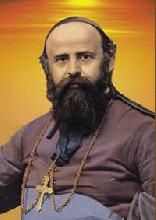

Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

Daniel Comboni witness of holiness and master of mission

“…Holy and capable. One without the other has little value for those who follow an apostolic ca-reer… The missionary has to go to heaven together with the souls which have been saved. So, first of all, holy, that is averse to any sin or offence to God, and humble: but it is not enough: they need charity which will make them capable…” (W 6655)

1. The day of the canonisation of our Founder and Father is drawing near. This is a unique occasion for our Institutes because it also coincides with other important and significant events: the General Chapter of the Comboni Missionaries, the preparation for the General Chapter of the Comboni Missionary Sisters and the General Assembly of the Comboni Secular Institute which took place in July 2003. As General Councils we feel the need to address you by letter which, besides marking this happy occasion, gives us the opportunity to present a few points for reflection on the holiness of Daniel Comboni and on the meaning of his canonisation. We hope that these points will help us during this time of grace. Let us keep in mind that for the Comboni Secular Institute certain concepts contained in the letter such as consecration, community life and Evangelisation are lived according to their specific lay vocation.

2. This moment has been welcomed in our Comboni Family with joy and hope because it is seen as a message from God that has to be read and interpreted. We have heard the feelings and expectations which are being expressed by members of the Comboni Family who are saying that “this is a good time to ‘listen again’ to Comboni; this is an opportunity to reclaim our roots, to reclaim what is essential and what counts: to be holy and capable. This event in both the Universal Church and the Local Church offers us an opportunity to recover a programme of liberation in favour of all those who have been unjustly isolated and forgotten by society. It is a call to personal and commu-nity transformation in accordance with the witness of holiness of our Founder. It is an opportunity to better focus the objectives of our mission ad gentes and a time to revitalise missionary animation in the Churches in which we work...”

3. These requests and expectations might seem excessive if considered in the abstract, but they are more attainable if they are seen in the light of the icon to which from now on our missionary life will be continually referred: Saint Daniel Comboni. He is the companion of our journey, walking alongside us and a multitude of brothers and sisters the Lord continues to send us and with whom we continue to “make common cause”. Such a conviction and the experience of “companionship” will not only open up a new perspective on our life and work, will not only be a consolation and boost, but it will also be binding on us because, with the canonisation of Daniel Comboni, the Church publicly recognises the exemplary life of this son of hers and therefore pronounces a conclusive verdict on the quality of his life, on his coherence and on his actions. Gathered by the Church before our Founder, we now know that we are in front of an authentic “source” of missionary wisdom.

4. What can we gather from this particular moment which the Church grants us? What does it mean to us today that Comboni is a saint? In the post-synodal Exhortation Ecclesia in Africa, John Paul II reminds us that: “A missionary is really such only if he commits himself to the path of holiness […] The new urge towards mission ‘ad gentes’ demands holy missionaries. It is not enough to renew pastoral programmes, nor to better organise and coordinate the ecclesial bodies, nor to explore with deeper perception the biblical and theological bases of faith: what is needed is to awaken a new ‘holy fervour’ among the missionaries and the whole Christian community” (EA 136).

5. The aim of this letter is to give voice to that which Daniel Comboni, by his witness, and the witness of those who lived with him, would want to pass on to us, almost like a viaticum, on the journey of mission. This letter therefore, will offer a few reflections on the kind of witness he gave, on the origin of the mission, on the subject of mission and on the options which are necessary for a creative fidelity to the charism.

6. The canonisation of Comboni establishes an authentic moment of grace for us as the Comboni Family, insofar as it affirms, with the authority that comes from a lived experience, approved by the Church, the necessary link between holiness and the mission ad gentes.

