Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

Friday, May 29, 2015

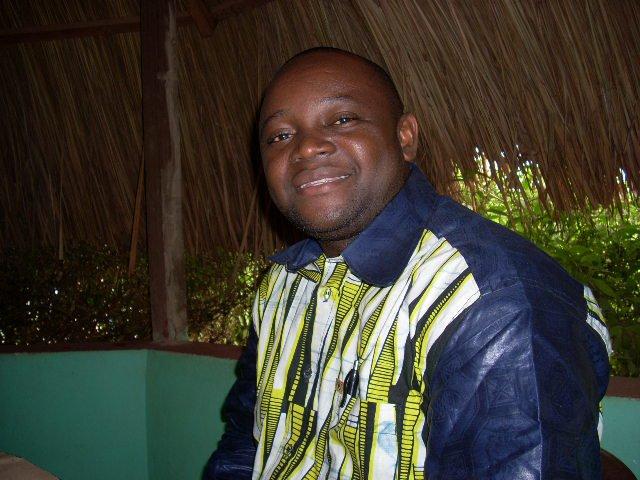

This is the third goal for the Year of Consecrated Life proposed by Pope Francis. In its accompanying letter, the General Council explains what this goal consists in, for us Comboni Missionaries: “to be signs and witnesses among the peoples and outskirts where we are sent, living in a radical way our religious and missionary consecration”. I have been asked to share my experience – not a long one – and my reflection on this third part: the glance of hope. [Fr. Léonard Ndjadi Ndjate, mccj, in the picture].

Starting point:

personal experience of God

In my brief experience as a young consecrated person (13 years with vows) and a Comboni Missionary, it is clearly apparent that the starting point, upon which the confident glance and the courage of hope are founded, develop and are purified, is the experience of God. When contact with the Word of God, nourished by the daily Eucharist, brings to birth in me a life of prayer that is simple but true and profound, I gradually discover that the Father is the source of all hope, that the Son is its most beautiful manifestation and that the Holy Spirit ensures its vitality and fecundity. If, however, this experience is either lacking or weak, I feel uneasy and without the motivation to embrace the future with faith and freedom. It is precisely this that Pope Francis affirms in his letter to all consecrated persons: “The hope of which we speak is not based on numbers or works but on Him in whom we have placed our confidence and for whom ‘nothing is impossible’ (Lk 1, 37)”. “This – the Holy Father continues – is the hope that does not disappoint us and that will allow the consecrated life to write a great history in the future”. To put it briefly, the grace of looking to the future with confidence and courage depends upon my encounter with the person of Christ.

Fr. Günther Hofmann,

in South Africa.

What hope is not

The consecrated person is called, by nature and by vocation, to go out of themselves and to face the call to continual conversion. This truth carries with it a twofold requirement: to be oneself and to be capable of openness. Today, this attitude allows us to avoid seeing the future as the proximate end to a life lived in mediocrity and to avoid that sort of realism that is based on concrete facts such as “fewer vocations, ageing personnel, economic difficulties, rapid social changes, the challenges of internationality and globalisation, the consequences of relativism and the fragility of the youth”, and seems to affirm that nothing more can be changed and that we must accept things as they are. For us young people, this realism is basically no more than a disguised form of defeatism with which we do not agree. Looking to the future does not mean seeking that which the consecrated life ought to be in order to have a better future. To do so would be tantamount to maintaining a formal, sometimes nostalgic, lifestyle that might become the final court of appeal for present choices. One would tend, therefore, to judge the present operative choices by the criteria of the past. Because of this, religious life is in danger of becoming sheer boredom with its future being reduced to a second-hand carbon copy of the present, created with the methodology of the past.

