Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

Monday, October 8, 2018

Unique, amazing, overwhelming. And let’s admit it straight away: off-the-pegs clothes didn’t suit him. Pointless to get involved in cutting and sewing... he’d have suffocated in them. He was as he was. That’s how he was made. Every size was too tight on him. And there was nothing to do if the pattern didn’t fit.

“The omnipotence of prayer is our strength”

Thus Daniele Comboni, the apostle of Africa, writes in his letters. From his correspondence the traits of a surprizingly free man, entirely faithful to the Church, emerge…

«The saints and scoundrels have fought me. But the works of God must be fought. And I am more cheerful than ever, and strong as death». «God remedies my blunders with his grace».

Unique, amazing, overwhelming. And let’s admit it straight away: off-the-pegs clothes didn’t suit him. Pointless to get involved in cutting and sewing… he’d have suffocated in them. He was as he was. That’s how he was made. Every size was too tight on him. And there was nothing to do if the pattern didn’t fit. And Pius IX himself understood immediately, and still didn’t hesitate to place full trust in him by giving him the mission of the vicariate of Khartoum in central Africa; and his biographers also know it well, for despite their efforts to describe him, they’ve always found themselves trying to cover his illimitable figure with paper. «Limitlessly faithful to the Church», they’ve said, «but also capable of living his limitless fidelity with a similarly limitless freedom». «Men like him are contemporaries of the future», wrote Jean Guitton. Yes, indeed. Because Daniele Comboni, or rather, Saint Daniele Comboni, the apostle of Africa, truly belongs among the ranks of great souls who never stop unsettling and involving, disarming and fascinating.

It’s enough to look into his letters to get an idea and encounter him face to face, with no screen. Because right there, in his correspondence, one finds all of Comboni. In the flesh. Genuine. With his cheerful, strong and human temperament, his outsize individuality that was at the same time quite remote from any cult of personality, the great insights and daring courage, his determination and his despairs, his consumate diplomacy and his disarming purity.

The volume containing The writings numbers over 2,200 pages. Nine hundred letters are reproduced. And it should be made clear that in comparison to what he wrote it’s little enough. He himself, writing to the Bishop of Verona, Cardinal Luigi di Canossa, 21 May 1871, assured the recipient that from the start of the year up to then he had written 1,347 letters, and two years later he confides: «I have more than 900 letters to write. So many the relations with distinguished benefactors that I need to cultivate…». This monumental correspondence, written almost always by robbing the time from sleep, written on whatever came to hand, under the scorching sun of the desert or in huts sodden with rain, is precious evidence of an inexhaustible passion, of a life wholly consumed in the mission for the salvation «of unfortunate negritude», a task in which he was a pioneer, in advance of his times. «I have nothing in my heart except the sole and pure well-being of the Church and for the health of these souls I would give a hundred lives if I had them,» he writes, «and certainly, with slow sure steps, walking on eggshells, I shall manage to begin stably and set up the work conceived by the regeneration of negritude, that everyone has abandoned, and that is the most difficult and arduous task in the Catholic apostolate».