7. A simple statistical observation could help us appreciate the grace of a Founder recognised as being of significance for the whole Church. Of the 476 saints canonised during this pontificate, there are only four Founders of Missionary Institutes. These are Eugenio de Mazenod (1782-1861), Marcellino Giuseppe Benoît Champagnat (1789- 1840), Daniel Comboni (1831-1881) and Arnoldo Janssen (1837-1909). A closer look at their histories shows us that, of the four, only Comboni and Janssen were founders of Institutes that are exclusively missionary. This first annotation, even if in passing, is not without significance. The least we can say is that the canonisation of Daniel Comboni reminds us of a holiness which is strictly connected to the mission ad gentes as an enduring characteristic of the Church.

8. Holiness, or “the perfection of charity” (LG 39), forms the central reality of the Church as “mystery”. She is constantly called to contemplate and incarnate the divine love, which goes out towards humanity and tends, by its very nature, to its full resolution in the great reunion of all in the house of the Father. Nevertheless, the Church cannot do this without our eyes “fixed on Jesus who leads us in our faith and brings it to perfection” (Heb. 12: 2), and without people who, now as in the past, “despise and despised the shame”, “endure and endured the opposition of sinners” and “in the fight against sin… had to keep fighting to the point of bloodshed” (Heb. 12: 3-4). Without the faces of men and women consumed with love, our God would be an invisible God, indifferent to human suffering, a useless God, a distant, invented, virtual God, and the Church would be a community with no memory and no prophecy. Instead the Church will always be made up of a “host of witnesses” (Heb. 12: 1) to urge and encourage those of us who are still running in the race. It is impossible, therefore, to separate the holiness of the Church from the holiness in the Church. Comboni now becomes a tassel of this portrait gallery that transforms the present into “diligent love, example, solidarity, intercession” (LG 51) and “proclamation” (AG 10).

9. The holiness of Comboni continues to call the Church and all of us Comboni Missionaries to our true identity as consecrated men and women for the mission. The person of Comboni and his life, lived as a journey of love without limits, speak to our hearts in a most convincing way and show how holiness and mission are two inseparable realities. In Redemptoris Missio John Paul II reminds us of this: “The call to mission derives, of its nature, from the call to holiness… The universal call to holiness is closely linked to the universal call to mission. Every member of the faithful is called to holiness and to mission. This was the earnest desire of the Council, which hoped to be able ‘to enlighten all people with the brightness of Christ, which gleams over the face of the Church, by preaching the Gospel to every creature’ (cf. Mk. 16: 15)” (RM 90).

10. By his way of life, Comboni seemed to anticipate the fundamental affirmations of Vatican II on the responsibility of the whole Church for the proclamation of the Word and the transformation of the world into the Kingdom of God (LG 17). This unequivocal call of the Council proclaims that the mission is the primary responsibility of the Bishops (LG 23). Comboni had said this almost a hun-dred years before in his Postulatum pro nigris Africae centralis, which was sent to Vatican I in 1870. He drew the attention of the Council Assembly to the collegial responsibility of the Bishops in the face of the mission of the Church, a Church without borders, without barriers, open on all fronts, to everything and everyone. He wrote: “Every effort must be made to unite Africa to the Catholic Church. This, in fact, is required by the honour and glory of Our Lord Jesus Christ, to whose reign, after such a long time, Central Africa is not yet subject even though he shed his blood for its regeneration. This is required also of the ministry entrusted to you whom the Holy Spirit has appointed as Bishops to lead the Church of God” (W 2308).

11. We are called, through the example of our holy Founder, to constantly witness to and remind the Church that reference to the mission ad gentes cannot be either casual or sporadic. It is an inte-gral part of its sacramental structure and it assesses the truth and holiness of the Church of Christ. Of course, today ad gentes cannot be identified solely with geographical movement, but in respond-ing to urgent situations and, in doing so, to contribute to the salvation and transformation of a worldwide society. In his time Comboni made the Church aware of his vision and today he contin-ues to place the missionary message of salvation in Christ at the centre. If we look at the state of humankind: peoples as yet not evangelised, violence, injustice, discrimination, oppression, poverty and intolerable suffering, we will be convinced of the necessity of this mission ad gentes, of the need to proclaim the transforming love of Christ.