Neither does thinking of the future of religious life imply the development of an argument that is detached or pessimistic or, still less, a display of enthusiastic optimism. Hope is not acquired by an excess of prudence and the desire for the perfect reorganisation of consecrated life to “control better one’s missionary future”. In itself, a position like this, however valid, could have a reductive effect on the possibilities and new things that the Spirit raises up today. It is necessary to be daring with Christ. Experience has often shown that those who lack the courage to risk their lives end up, with the passing of time, repeating themselves, and, as a result, are impoverished. To pretend to create hope with these attitudes would result in legitimising healthy mediocrity and, above all, in preventing new impulses of the charism from responding to the present challenges of the mission. As young people, we feel the need to leave some room for the Holy Spirit to discover space for liberty and the new that are still to be found in consecrated life and the Comboni charism. Our “certainties” must not prevent us from seeing far and wide.

Fr. Filomeno Ceja,

in Guatemala.

Some room for the Holy Spirit

In the prayer for the Chapter, we invoke the “Holy Spirit, source and strength of the mission, who urges us to share our lives that all may have life”. To speak in this way of the Holy Spirit seems to me to be a reminder and an awareness of his presence and action in rendering credible the witness of the consecrated. It means making some room for him. Giving space to the Spirit involves, basically, accepting the newness of the charism in the present context. Planning and discernment in view of the reformulation of our structures must not neglect the spaces of liberty in which the Spirit causes something new to be born, in harmony with the charism. The Spirit, in fact, gives us the courage to engage ourselves in the mission with creativity. Without concealing our real difficulties, we feel the urgency of listening to the Spirit so that he may lead us to new places of work by way of new paths. We are convinced that the consecrated missionary life is not linear. Some methodologies and policies must give way. Our vision of the future, as young people, is not put in the usual terms of optimism or pessimism since we are trying to live out our consecration as a call to a lively and continual conversion. It is a call to change in fidelity to the Gospel and to the charism. It is not important that some changes seem to be the logical consequences of decisions born from the discernment of the Institute. What is important is to continue to believe in the power of the Spirit in each of us: the young, the old, the active, the sick or those in difficulty. The more we believe in him and the more we leave room for him, the more he works and transforms, enlightens and inspires us so that we may wake up the world, witnessing before it the goodness of God. Our looking to the future is by way of being humble and repositioning ourselves where the Spirit wishes to lead us. This openness to the Spirit becomes tangible witness when we show we are willing to “let go”, or “to move”. This process may well be kenotic but it is liberating. In this spiritual openness, the first step consists in listening to the Word of God so as to calm every fear.

Comboni Missionaries,

in Brazil.

Listening to the Word of God to calm our fears

There are situations in which fear may kill even before death comes. Indeed, thinking of the future, the problems and challenges of consecrated life today create fear. This is because they not only render the mission more complex but also obscure the reasons for hope, and so prevent us from looking to the future with faith and serenity. To these problems, Pope Benedict XVI adds the increase of violence, the fear of others, wars and conflicts, and the racist and xenophobic attitudes that still hold sway in the world of human relations (AM 12).

In making an analysis of the youth, the previous General Chapter noted that they are exposed to “the dangers of hedonism, relativism, consumerism and secularism. They therefore avoid complex situations, tiresome and demanding relationships and long-term responsibilities. They are the victims of the society in which they live”. Consequently, we see in basic formation “defections, mediocrity and weakness of motivation, inconsistency, an imbalance between ideals and life that show how educational praxis has not yet found that effectiveness that the formative process was meant to inspire and guide” (AC ’09, 74,77). I myself, while in youth pastoral work, have noted, besides great weakness in the process of psycho-affective maturity, a pseudo-mentality based on the struggle for subjective identity that leads to the mentality of the eternal provisional nature of things, giving importance to what is ephemeral and marginal and weakening the true sense of belonging. It is this fact that forms the basis of a phenomenon present in the majority of the youth: the loss of identity in a stable body. This, unfortunately, gives rise to a low degree of availability and the lack of zeal and commitment.

In this case, how can we not fear for the future? Doubts may arise and realism must make us recognise how much these facts will affect, in the future, the choices of the religious life, of the mission and also of the formation that should ensure it. However, if, on the one hand, these difficulties cause great uncertainties as regards the future, on the other, it is precisely in the heart of these uncertainties that our hope becomes incarnate. The fear of going out into a future so different from what we have seen up to now is calmed and minimised by means of trust in the Lord to whom we have given our lives. His words are reassuring: “Do not be afraid… I am with you until the end of time” (Jr 1, 8; Mt 28, 20).

