Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

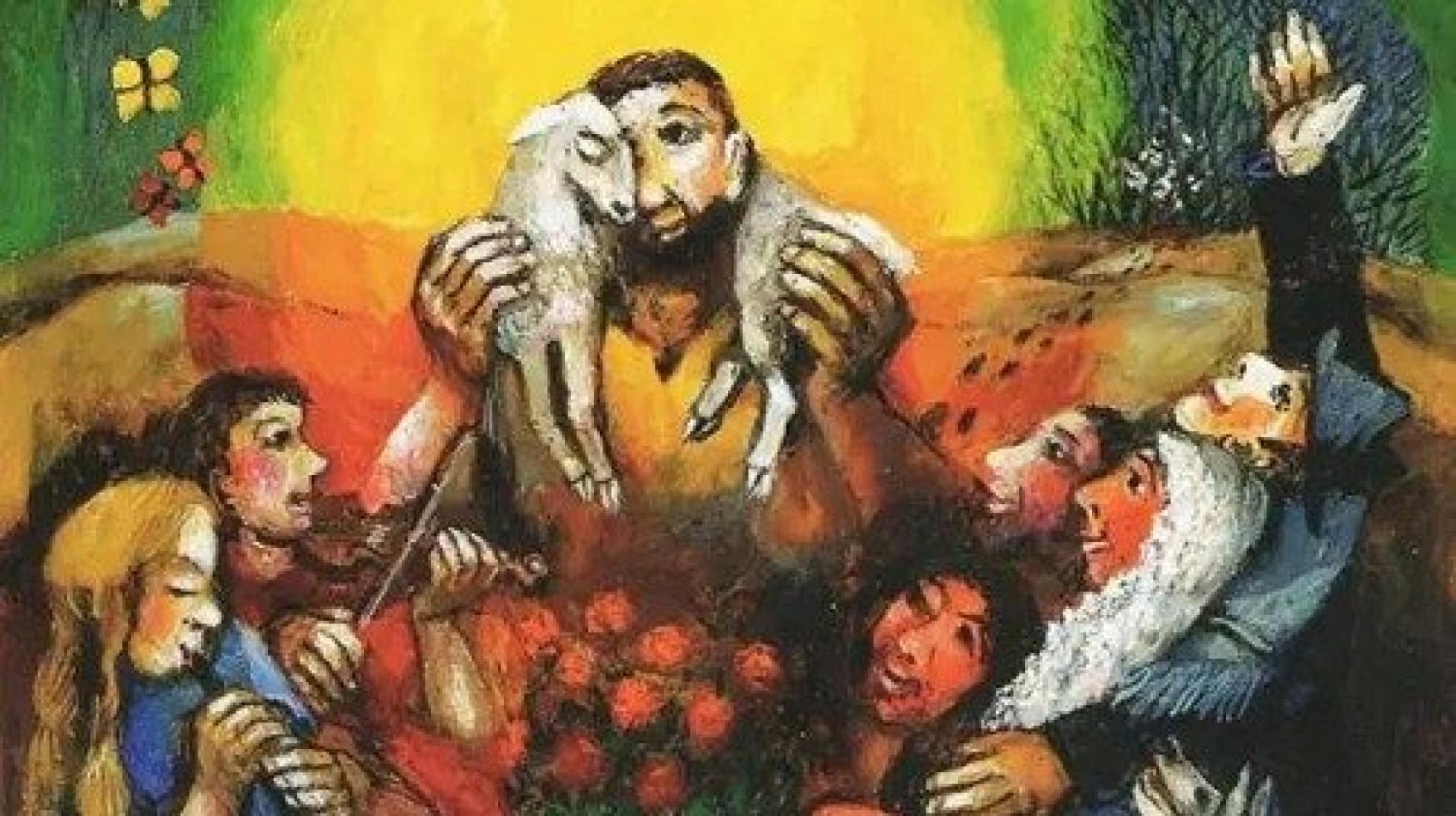

The Fourth Sunday of Easter is called Good Shepherd Sunday because, in each of the three years of the liturgical cycle, a passage of chapter 10 of John’s Gospel is proposed. Today, the first part of this chapter is reported (vv. 1-10) where the theme of Jesus the Good Shepherd is not developed but only hinted at. The central image, in fact, is that of the door. Further on, in his long discourse to the Jews, Jesus proclaims: “I am the good shepherd” (v. 11). Today, he presents himself twice as the door (v. 7). [...]

John 10:1-10

Good Shepherd Sunday

GOSPEL REFLECTION

The Fourth Sunday of Easter is called Good Shepherd Sunday because, in each of the three years of the liturgical cycle, a passage of chapter 10 of John’s Gospel is proposed. Today, the first part of this chapter is reported (vv. 1-10) where the theme of Jesus the Good Shepherd is not developed but only hinted at. The central image, in fact, is that of the door. Further on, in his long discourse to the Jews, Jesus proclaims: “I am the good shepherd” (v. 11). Today, he presents himself twice as the door (v. 7). To this image, others are added: the fence, the thieves and robbers, the guardian and strangers. Who are they? Whom do they represent? What is the meaning of the “similitude”?

