f); thus the believer’s thirst is quenched forever (6,35). Related to this is the extraordinary promise that, in him who drinks it, Jesus’ water would become a fountain leaping up to life eternal (4,14), which is supported by the verse of Scripture: “Streams of living water will spring from his belly” (koilia: 7, 38).

It is at the moment when Jesus suffers the most absolute thirst that he dissolves, to become an eternal fountain. That verse may refer to the ever-present analogy between water and word/spirit (Jesus’ words are “spirit and life”). Even better, it may be related to the “fountain” in Ezechiel’s new temple (Ez. 47; cf Zach. 13,1), with which Jesus compared his own body (2,2t).

In the context of John’s general symbolism, there can be no doubt that in the outpouring of blood and water the evangelist saw the institution of the sacraments of eucharist and baptism (cf Cana: 2, lff.; the unity of water and spirit: 3,5; and of water, spirit and blood; 1 Jn. 5,6, with explicit reference to “Jesus Christ: “he it is that has come by water and blood”).

The opening of the Heart is the handing over of what is most intimate and personal for the use of all. All may enter the open, emptied space. Moreover, official proof had to be provided that the separation of flesh and blood had been realized to the full as a prerequisite for the form of the eucharistic meal. Both the (new) temple and the newly opened fountain where all may drink point to community. The surrendered Body is the locus where the new covenant is established, where the new community assembles. It is at once space, altar, sacrifice, meal, the community and its spirit.

Love Must Be Perceived

by Hans Urs von Balthasar

In Hans Urs von Balthasar’s masterwork, The Glory of the Lord, the great theologian used the term “theological aesthetic” to describe what he believed to the most accurate method of interpreting the concept of divine love, as opposed to approaches founded on historical or scientific grounds. In the newly translated Love Alone Is Credible, von Balthasar delves deeper into this exploration of what love means, what makes the divine love of God, and how we must become lovers of God in the footsteps of saints like Francis de Sales, John of the Cross and Therese of Lisieux.

This excerpt from Love Alone Is Credible is chapter 5, “Love Must Be Perceived.”

If God wishes to reveal the love that he harbors for the world, this love has to be something that the world can recognize, in spite of, or in fact in, its being wholly other. The inner reality of love can be recognized only by love. In order for a selfish beloved to understand the selfless love of a lover (not only as something he can use, which happens to serve better than other things, but rather as what it truly is), he must already have some glimmer of love, some initial sense of what it is.

Similarly, a person who contemplates a great work of art has to have a gift – whether inborn or acquired through training – to be able to perceive and assess its beauty, to distinguish it from mediocre art or kitsch. This preparation of the subject, which raises him up to the revealed object and tunes him to it, is for the individual person the disposition we could call the threefold unity of faith, hope, and love, a disposition that must already be present at least in an inchoative way in the very first genuine encounter. And it can be thus present because the love of God, which is of course grace, necessarily includes in itself its own conditions of recognizability and therefore brings this possibility with it and communicates it.

After a mother has smiled at her child for many days and weeks, she finally receives her child’s smile in response. She has awakened love in the heart of her child, and as the child awakens to love, it also awakens to knowledge: the initially empty-sense impressions gather meaningfully around the core of the Thou. Knowledge (with its whole complex of intuition and concept) comes into play, because the play of love has already begun beforehand, initiated by the mother, the transcendent. God interprets himself to man as love in the same way: he radiates love, which kindles the light of love in the heart of man, and it is precisely this light that allows man to perceive this, the absolute Love: “For it is the God who said, ‘Let light shine out of darkness’, who has shown in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Christ” (2 Cor 4:6).

In this face, the primal foundation of being smiles at us as a mother and as a father. Insofar as we are his creatures, the seed of love lies dormant within us as the image of God (imago). But just as no child can be awakened to love without being loved, so too no human heart can come to an understanding of God without the free gift of his grace – in the image of his Son.

Prior to an individual’s encounter with the love of God at a particular time in history, however, there has to be another, more fundamental and archetypal encounter, which belongs to the conditions of possibility of the appearance of divine love to man. There has to be an encounter, in which the unilateral movement of God’s love toward man is understood as such and that means also appropriately received and answered. If man’s response were not suited to the love offered, then it would not in fact be revealed (for, this love cannot be revealed merely ontologically, but must be revealed at the same time in a spiritual and conscious way).