12. Let us overcome our hesitation, our fears and our doubts. The holiness of Comboni establishes a renewed call to believe that the Christian mission really is still at the beginning and that this is a testing ground for the Church. “The mission ad gentes faces an enormous task, which is in no way disappearing. Indeed, both from the numerical standpoint of demographic increase and from the socio-cultural standpoint of the appearance of new relationships, contacts and changing situations, the mission seems destined to have ever wider horizons” (RM 35).

13. In his holiness, Daniel Comboni is telling us not only that the mission is ongoing, but also how it must continue. Thus we are drawn to take his holiness as an expression of mission in the form of his person and of his works. Two witnesses confirm the truth of this. Sr. Caterina Chincarini was a 20 year-old Comboni Missionary Sister who travelled with Comboni from Cairo to Khartoum and from El Obeid to Delen in 1881 and was imprisoned by the Mahdi from 1882-1891. At the ordinary process in Khartoum in 1929, she said, “Even when Comboni was alive, we all held the Servant of God to be a saint. Everyone said so. When he arrived in Khartoum as Bishop, the Governor sent a boat just for him. The whole city turned out to meet him and they were all saying: here comes a saint” (P II, p. 1256). Sr. Teresa Grigolini was one of the first five Pie Madri to leave for Africa in 1877 and was also a prisoner of the Mahdi. At the ordinary process in Verona in 1929 she added an interesting observation on the difference between essence and appearance. She said, “Outwardly he did not seem to be a recollected man, but his behaviour made me believe that he was always in the presence of God.” (P II, p.1236)

14. To discovery the meaning of Comboni’s holiness requires an effort; it is important to move from the appearance to the essence. It is important to be able to reach the interior biography in order to understand how his holiness was able to bring about a shift in history from within and, in his case, with the involvement of Church and society, to restore the almost defunct Vicariate of Central Africa.

15. Comboni was a man with one single ideal and was not the superficial enthusiast who gets lost in a thousand unrealistic causes. In spite of his many activities, Comboni had one only cause. How-ever, he did not turn in on himself because the demands of his cause and his plans for the mission of Central Africa were to range over the whole of Africa and of the world. He was one of the few men in the life of the Church who can be identified with one continent. As St. Francis Xavier was the missionary of the Far East, so Comboni cannot be thought of without Africa. He and Africa are inseparable.

16. Comboni was completely dedicated to the work to which he felt called. He was never stubborn or violent. He was never overcome and was a true bulwark and, in spite of his many sufferings, his many letdowns, even his weaknesses of character, he never turned in on himself, was never disap-pointed and never gave up. Wherever there was a failure in the proclamation of the Gospel, wher-ever an injustice to the dignity of a person or of a people, there Daniel Comboni was to be found. His steadfastness and openness was perceived above all by the poor, whenever they came upon him. This was the case with Maria José Oliveira Paixão, the Brazilian woman who, in 1970, at the age of ten, was cured by his intercession. In an interview in 1996, 26 years later, she said, “In the bearded man (barbão) I got to know as a child at the time of my healing I have rediscovered today a man who, during his whole life, fought for the weak and ransomed the blacks so that they could be evan-gelisers to themselves. Mgr. Comboni had great plans for the whole world and he succeeded be-cause his missionaries are present in the whole world and they still follow the Founder today.”

17. There were two-mainstays of his work on which its continuity depended. One was his fidelity and one was his generosity. We see in him a man of great fidelity who never gave in to compromise or relied on his willpower, because he was conscious that his difficult task had come from God. He looked for God and only the ways of God to reach the heart of the African, to reveal it and discover within it the seed of self-regeneration. At the same time he desperately sought the African who was the most abandoned of his time, but he looked for him with the heart of God. Comboni was a gen-erous man in whom everything and everybody was imprinted and this was instantly perceived as total acceptance. Cardinal of Canossa, with a little regret, noted, “That blessed Father Daniel [….] has a heart that feels too much and so he keeps on giving” (P II, p. 1249-59). He was more than a strong man, and no one could doubt his abounding energy. He was a true, honest and sincere man. His heart could be read on his lips and there was nothing hidden, no pretence and nothing complicated in him. The Sisters, who bore with him the “heat of the day” of the African undertaking noted that, “he was very humble, such that sometimes we scolded him” (P II, p. 1255). “He was as simple as a child: as he was sincere, so he thought that everyone was the same. He could never believe that others could use deception or act falsely” (P II, p. 1265).