Let’s assume an explanatory note about the customs of the Palestinian shepherds.

The sheepfold was a pen surrounded by stone walls on which were placed bundles of thorns. Brambles are allowed to grow on it to prevent sheep from exiting and thieves from entering. The pen could be in front of a house, built outdoors, or on the slope of a mountain. In the latter case it was typically used by most shepherds who bring their sheep at night; one of them was awake while others slept.

To say—as Luke does in the story of the birth of Jesus (Lk 2:8)—that those who stood guard “watched” is not entirely accurate. In fact, armed with a stick, he was positioned at the entrance of the fold—that had no door. He squatted and, in that position, blocking the access, he himself became “the door.” Typically, he dozed off, but his presence was enough to deter the raiders from approaching the fold and to prevent the wolves from getting into the enclosure. The sheep could be approached only by whoever he allowed to pass.

In the morning, when every shepherd stood at the door, the sheep immediately recognize his step and voice. They get up and followed him, sure to be carried out in the pastures of fresh herbs and oasis with pure and abundant water. They followed him because they felt loved and protected; the shepherd had never disappointed nor betrayed them.

From this experience of his people’s life, Jesus sets a parable that is not immediately clear: enigmatic images accumulate and overlap, and the Jews did not understand what he was saying to them (v. 6).

Let us begin by dividing it into two parts.

In the first part (vv. 1-6) the figure of the true shepherd is introduced. The beginning of the speech is rather abrupt and provocative. It contains mysterious allusions to dangers, enemies, attackers: “Anyone who does not enter the sheepfold by the gate but climbs in some other way, is a thief and a robber” (v. 1). Then the true shepherd enters the scene. The feature that sets him apart is tenderness: he knows his sheep by name; and calls them “one by one.”

For Jesus, anonymous masses do not exist. He takes interest in each of his disciples. He pays attention to the gifts, strengths, and weaknesses of each. He joyfully contemplates the young and agile kids. They frolic and run forward but his thoughtfulness, his attention goes to the weakest of the herd: “He carries the lambs in his bosom, gently leading those that are with young” (Is 40:11). He understands their difficulties, does not force the issues nor impose unsustainable rhythms but evaluates the condition of each, helps and respects.

In contrast to this shepherd, the thieves and bandits appear. Who are they? How can they be recognized? To whom does Jesus refer them to?

In his time there were “shepherds.” There were religious and political leaders posing as attentive guides of the people’s welfare but in reality, they were seeking only their own interests. Their goals were domination, personal prestige, exploitation: their methods were violence and lies.

They were not authentic shepherds. So one day, before the crowd, Jesus was moved with compassion “because they were like sheep without a shepherd.” He led them out, made them lay “on green grass” and distributed to them in abundance the bread and the nourishment of his word (Mk 6:34-44).