The Lord is calling us to trust him. Our living or our dying depends upon our trust in God. Fundamentally, it is a call to faith. If, inside ourselves, we are illuminated by the Word and by his Person, we may look forward in peace and serenity to the future of consecrated life. We can still dare to hope and to love. This penetrating look and the courage to dream of a beautiful and fascinating mission are still possible. What we must do is to “let go” and surrender to the Word (Ac 20, 32); we must entrust ourselves to the Word and let ourselves be led by it because it is powerful, possesses energy and is a living reality in action (Heb 4, 12).

The more trust in the Lord and in his Word warms our hearts, the more our steps become sure and the more we can look to the future with confidence and proclaim with Comboni “I foresee a happy future for Africa”. Yes, it is only confidence in the Master who calls (Jn 1, 35) that can give birth to hope in the midst of uncertainty.

Fr. Joseph Mumbere,

in Congo.

The potential of the youth

In his message, the Pope suggests the right attitude to reduce this fear. It consists in “staying awake and vigilant”.

Concretely, this is a matter of a lifestyle that requires care and attention to ourselves, our own interior lives, our own physical and mental health, our own ongoing formation, the quality of our interpersonal relationships and the way we communicate and collaborate to offer to the mission the best of ourselves. This is because the mission cannot live off crumbs. Our ability to stay awake and be vigilant depends upon the quality of our ties with Christ the “Light”. In this surge of reawakening and vigilance, consecrated life needs the freshness and potential of the youth. With the dynamism, the vitality and the freedom that distinguish us, we young consecrated people can offer a determining contribution to the mission. As young people, we bring with us a dual joy: the joy of youth and the joy of consecration. This joy is already a sign of hope. A happy young missionary is a sign of hope for the mission. The youth, whose hearts are aflame with missionary passion become, for the Church and the world, a ray of hope.

Our joy is incisive in the present but also decisive for the future since it brings us to make the gift of ourselves to the mission. It is a joy which creates sensitivity and a mentality of flexibility and openness, of friendship and camaraderie, of politeness and humour, of courage and group spirit, of availability and creativity, of missionary effort even to the point of martyrdom, where necessary. It is therefore my responsibility, as a young consecrated person, to cultivate this joy in such a way that it infects fraternal life, my relationships and my encounters, the mission and the poorest. Thus, these words of Pope Francis truly resound: “Where there are consecrated people, there is joy”. Nevertheless, the dynamism typical of the youth has an indispensable need: the wisdom of the elders.

Fr. Efrem Agostini (92 years)

and Fr. Víctor Alejandro Mejía Domínguez.

The wisdom of the elders

In African tradition, the elders are the repository and witnesses of tradition as well as the transmission belt for it. The experience, wisdom and witness of the elders are necessary to educate the youth in preparing the future because they help to keep our enthusiasm within the real dimensions of the mission and our initiatives. I have had the grace of living my first years of mission alongside an older confrere. I admired him very much, and learned from his calm, his wisdom and the richness of his missionary experience. He lived through everything with discretion. And so we made beautiful, visible, liveable and pleasant our community life and our missionary presence in the parish. Our community provided an atmosphere of serenity that, first of all, was good for us and also for visiting confreres and for the faithful of the parish: “See how they love each other”. This alliance between two generations, two mentalities and two different cultures made our missionary service fruitful. Today, I thank God for having placed that confrere on my path; the journey was not without its contrasts and misunderstandings. We built it up with patience, truth and love. I mention this simply because it is possible to make our life beautiful. The reality of different cultures, instead of being an obstacle, can be lived as a gift for the journey that we must travel with patience, truth and mutual acceptance. Thus, we can embrace the future with hope. In this interaction, Pope Francis invites us young people to be, first of all, protagonists of the dialogue with the generation that comes before us. In this way – the Pope says – we can work out together new ways of living the Gospel and responding more fully to the demands of witness and proclamation”. My modest experience obliges me to say that we have two obstacles to face.