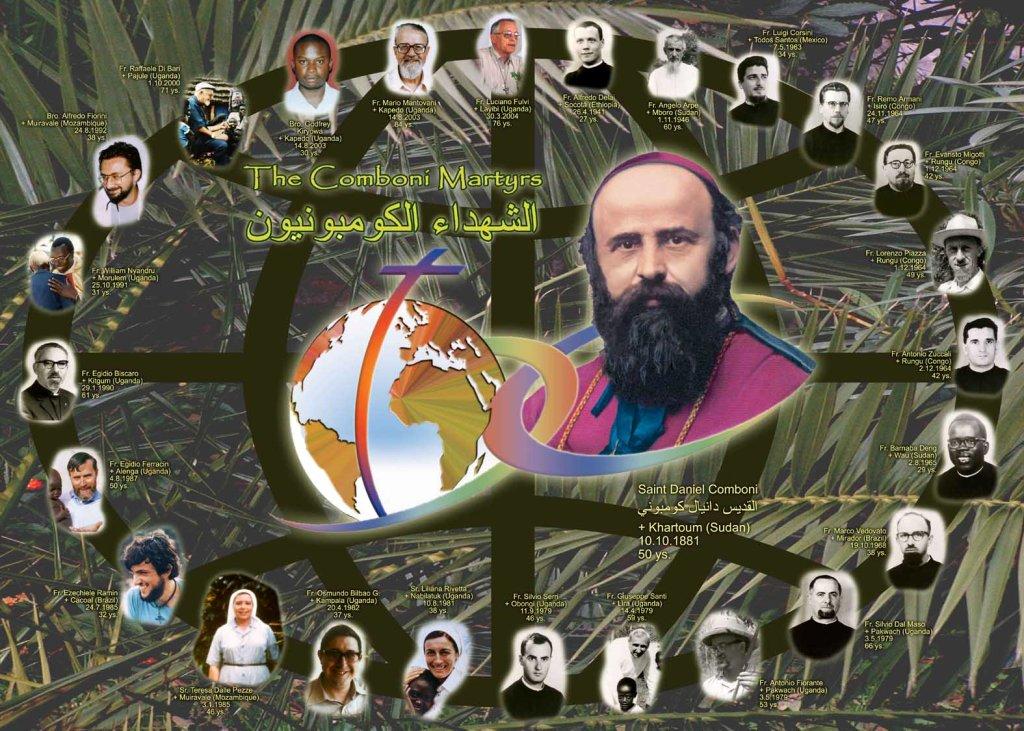

«Between me and the Lord God we are all»

The “Plan to regenerate Africa with Africa” he had jotted down in a flash after praying at the tomb of Peter. It was 15 September 1864 and five later years he subjected it with determination to the Fathers of Vatican Council I. For some it was folly. But he was first to succeed in setting up stable mission posts in those places, opening the way to the evangelization of the continent; he was also the first who, with long-sightedness and unimaginable daring for the time, succeeded not only in bringing consecrated women into Africa, with the clear insight that it was «impossible to find a place among those peoples» without them but, in the conviction that the mission could not be the «business of priests and nuns» only, in encouraging ordinary believers to follow him. From when, in 1858, he made his first trip to Africa till his death in 1881 at fifty, he undertook another seven journeys into the heart of the Black Continent. To give account of all his vicissitudes, struggles, dangers, without counting the privations and the killing fevers, is an enterprise as arduous as his work, and the letters attest the endless variety of contacts and relations that he managed to establish for his missionary purposes. He opened exchanges and contacts with the greatest Africa experts and explorers of the time, himself venturing into the thick of a thousand dangers and adversities, where nobody ever had dared go before, drawing maps and drafting reports on the customs and habits of then unknown peoples with meticulous precision. He made known the life conditions, the famines and pestilences of those places.

He met the men of government and the potentates of half Europe: from the Emperor Napoleon III to Leopold II of Belgium and Franz Josef, harnessing attention, energies and funding. He made contact with all the larger missionary orders. He set up relations with the missionary associations of the whole of Europe and with the most authoritative ecclesiastics of the continent. Travelling on the slave routes, he harshly denounced the ignoble traffic to the potentates of Europe, working for the ransom and education of slaves, and he didn’t hesitate, given his political realism and broad views, to make friends with Turkish and Egyptian leaders, the great pashas and muftis of those Arabized places, and to make contact with even the most bloodthirsty slavers. «

The features of a good beater and trafficker are three: prudence, patience, impudence,» he wrote: «the first I lack: but by golly don’t I make up splendidly with the other two, and above all with the third». In a letter to Count Guido di Carpegna, who did not lack financial means, he affirmed in words that startle the reader: «I’ve been 17 days in Paris. Here I consult and study the great Institutions to get the work on the right footing…; but if God set hand to it it’ll get done; if God doesn’t set hand to it, neither Napoleon III, nor the most powerful kings, nor the wisest philosophers on earth will ever be able to do anything. So let God do it; and then I the lowest of the sons of the men will succeed. Between me and you we are rich, between me and Saint Francis Xavier we are saints, between me and Napoleon III we are powerful, between me and the Lord God is everything». As if to say: what one lacks, the other has in abundance, and the figures come out right…

«If we pray everything is accomplished because Christ is a gentleman»

The subtle humor and «evangelical “nonchalance”» that enabled him to speak candidly and if need be «lambast» people, at times harshly, even when his words were addressed to eminent churchmen, certainly didn’t save him from misunderstandings, campaigns of defamation, obstacles and fierce calumnies. «They have accused me to Propaganda [Fide] of being guilty of all seven of the deadly sins and of having sinned against all the ten commandments in the Decalogue and the Precepts of the Church, even more… I, a negative quantity, deserve worse than that because I am a sinner and have debts to pay to God…», he told Father Sembianti.