But if God could not take this response for granted from the outset, by including it within the unilateral movement of his grace toward man, then the relationship would be bilateral from the first, which would imply a reduction back into the anthropological schema. The Holy Scriptures, taken in isolation, cannot provide the word of response, because the letter kills when it is separated from the spirit, and the letter’s inner spirit is God’s word and not man’s answer. Rather, it can be only the living response of love from a human spirit, as it is accomplished in man through God’s loving grace: the response of the “Bride”, who in grace calls out, “Come!” (Rev 22:17) and, “Let it be to me according to your word” (Lk 1:38), who “carries within the seed of God” and therefore “does not sin” (1 Jn 3:9), but “kept all of these things, pondering them in her heart” (Lk 2:19, 51). She, the pure one, is “placed, blameless and glorious” (Eph 5:26-27; 2 Cor 11:2) before him, by the blood of God’s love, as the “handmaid” (Lk 1:38), as the “lowly servant” (Lk 1:48), and thus as the paradigm of the loving faith that accepts all things (Lk 1:45; 11:28) and “looks to him in reverent modesty, submissive before him” (Eph 5:24, 33; Col 3:18).

Had the love that God poured out into the darkness of non-love not itself generated this womb (Mary was pre-redeemed by the grace of the Cross; in other words, she is the first fruit of God’s self-outpouring into the night of vanity), then this love would never have penetrated the night and it would never in fact have had the capacity to do so (as a serious reading of Luther’s justus-et-peccator theology illuminates in this regard). To the contrary, an original and creaturely act of letting this be done (fiat) has to correspond to this divine event, a bridal fiat to the Bridegroom. But the bride must receive herself purely from the Bridegroom ([kecharitoméne] Lk 1:28); she must be “brought forward” and “prepared” by him and for him ([paristánai] 2 Cor 11:2; Eph 5:27) [1] and therefore at his exclusive disposal, offered up to him (as it is expressed in the word [paristánai]; cf. the “presentation” in the temple, Lk 2:22 and Rom 6:13f; 12:1; Col 1:22, 28).

This originally justified relationship of love (because it does justice to the reality) in itself threads together in a single knot all the conditions for man’s perception of divine love: (1) the Church as the spotless Bride in her core; (2) Mary, the Mother-Bride, as the locus, at the heart of the Church, where the fiat of the response and reception is real; (3) the Bible, which as spirit (-witness) can be nothing other than the Word of God bound together in an indissoluble unity with the response of faith.

A “critical” study of this Word as a human, historical document will therefore necessarily run up against the reciprocal, nuptial relationship of word and faith in the witness of the Scripture. The “hermeneutical circle” justifies the formal correctness of the word even before the truth of the content is proven. But it can, and must, be shown that, in the relationship of this faith to this Word, the content of the Word consists in faith, understood as the handmaid’s fiat to the mystery of the outpouring of divine love. But insofar as the Word of Scripture belongs to the Bride-Church, since she gives articulation to the Word that comes alive in her, then (4) the Bride and Mother, who is the archetype of faith, must proclaim this Word, in a living way, to the individual as the living Word of God; and the function of preaching (as a “holy and serving office”), like the Church herself and even the Word of Scripture, must be implanted by the revelation of God himself, as an answer to that revelation, as it is illuminated by the relationship between the Church and the Bible.

To be sure, the response of faith to revelation, which God grants to the creature he chooses and moves with his love, occurs in such a way that it is truly the creature that provides the response, with its own nature and its natural powers of love. But this occurs only in grace, that is, by virtue of God’s original gift of a loving response that is adequate to God’s loving Word. And therefore, the creature responds in connection with, and “under the protective mantle” of, the fiat that the Bride-Mother, Mary-Ecclesia, utters in an archetypal fashion, once and for all. [2]

It is not necessary to measure the full scope of the faith achieved in human simplicity and in veiled consciousness in the chamber at Nazareth and in the collegium of the apostles. For the unseen seed that was planted here needed the dimensions of the spirit or intellect to germinate: dimensions that, once again, stand out in a fundamental and archetypal way in the Word of Scripture, but which first unfold in the contemplation of the biblical tradition over the course of centuries –“written on the tables of our hearts” and henceforth “to be known and read by all men” (2 Cor 3:2-3), written “in persuasive demonstrations of spirit and power”, spirit as power and power as spirit (1 Cor 2:4). That which the “Spirit” of God, however, interprets in our hearts with “power” (and which the Church interprets in “service to the Spirit” [2 Cor 3:8]) is nothing other than God’s own outpouring of love in Christ; indeed, the Spirit is the outpouring of the Son of God, “the Spirit of the Lord” (2 Cor 3:18), since the Lord himself “is Spirit” (2 Cor 3:17).

When Christ is immediately thereafter designated the “Image of God” (2 Cor 4:4), then this expression ought not to be reduced to mythical terms, since myth was definitively left behind with the dimension of the Incarnation of the Word, which surpassed it. He is the “Image”, which is not a merely natural or symbolic expression, but a Word, a free self-communication, and precisely therefore a Word that is always already (in the grace of the Word) heard, understood, and taken in, otherwise, there would be no revelation. There is no such thing as a “dialogical image”, except that which exists at the higher level of the Word, although it remains true – and contrary to what Protestant and existential theology may claim – that the Word preserves and elevates in itself all the value of the image at the higher level of freedom. If the Word made man is originally a dialogical Word (and not merely in a second moment), then it becomes clear that even the level of the unilateral (ethical-religious) teaching of knowledge has been surpassed.