Two obstacles

The obstacles to both this generational dialogue and this alliance are the experimental mentality and the butterfly syndrome. In practice, the first consists in exaggerating one’s own missionary experience, presenting it as a victory over dangers, sufferings and instability. One is like the survivor of a catastrophe or a battle, a hero. One recounts the most difficult part of the mission and ends with: I never gave up; therefore I am an expert in mission.

In this way, the mission is presented not as something beautiful, exciting and fascinating but more like a drama. The fact of having overcome makes one an expert. One often hears: he has missionary experience! Or: so-and-so is an expert. Well, sometimes we may forget that being expert depends on human resources: available means, calculations, age, duration and scientific competence. The experimental mentality makes missionaries experts but not witnesses. It culminates and becomes a real obstacle to hope when it blocks the dynamism of the growth of the younger generations on the pretext of inexperience. In African society, this obstacle stops all progress and makes the community sterile since it is the enemy of what is new and of any change whatever. Is it, perhaps, present in consecrated life?

The second obstacle is that which we may describe as that of the “butterfly”. It derives from the knowledge that one has achieved the autonomy necessary to guide one’s religious life personally, wiping the slate clean of everything. It makes us live in the illusion of having definitively arrived. It becomes a mechanism of stopping one’s ears and creates a certain hostility to and rejection of one’s own ongoing formation, of spiritual accompaniment, of confession and of listening to the wisdom of the elders. In stubbornly defending the autonomy and development of the person, this obstacle makes us ignore the dimension of kenosis and leads to the rejection of the difficult mission but sometimes opening the door to a crisis with authority. It is a spirit of pseudo-self-sufficiency and disorder. It is an attitude that leads us to live with no real passion. It reaches an explosive level when it contaminates the spiritual dimension, thus developing hostility towards all that concerns the interior life. One no longer lives one’s consecration but goes about like a butterfly. Why? Simply because the unifying centre of our lives – a close relationship with Jesus Christ – has been lost. This obstacle impoverishes our humanity but above all our spiritual life as it deprives us of humility and of docility, two virtues that are necessary, that we need in order to learn the secret joys of the consecrated life. Is this attitude also present in us? How can we overcome these two obstacles? I wish to indicate two ways: flexibility and fidelity.

Fr. Fabrizio Colombo,

in Italy.

Flexibility and fidelity

As young people, we are witnesses to the birth of a new era. The world is changing, society is progressing, interpersonal relationships are becoming fluid, human mobility is forever increasing, life is digitalised and a new culture, complex and marked by a plurality of modes of being and acting, is being established in the world.

This profound mutation leads us to review some of our certainties. The previous Chapter had already warned us about the fact that “The Comboni Institute is living through a phase of deep and rapid transformation. While enriched by new nationalities and cultures, we also face negative developments, resistance to the “old” and the “new”...The Institute’s face is changing and becoming ever more multicultural, rich and diversified, yet it also requires an extra effort to maintain unity while guaranteeing the transmission and inculturation of the charism” (CA 2009, 3.4).

This new situation presupposes that all should adopt a new mentality: that of flexibility. In practice, for the youth, flexibility does not mean inventing anything new, adapting to or swallowing whole the products of the modern age. Flexibility consists in such a capacity for openness that one can confront, and allow oneself to be challenged by the emerging reality. Flexibility consists in welcoming what is new rather than rejecting it, dialoguing with it rather than ignoring it. As seen by young consecrated people, flexibility consists not only in starting again from Christ but also from the reality that presents itself to us, a reality in transformation that challenges us. If our certainties make us so insensitive that we avoid facing reality, the attitude of flexibility, instead, leads us to welcome whatever is beautiful, true and good that the Lord has hidden in the new reality. We believe, therefore, that the reality, as it presents itself to us, is the bearer of a message of conversion and transformation. The new reality, too, is the place where God waits for us, speaks to us, questions us and makes us grow. It is not a matter of “fusing with or becoming confused with” the wonderful proposals of the modern world but of living in our specific way as an alternative to the proposals of the modern world. From this derives the need to go out, to go to meet people and today’s culture. In the manner of the Visitation.