But to the Cardinal Prefect of Propaganda Fide, Alessandro Barnabò, to whom he never failed even in the most difficult moments to show his unconditional obedience, he wrote as follows in 1876: «Your Eminence will see that even in this new storm, the enemy of human salvation has tried do me ill and to put obstacles in the way of the Work that belongs to God; and you will understand that the storms that oppress me are many, that it will be a miracle if I’ll be able to bear up under the weight of so many crosses. But I feel so full of strength and courage and trust in God and in the Blessed Virgin Mary, that I’m sure to overcome everything, and to prepare myself for other bigger crosses in the future. … And it is with the Cross for dear “spouse” and most wise teacher of prudence and sagacity, with Mary my dearest “Mother”, and with Jesus my “all”, I do not fear, O Eminent Prince, either the tempests from Rome, or the storms from Egypt, or the disturbances from Verona, or the clouds from Lyons and Paris».

And if his judgment on himself in the letters comes out in these definitions: «Harlequin pretending to be prince», «dishwasher of the work of God», «useless little chocolate soldier», «sinful cobbler», «feckless priestling», he also confided again to Father Sembianti: «One has to suffer great things for the love of Jesus Christ… fight with the potentates, with the Turk, the atheists, the Freemasons, the barbarians, the elements, the monks, the priests… but with his Grace we shall triumph over the Pashas, the Freemasons, the atheist governments, the cockeyed thoughts of good people, the tricks of the bad, the snares of the world and of hell… all our trust is in him who died and rose for us and chooses the frailest means to do his work».

He repeats «trust», hundreds of times. And it is a leitmotif that leaps to the eyes in the correspondence of this boundless life. An unshakable, limitless trust. A total trustful abandonment that enabled him to hope against each hope, with invincible steadfastness, in the face of the most terrible and catastrophic events, grievous above all in the last years of his life. He had consecrated Africa to the Sacred Heart of Jesus and to the Sacred Heart of Mary Queen of Negritude and set himself to knocking on the doors of the convents of half Europe to ask for the help of their prayers, «to assault the sky with our incessant prayers».

«The omnipotence of prayer is our strength», he wrote from Cairo to Monsignor Luigi di Canossa. «Prayer is the most sure and infallible means. If we pray everything is accomplished because Christ is a gentleman. So my late lamented superior told me as a boy; what I always understood to mean that to the petite, quaerite, pulsate, pronounced and repeated with the due conditions, always coincide, the verbs accipietis, invenietis, and aperietur». To the rector of the Institute of Verona in a moment critical because of material difficulty, in the tone of his unmistakeable style, he wrote: «You must realize that if one really knew and loved Jesus Christ, one would move mountains: and small confidence in God is common to almost all (so long experience tells me) good souls and also devoted to much prayer, which have a lot of confidence in God on their lips and in words, but little or none when God puts them to the test, and sometimes lets them lack what they need… And if there is somebody here who has real faith and trust in the on-high, more than you, more than me, and more than the saints in Europe (at least than very many) it is Sister Teresa Grigolini, Sister Vittoria… Therefore pray and have faith, pray not with words, but with the fire of charity… I tell you this to advise you to have steadfast and resolute trust in God, in Our Lady and in Saint Joseph». And the letters contain some very singular aspects and expressions of his particular devotion to Saint Joseph.