18. As he was simple of soul, he was determined in all he undertook. He always started from con-crete situations, from flesh and blood people. His conclusions were never the result of a speech or reasoning, but they were always focussed on concrete decisions and working plans. He never gave up. He learned to conjugate mainly one verb: to start again. The love of Christ (cf. 2 Cor. 5: 14) drove him, urged him, pushed him on, held him in its power and taught him the value of small steps and of patience. He often and meaningfully used the expression “by small steps”, day by day. Of course, to advance gradually is not a euphemism, but to walk on thorns. Thus he saw the need to “impress upon the novices that they are to be like lambs led to the slaughter, to embrace great diffi-culties, hardships and sacrifices and to be subjected to a slow martyrdom” (W 5746).

19. In 1865, while in Paris, Comboni learned that he had been expelled from the Mazza Institute; in 1869, Lyons cut his funding and it seemed as if Cardinal Barnabò was turning his back on him fol-lowing an unjustified slander from one of his own. In 1878, Propaganda Fide took the best part of the Vicariate away from him and gave it to Cardinal Lavigerie without consulting him; in 1881 his ability and moral reliability as a Bishop, as a man and as a Founder of his own Institute were put in doubt. His reply was firm, “With the cross… and with Jesus who is my all, I am not afraid… not of the storms of Rome, nor of the tempests of Egypt, nor of the mists of Verona, nor of the clouds of Lyons and Paris. I am certain that by walking slowly and surely on the thorns I will manage to begin steadily to establish the Work which I have devised of the Regeneration of Central Africa, a place which has been abandoned by many” (W 1710). The real novelty is not to begin, but to constantly start again and to persistently carry on without delays.

20. Comboni was constantly starting again throughout his life, but he never abandoned the furrow marked out for him by God and this is why the seed he sowed germinated at the right time. The value of these enduring new beginnings arises from the history of the Vicariate of Central Africa and particularly from the original lists of missionaries who ploughed the mission territories. The verb ‘to start again’ coupled with these names is mixed with the taste of death, of burning desert sand, of dark and putrid water from goatskins, of human skeletons strewn along the caravan routes, of the slave traffic, of sudden fevers, of exhaustion, of journeys with no return, of violent and fatal attacks of black water fever and so on. It is important not to forget that Comboni always started again in dramatic conditions. He went to the mission of Central Africa knowing that from 1847 to 1872 out of 120 missionaries 46 had died and all the others had given up (W 2849-2863). Comboni held out with a vision of the future and with hope when, from 1872, he was given responsibility for the immense Vicariate. At the time of his death, there were 28 graves, including his own, and only 11 survivors among priests, sisters and brothers in the mission of Khartoum. His greatness lies in the fact that he did not wait for better times, but that he forced the times by entrusting them to Providence and to his missionaries.

21. So, was he a hero? No, but simply a man who “kept his eyes fixed on what is invisible” (2 Cor 4: 18), as Paul would say, and he moved forward like Moses, “like someone who could see the invisible” (Heb. 11: 27). He saw the hand of God and the purpose of his undertaking. Thus he was able to perceive the positive aspect of people and of events; and this attitude generated great hope. His own dying words witness to an integrated personality even from a human point of view, in which his depth of being, his plan, the people around him and his surroundings were all in harmony. His hope was born of an interior composure and a sincere faith, “Do not be afraid; I am dying, but my work will not die. There will be much to suffer, but you will see the success of our mission.”