It is not possible that Christ could have written books (“about” something, whether about himself, about God, or about his teaching); the book “about” him must concern the trans-action between him and the man whom he has encountered, addressed, and redeemed in love. This means that the level on which his Holy Spirit expresses himself (in the letter), must necessarily itself be “in the spirit” (of the love of revelation and the love of faith), in order to be “objective” at all. To put it another way, the site from which love can be observed and generated cannot itself lie outside of love (in the “pure logicity” of so-called science); it can lie only there, where the matter itself lies – namely, in the drama of love. No exegesis can dispense with this fundamental principle to the extent that it wishes to do justice to its subject matter.

Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-1988)

From “Love Alone Is Credible »

Footnotes:

[1] ThWNT, 5:835-40.

[2] Augustine offers a magnificent description of the archetypal prius, of the perfect Yes in the Confessions (XII, 15; PL 32, 833): “Do you deny that there is a sublime created realm cleaving with such pure love to the true and truly eternal God that, though not coeternal with him, it never detaches itself from him and slips away into the changes and successiveness of time, but rests in utterly authentic contemplation of him alone?… We do not find that time existed before this created realm, for ‘wisdom was created before everything’ (Eccles. [Sir] 1:4). Obviously this does not mean your wisdom, our God, father of the created wisdom… [but] that which is created, an intellectual nature which is light from contemplation of the light. But just as there is a difference between light which illuminates and that which is illuminated, so also there is an equivalent difference between the wisdom which creates and that which is created, as also between the justice which justifies and the justice created by justification… So there was a wisdom created before all things which is a created thing, the rational and intellectual mind of your pure city, our ‘mother which is above and is free’ (Gal 4:26)…. O House full of light and beauty! … During my wandering may my longing be for you! I ask him who made you that he will also make me his property in you, since he also made me” (Confessions, trans. Henry Chadwick [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991; reissued as an Oxford World’s Classics paperback 1998], 255-56).

[Combonianum]

A Heart Like His

Fr. Thomas D. Williams, LC

I don’t know about you, but I get a little squeamish when it comes to devotion to “body parts.” Relics are one thing, but “body parts” are another. Living in Italy for many years, I have gotten somewhat accustomed to the practice, but one’s initial uneasiness never disappears altogether.

Here in Rome, for instance, at the church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva we have the incorrupt body of St. Catherine of Siena. Well, most of her body, that is, since her head was removed and sent back to her native Siena, along with a finger, for display at the church of St. Dominic. We also have St. Francis Xavier’s right forearm, though the rest of him is apparently exhibited in the Basilica of Bom Jesus in Goa, India. Across town, we have the Capuchin Church of the Immaculate Conception, familiarly known as the “Bone Church,” since the crypt below it is entirely decorated in the bones of deceased Capuchins. The list goes on and on…

Relics or realities?

So isn’t there something strange about us modern men and women in the twenty-first century reading a book about devotion to the “Sacred Heart” of Jesus? At worst, isn’t this just more worship of “body parts,” and at best, isn’t it a quaint scrap of dusty piety left over from our great-grandparents’ day? Shouldn’t we be moving on to something a little more trendy, a little more hip, and a little less “earthy”? Odd as it may seem, devotion to the Sacred Heart is not just some back-alley practice for the macabre-minded. Nor is it an outdated vestige of medieval piety to be quietly brushed under the rug. It was none other than Pope Benedict XVI who recently said that devotion to the Sacred Heart “has an irreplaceable importance for our faith and for our life in love.”[1]

In explaining this devotion, Pope John Paul II similarly made clear that the Heart of Christ is not just a physical organ, like the pancreas or the gallbladder. When we speak of the heart, he said, we refer to “our whole being, all that is within each one of us.”

The heart represents “all that forms us from within, in the depths of our being. All that makes up our entire humanity, our whole person in its spiritual and physical dimension.”[2]

Unlike the head (symbol of rational thought and calculation) or the belly (symbol of visceral desire), the human heart represents the seat of principles, decisions, convictions, yearnings, commitments, aspirations, and love. Devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, then, means devotion to Jesus himself, to the Word made flesh, to the humanity of the Son of God, and, in a particular way, to the love of God in human form.

Knowing about Jesus or knowing Jesus?