Saint Joseph and the temporal graces

In 1870, in the course of the Vatican Council I, Pius IX proclaimed Saint Joseph patron of the universal Church. Comboni gave him a special task by entrusting him with the protection of Negritude and making him confidential administrator and steward of the mission. He wrote: «Time and disasters pass, we become old; but Saint Joseph is always young, is always good-hearted and his head is always steady, and he always loves his Jesus, and concerns himself with his glory, and the conversion of central Africa is always of lively concern to the glory of Jesus». And for Comboni this was not only a pious consideration but factual reality: «How can one doubt divine Providence and that of the watchful steward Saint Joseph, who has never failed to help me and who in only eight and a half years, and in such calamitous and difficult times, sent me more than a million francs for founding and setting up the work in Verona, in Egypt and in the interior of Africa? The monetary and material means for the upkeep of the Mission are the last thing in my thoughts. It’s enough to pray…», he wrote to Cardinal Alessandro Franchi in June 1876.

His relationship with Saint Joseph was marked by the most amazing familiarity, made of pressing invocations, trust, but also pleas, complaints, admonishments and even blackmail. He describes him as «Gentleman», indeed «King of gentlemen», «master of the house», «steward of much judgment and good heart», «arbiter of the treasures of heaven», «pillar of the Church»; «and though everything be overwhelmed he will always remain: triumpher over all the cataclysms in the universe». With uninhibited trust he calls him Joe, Joey, Little Joe, Little Joey. «Everything comes out of the beard of the Eternal Father by way of Little Joey, and we’ll make Little Joey jump…».

The terrible famine of 1878 was a very hard strain on the finances of the mission, but it in no way harmed trust in the heavenly steward. «I have exhausted all my resources to support all the missions and I’ve found over a thousand francs of debts. For a long time expenses have tripled though Moslems and Pashas help the mission. Let Your Eminence be certain», he wrote from Khartoum to Cardinal Giovanni Simeoni, «that Saint Joseph the steward of central Africa will make everything good within a year, and will support the mission. He has never allowed me to go bankrupt and he has pulled me out of it so many times, do you think he will leave me embroiled now? Within a year he’ll make the balance-sheet level. Not the level balance-sheet resoundingly promised a hundred times by the Minghettis, by the Lanzas, by the Sellas, by the De Pretis and the others at the Italian trough… The best of my missionaries share my hopes, my certainty, my faith. I shall send you regular reports of them… If I live».

But sometimes Saint Joseph seemed deaf and lazy. He didn’t hesitate to remind him of his duties, because, he states, «one has to be a bit daring with this blessed saint», who however «never disappoints even if he has an exact scale of values: he thinks first of the spirit and our souls and then of money». In a letter written less than a year before his death he lets it be known that he has run into financial trouble: «May there be no more bankers in the world, were they even the saints of heaven. The only banker (and his bank is safer than all the banks of the Rothschilds), in whom my trust has remained, is my dear heavenly steward, to whom I have recommended the business of getting a good subsidy from Propaganda; indeed I’ve chased the holy and good steward Saint Joseph into a corner to get me help from Propaganda. If Little Joey won’t listen to me, I’ve threatened to turn to his wife; and having made a good novena (ordering it for my nuns) for the Immaculate Conception, and the three-day prayers to the Ispettazione del Parto, do you think he’ll say no? I’m certain that he’ll hear me; my Joe Steward must have a bit of self-respect and make sure we don’t go running to women in money troubles, which is men’s business…».

In the last years of his life, trials, persecutions, abandonments, continual death among his best loved collaborators, «bitter pills» and more obstacles and calumnies coming from Church circles, gave him no respite: «I find myself here on the battlefield in danger of losing my life at every instant for Jesus and for these poor souls and I am oppressed and sunk in an ocean of tribulations and adversities that are rending my soul. My health is broken: the fever won’t leave me…». «Have courage. Do not fear», he wrote again in his last letter. «May everything God wills come about. God never abandons those who trust in him. I’m happy…». On the evening of 10 October 1881, consumed by fever, on a soaking mattress, Comboni went into his death throes. Bending over him Father Bouchard said: «Monsignor, the supreme moment has arrived…». «He fixed his eyes on the crucifix and kissed the cross with tenderness…».

As Péguy wrote: «All the slave subjugation of the world disgusts me, says God, and I would give everything/ for a free man’s look,/ for a free man’s fair obedience and tenderness and devotion».

[Stefania Falasca – in Combonianum]