Comboni’s legacy to us expressed in his own words:

“Such a difficult mission as ours… cannot survive on appearances and with egoistic people full of themselves….” (W 6656)

22. Two precise conditions: no liking for outward appearance (it is necessary to go to the essentials) and no seeking of oneself (it is important to always look outside of the self). If we examine this closely we will see that this is the human maturity of an extroverted and positive person who tends to prefer to help the other to grow rather than worry about self. This kind of person is more concerned with God and his Kingdom rather than the search for understanding or approval of per-sonal plans, is more able to be consistently committed to community objectives rather than only to personal ones, and finally, is more inclined to study, understand and be committed in favour of the needs of others rather than claiming personal rights.

23. There were certain unmistakable human qualities in the life of Comboni, which should mark our own personality forever. These include the ability to go to the essence of things, and not allow the self to be affected by appearances or what is secondary; it means to be other-oriented, to remove excessive attention to self. We will be distinguished by some typical attitudes: tenacity and courage in pursuing undertakings without distraction; absolute fidelity to what is started, seen in the desire to constantly start again in spite of and through disappointments and difficulties; dedication to and consideration for the other, whether one or many, which becomes evident in an ever greater sensitivity to personal and community situations of difficulty or emergency. Finally, we will be distinguished by a constructive and preferential relationship with the people we live with, one that generates hope, rehabilitation, consideration, joy, physical and psychological well being. As a result, the human maturity of the witness demands the ability to seize the time with its rhythms, cadences, successes and difficulties as s/he proceeds very slowly and by tiny steps. Such slow and persistent action goes hand in hand with a careful study of the history of the person and with definite actions. In her/his concerned and generous love, however, a great plan is revealed which has the unmistakable mark of the divine.

24. Comboni puts three attributes on the same level in the description of the missionary from a merely human point of view. They are: the superficial (concerned with appearance); egoism (concerned with self); and neglect of the spiritual good of others (having no concern for the well being and conversion of souls) (cf. W 6655). It is like saying that being closed in on oneself is the same as being closed to God and to others. Therefore, for the missionary, human maturity means “welcoming everything and everyone”.

25. Nowadays we are continually being told that the Holy Spirit is the principal agent of mission; and that is right. Without him, any beginning, continuity and effectiveness of the mission is un-thinkable. In other words, mission cannot be accomplished without a starting point which is able to constantly revitalise the activity. Now, in combonian language, we have to say that there is no mis-sion unless there is a vision that points to the reality on which everything is founded and moved from the inner core. Therefore, we members of the Comboni Family should be constantly asking ourselves about the vision that motivates us and the mystical experience that animates our activity. It is not enough to affirm, as Karl Rahner said, that the Christian of tomorrow will be a mystic or he will be nothing, but we need to be conscious of the kind of God we have discovered and which we then proclaim to others. And so we see in Comboni something different and original which affected his activity and affects ours.

26. In his contemplative gaze, Comboni focuses on the love of the Father which flows from the Heart of the Son and reaches out in the abundance of the Spirit to those who are marginalised. God and his people in trouble, the open Heart of the Saviour and people who are oppressed and abandoned, the Crucified Good Shepherd with a pierced heart and the Africa or “Africas” of those who are ignored, enslaved, hungry and cut adrift are now inseparable. It is impossible to think of one without the other; it is impossible to believe in the love of God and forget the brother or sister in trouble. The Plan for the Regeneration of Africa, the Magna Carta, affirms it categorically. Comboni wrote, “… the catholic”, did not allow himself to be influenced through “the miserable lens of human interest”, but by “the pure light of faith” in which he sees “an infinite multitude of brothers and sisters who belong to the same family as himself with one Father in heaven.” Then he felt him-self “carried away under the impetus of that love set alight by the divine flame on Calvary hill when it came forth from the side of the crucified one… and drive him towards those unknown lands. There he would enclose in his arms in an embrace of peace and love those unfortunate brothers of his” (W 2742). We must always proclaim the Divine love, in which we profess to believe, by the liberating service we freely give to our most abandoned brothers and sisters.