Keeping a fruitful distance

for a true encounter

As consecrated people, we are in the world but not of the world. This choice does not mean proposing a new orthodoxy or forming part of the counter-culture. As young consecrated people, our desire is to rediscover, through flexibility, our duty of being, at the heart of a new dawning era, a true place of questioning. By the grace of our consecration, we want to raise questions in the hearts of the people of our time. We wish to dialogue with contemporary culture. It seems to me that this fruitful distance constitutes a missionary proposal that is essential for the future of consecrated life. Because it gives life to every true encounter that includes openness, welcoming and encounter. It is interiority that embraces otherness. It means opening oneself to what is being born or spreading, to that which is beautiful or dramatic, good or bad, in order to carry in one’s heart the worries and problems of the world, the woes and joys of our brothers and sisters. And it is there that we will express authentic communion that has its roots in the incarnation, that tells us that the Son of God – for whose sake we are consecrated – is the manifestation that God so loved the world so much (Jn 3,16).

In this way, listening to and accompanying the men and women wounded by life who freely come to us, becomes an attitude and a priority. As it was in Comboni’s time; but we can only do this if “in communicating with others” – the Pope affirms – we possess the openness of heart which makes possible that closeness without which genuine spiritual encounter cannot occur” (EG, 171).

Community of Santarém Novitiate,

in Portugal.

Self-giving and fidelity

Changing reality invites discernment and responsible adhesion on our part. The concrete form of that adhesion is the gift of oneself, a value many young people are capable of today. In a world dominated by a lifestyle based on self-interest and competition, the gift of oneself, which is born of encountering and confronting reality, becomes the place of intensity where Christ calls and explicitly involves each one. The gift of oneself is the place within which each one is mobilised to give quality and fecundity to the mission. The mentality of flexibility creates self-giving. But this flexible spirit, which generates adhesion and self-giving, becomes more true and radical if it springs from fidelity to Christ and the charism. Flexibility is necessary in order to encounter reality but in fidelity to the Gospel and to the charism. Without fidelity to Christ and our charism, flexibility is just improvisation, pure opportunism. It is by starting from fidelity to Christ, his Word and the charism that we may know the sentiments of his Heart with which we can dialogue and witness, announce, denounce and renounce in order to give life in abundance. In this way we can wake up the world. To give life in abundance has its affective echoes and starts with small gestures of politeness, truth and fraternal kindness.

Conclusion

The journey to be travelled in order to embrace the future with hope consists in offering ample room for freedom and creativity so that all may develop their talents. In this way, consecrated life may witness to the riches of God present in the life of every consecrated person.

If, therefore, the foundation of this hope and this joy lies in union with Christ, the faithful friend, its expression lies in the awareness of living radically the gift of consecration. We can embrace the future with hope to the extent that vitality, the gift of God, obscured and now fragile, is freed and empowered to humanise and evangelise the world. Accepting, with flexibility and fidelity, the transformations imposed on us whether by reality, the discernment of our superiors or the action of the Spirit. It is, however, a demanding and painful journey because it makes us experience the fear of being transferred, of being removed or of being the looser.

Viewed in faith by young consecrated people, this fear is baseless since the Spirit continues to work and it is this that is really important. Consecrated life is in transformation. We young people have no desire to be undecided spectators, fearful and complaining. If we acquire a mentality of flexibility and fidelity, we may offer our humanity to wake up the world and nourish it that it may have life in abundance. In the journey to embrace the future with hope, the hermeneutic key that makes communion possible in this inter-cultural situation is Jesus Christ; and St. Daniel Comboni. In them, we, both young and old, meet, find inspiration and set out once again, hand in hand, all facing the same direction, that of the missio Dei. From Christ and from Comboni we may learn that holiness and capability of being today an authentic presence of hope for the future. They both experienced flexibility and fidelity. Let us follow them.

Fr. Léonard Ndjadi Ndjate, mccj