Knowing Jesus Christ means more than knowing when and where he lived, or what he said and did. It means getting to know him more intimately by penetrating into his heart. Knowing him, in turn, leads to loving him, to entering into a friendship with him, and that leads to imitation. But imitating Jesus likewise means more than outward mimicking of his actions. It means allowing the Holy Spirit to make our hearts more like his.[3]

That, in short, is the whole point of this devotion. The simple meditations I offer in this volume are meant to help Christians in this endeavor: to know Christ more intimately, to love him more profoundly, and to imitate him more perfectly.[4]

As a standard for our own behavior, we often ask: What would Jesus do? This is a key question, but I can’t help thinking that many times, our answer reflects “what I would do if I were Jesus,” rather than “what Jesus would do if he were in my place.” Why is this? Surely it’s not ill will – it must rather be from ignorance. We simply don’t know Jesus as well as we should.

Becoming like Jesus means becoming more human and more holy. What is holiness after all except union with God, a union that passes through the humanity of Christ and perfects our own humanity? The Second Vatican Council reminded us that Christ “reveals man to man himself… He who is ‘the image of the invisible God’ is himself the perfect man.” Moreover, “by his incarnation, the Son of God has united Himself in some fashion with every man. He worked with human hands, he thought with a human mind, acted by human choice, and loved with a human heart.”[5]

If we want to know who we are, who we were created to be, we will find the answer in Jesus Christ and especially in his heart. This is a down-to-earth devotion, not based on esoteric practices or special techniques, but on contemplation of Jesus Christ, who reveals God to us and reveals our true selves as well.

Giving God a chance to change our hearts

Union with Christ is not just the result of hard work either. We grow more and more like Christ by cooperating with his grace in our lives.[6] In order to grow in faith and love we Christians need to experience the love of Christ. We need to see it, feel it, grasp it, be overwhelmed by it, immerse ourselves in it. Only the intense experience of being unconditionally loved – by none other than God himself – can enable us to love him and others as we yearn to.

St. John wrote that love consists in this, “not that we have loved God, but that he has loved us” (1 Jn 4:10). We need, in Pope John Paul’s words, to penetrate the heart of Christ.[7] And as Pope Benedict recently wrote, it is by deepening our relationship with the heart of Jesus that “we will be able to understand better what it means to know God’s love in Jesus Christ, to experience him, keeping our gaze fixed on him to the point that we live entirely on the experience of his love, so that we can subsequently witness to it to others.”[8]

In the following pages, then, I will offer thirty meditations, one for each day of the month of June, the month traditionally dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. I also include two extra meditations to be used on the feasts of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Immaculate Heart of Mary respectively. Each meditation will focus on one particular aspect or virtue of the heart of Christ, as seen in the Gospel. I would hope to offer as comprehensive a view as possible of the many facets of his heart, so that at month-end we will know, love, and imitate him a little better. For some the book may serve as a short daily reading, as something to think about and reflect on during the day. For others, it will provide material for a period of prayer, to meditate on Jesus’ love and converse with him in the depths of your heart.

Our goal, as I have said, is to know Jesus so as to love him and then imitate him. Day after day, our prayer will be: Lord, let me know you so well that I cannot help but love you. Let me love you so deeply that I cannot help but want to be like you. Make my heart more like yours!

Endnotes:

[1] Letter of Pope Benedict XVI, To the Most Reverend Father Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, S.J, May 15, 2006. [2] Pope John Paul II, Homily at Abbotsford Airport (Vancouver), Tuesday, September 18, 1984. [3]“ Following Christ is not an outward imitation, since it touches man at the very depths of his being. Being a follower of Christ means becoming conformed to him who became a servant even to giving himself on the Cross. Christ dwells by faith in the heart of the believer, and thus the disciple is conformed to the Lord. This is the effect of grace, of the active presence of the Holy Spirit in us” (Pope John Paul II, encyclical letter Veritatis Splendor, no. 21). [4] “Is not a summary of all our religion and, moreover, a guide to a more perfect life contained in this one devotion [to the Sacred Heart]? Indeed, it more easily leads our minds to know Christ the Lord intimately and more effectively turns our hearts to love Him more ardently and to imitate Him more perfectly”(Pope Pius XI, encyclical letter Miserentissimus Redemptor, May 8, 1928, AAS XX, 1928, p. 167). [5] Second Vatican Council, Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World Gaudium et Spes, no. 22. [6] To imitate and live out the love of Christ is not possible for man by his own strength alone. He becomes capable of this love only by virtue of a gift received. (VS 22) [7] “No one can truly know Jesus Christ well without penetrating his Heart, that is, the inmost depths of his divine and human Person” (Pope John Paul II, Angelus message, June 20, 2004). [8] Letter of Pope Benedict XVI, To the Most Reverend Father Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, S.J, May 15, 2006.

http://www.catholiceducation.org/articles/religion/re0984.htm