27. At the heart of mission is the loving and wounded Heart of the Triune God which turns to look at the missionary and at Africa. Our response is a “nuptial gaze” on the God whose heart is moved by the sufferings of the peoples. The way we look towards God has a bearing on our attitude towards others. In the Rules of 1871, Comboni wrote of the importance of … “ a heart that burns with the pure love of God and to keep one’s eyes fixed on Jesus Christ, loving him tenderly and seeking to understand the meaning of a God who died on a cross for the salvation of souls” (W 2705, 2721). The holiness of the missionary lies in allowing oneself to be enlightened by the complete openness of God towards those no one cares about, in order to allow oneself to be carried for-ward by the movement of this same love.

28. Comboni was not concerned with teaching ascetic statements, neutral definitions or general concepts about God’s love. The God in whom he believed and whom he followed is the same God who loves Africa and who also died for the Africans. This God has a merciful face which is made up of a great number of human faces with all their joys, sufferings and expectations. Important con-sequences for Comboni arose from this Heart of God which beats in unison with the joys, sufferings and expectations of every human heart, and from this Cross on which God died for the most forgotten in body and spirit.

29. The first consequence is to remain faithful to the real dimension of the love of God. And so he was always expanding his attention and concerns. The love of God, which is at the origin of mission, is never exclusive but rather inclusive. In fact it is dynamic and so tends to include, to bring to mind and to embrace even that which we may seek to wipe out from our memories because it is dis-tant, different or alien. In a sense, Comboni expands on what Paul says in Galatians: “He loved me and gave himself for me” (Gal. 2: 20), which becomes: “He loved me and gave himself for us, for Africa.” In 1880 he wrote to Giulianelli, “Pray and ask others to pray for me… so that we all become holy in saving Nigrizia” (W 5976).

30. The second important consequence is the turning upside-down of the main quality we attribute to the Heart of Christ – not to be consoled but to console, to suffer with. Comboni perceives the mystery of the open Heart of the Crucified, which for him is the source of mission, not as the con-soling of God but rather as God who consoles, bears the wounds and heals the scars through the scars of his Son. In the words of Comboni, “The thrust of the lance reached even the heart of Af-rica” (W 1733). At the beginning of the mission is a holiness of God which is described in terms of empathy rather than in terms of separation and distance. It is not the separation of “be holy as I am holy” (cf. Lev.11: 44-45; 19: 2; 20: 7), but rather the closeness of the God of Hosea who exclaims, “Ephraim, how could I part with you? Israel, how could I give you up? …My heart within me is overwhelmed, my whole being trembles at the thought… for I am God, not man; I am the Holy One in your midst and have no wish to destroy” (Hos. 11: 8-9).

31. And so, we not only have a God who is close to humanity, but one who cannot do without hu-manity and its history. In fact, according to the prophet Hosea, the worst threat God could make was, “I shall love them no longer” (Hos. 9: 15). It would be impossible! There would be complete vacuum. It would mean not only the abandonment of the people by God and therefore the destruction of the people, but it would result in the negation of God himself: the refusal of God to be God. Holiness, therefore, on which mission rests, means first and foremost God’s closeness to us. The experience of the love of the Triune God through the Heart of Christ, is the experience of a God who takes on himself the evil of the world. He is a Father God who, moved by His Spirit of love, takes upon himself all wrongs and pays the price for his children through his own Son. God has borne the burden of his sons and daughters.

32. This insight suggests extraordinary consequences for us. It would mean not to shake off the responsibility for others, but to take on their wrongs; not to label and judge the faults of others but to carry them together; not to expose their wounds, but to heal them together; not to close oneself in an independent spiritual solitude, but to pray together. Our society and sometimes even our Church and our communities follow other trends: you have done wrong, now you will pay; today you are efficient, I applaud you; tomorrow you are no longer efficient, I cast you aside; today you are in a weak position, an illegal, a refugee, desperate, so I reject you; either you accept these conditions or, rather, subconditions of work, or you go… The aim of mission is to carry the compassionate love of Christ to others. To live by this love is, according to Comboni, the first and absolute condition for evangelisation.