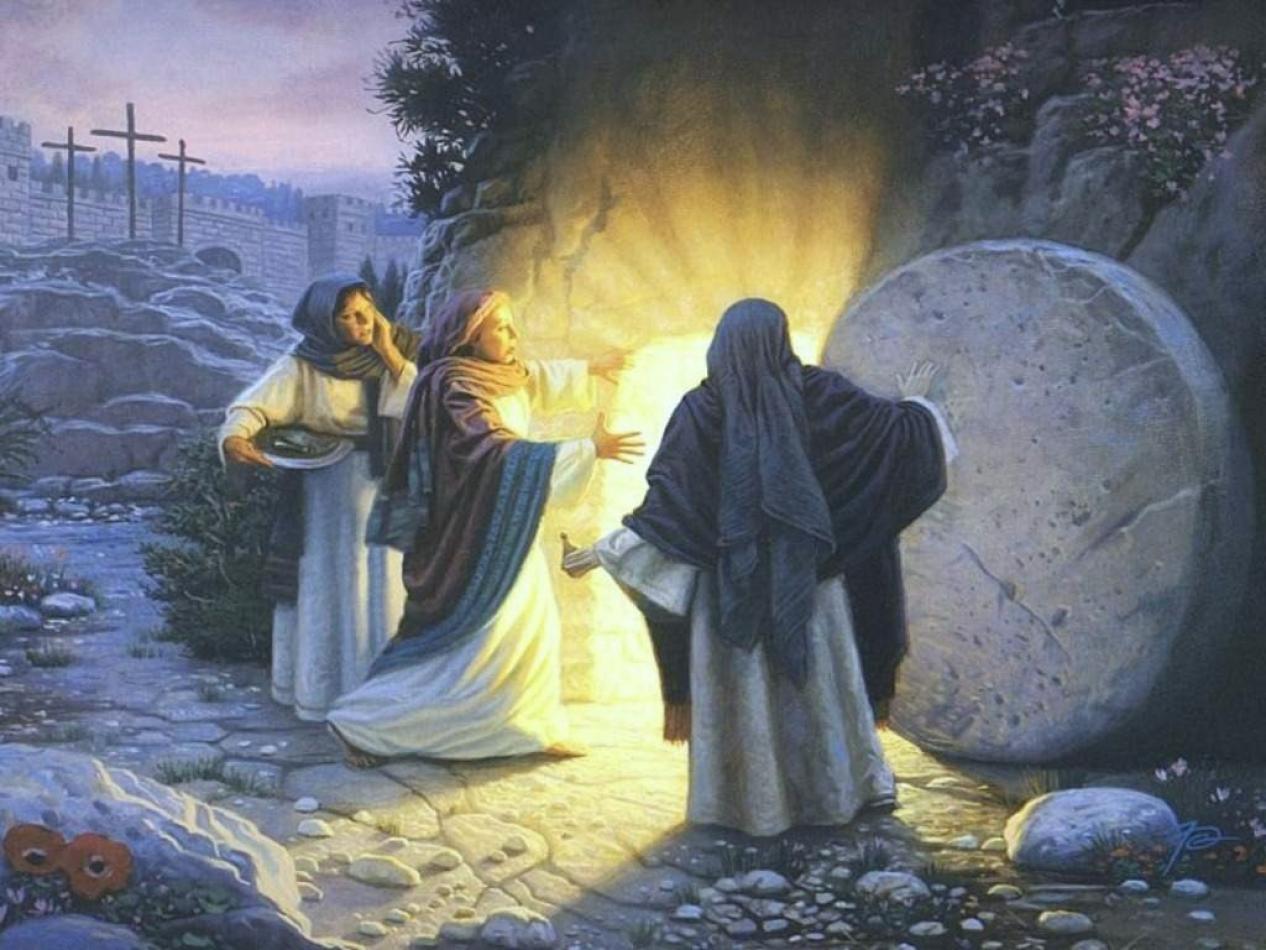

Note, in this first part of the Gospel, the insistence on the “voice of the shepherd” that is “heard” (v. 3), “recognized” (v. 4) and immediately distinguished from that of the strangers’ (v. 5). Even after the resurrection, Jesus will be recognized for his voice.

The eyes of the disciples will be misled: He will be taken as a wayfarer, a ghost (Lk 24:15,37), a fisherman (Jn 21:4); but those who heard him could not be mistaken. His voice was unmistakable.

Today this voice continues to resound, crisp and alive in the Word of the Gospel. It is the only one that sounds familiar to the disciple. The others that overlap, though strong and insistent, are not familiar to him.

Whoever is “taught by the Spirit” is able to discern the voice of the shepherd, in the midst of the noise of so many other items. He flees when he hears the steps of thieves and robbers: the impostors who come just to drag him in the paths of death.

In the second part of the passage (vv. 7-10), Jesus appears first as “the gate of the sheep” then as “the gate.” If one keeps in mind the explanation given above, we could say that he is the guardian that is placed at the entry like “gateway.”

The door has a dual function: to let the owners pass and to prevent the entrance of outsiders. These are two functions that are developed, in many allegories, by Jesus.

He is the one who decides who can have access to the sheep and who has to stay away from the flock (vv. 7-8). The one who has assimilated his own feelings and provisions in respect of the sheep, who is willing to give his life as he did, can pass and is recognized as a true shepherd. The thieves and bandits are those who came before him (v. 8). He was certainly not referring to the prophets and the righteous of the Old Testament.

Thieves were the religious and political leaders of his time who exploited, oppressed and caused all sorts of sufferings to the people.

Bandits were revolutionaries who wanted to build a freer and more just society: they cultivated noble ideals but resorted to wrong methods. They fomented hatred for the enemy, preached the use of violence and proposed the use of weapons. The one who acts in this way does not have the same feelings and the same dispositions as Jesus: he does not pass through the door.

In the last verse (v. 10) this opposition is taken up. In a dramatic crescendo, the work of the thief is described: he steals, kills, and destroys. Three verbs that summarize the work of death. Anyone who approaches a man to take his life is “a thief;” he is on the side of evil; he is a “son of the devil” who “was a murderer from the beginning” (Jn 8:44).

The action of the shepherd is antithetical: he comes to bring life and life in abundance.

Through the door, not only shepherds pass but the sheep also enter and exit. Jesus presents himself as the gate also in this sense (v. 9). Only the one who passes through him reaches fertile pastures, finds the “bread that satisfies” (Jn 6) and “water welling up to eternal life” (Jn 4), thus obtaining salvation.

Jesus is a narrow gate (Mt 7:14) because he asks for self-denial, selfless love to others, but it’s the only one that leads to life: all the others are traps, pitfalls which precipitate in abysses of death: “Broad is the gate that leads to destruction and many go that way” (Mt 7:13).

Fernando Armellini

Italian missionary and biblical scholar

https://sundaycommentaries.wordpress.com