33. Comboni’s deep love of God was noted by many. Sr. Matilde Corsi, a Comboni Missionary Sister who first knew Comboni in 1877, at the process in Khartoum said, “His love for God had no limits” (P. II, p.1265). Sr. Chincarini noted, “The Lord was his only life. He sought to instruct everyone, and especially the Sisters, in the spirit of prayer and limitless trust in the Lord. In the face of difficulties he would say, ‘Let us trust in God and rely on him always’” (P. II, p.1255). Said Mohammed Taha, a Muslim and a slave merchant, in his statement never tired of saying that, “Comboni loved God very much. He knew that everything came from God and he hoped in him. We recognised his great faith from the way he spoke” (P. II, p. 1270).

34. All the witnesses were impressed by his constant prayer. It often took place at the most inconceivable and difficult times and most of all at night. Sr. Chincarini reported that, “Because of his many concerns, the Servant of God did not sleep much and from his brief rest he stole some time to be with God especially for the recitation of some of the prayers he had not been able to say during the day. He was often seen late at night walking in the courtyard with his rosary in his hand” (P. II, p.1255). Rafail Rigsalla Habasci, president of the Coptic-Orthodox community in Khartoum, in his statement said, “The face of the saint was cheerful” (P. II, p. 1269), on his face he reflected the light of Christ.

Comboni’s legacy to us in his own words:

“…To inflame them with a charity which has its

source in God and in the love of Christ…” (W 6656)

35. To inflame them with charity… means to return constantly to the heart of mission which is the immeasurable love of the Father who comes to us through the pierced Heart of his Son and sends us in the Spirit. It is from here that, as individuals and as communities, we take shape and receive our missionary identity. The conviction that we have a unique personal call is established here: “My God, I delight in your law in the depth of my heart” (Ps. 40: 8). At this source we drink in the knowledge that we have been signed for ever with the seal of the paschal mystery of death and res-urrection, so that even in our own bodies we have the expression of generous divine love: “…you have prepared a body for me…And so I said, Here I am, O Lord, I come to do your will” (cf. Ps. 40: 7-8). At this source we know that we are sent in the totality and uniqueness of our self: “Consecrate them in the truth… As you have sent me into the world, I have sent them into the world, and for their sake I consecrate myself so that they too may be consecrated in truth” (Jn. 17: 17-19).

36. To inflame the mission with the love of God means therefore to place consecration at the centre of it: the infinite love of the Father for each one of us before our good will; the compassionate love of Christ before our solidarity; the person of our brothers and sisters before ourselves; the total gift of ourselves before anything we might possess, gain, or give, and so on. It means being able to say in all truth, following the example of Comboni, “…wholly consecrated to the glory of God and to die for Christ” (W 6796), the only true passion of my whole life…is that Africa be converted.” (W 6987)

37. To inflame them with charity… means to recognise anew the centrality of consecration in missionary life. The Apostolic exhortation, Vita Consecrata, states, “…The sense of mission is at the very heart of every form of consecrated life”(VC25). This is not just a generous and efficient human commitment but apostolic life, that is, true consecration, a response to a divine grace received, a conscious binding of self to the divine love which calls uniquely and sends uniquely; it is a constant seeking for the Christ of a thousand faces. Therefore it involves, not just a part of the affections, of the gifts, of the plans or of the goods qualities of a person, but of the whole person without reserve. ”With all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength” (Deut. 6: 5), because it is precisely in this total Trinitarian love that, by grace, we have been chosen.

38. For us, the vows become the only possible response to so much love. They are a personal, unique and total response to a unique and total call and therefore less concerned with juridical ties, laws and moral codes, and more with the joyous awareness of having been accepted by the grace of God to be a part of the dynamic love of the Heart of God for the world. The idea that religious consecration is a diminishment, that it creates conflict or is simply an efficient tool added to mission needs to be dismissed. Consecration is at the heart of mission because it is in their consecration that missionaries, through grace, become the personal expression of gift. This gift is the most freely given, the most unselfish and the most steadfast in the measure in which it takes the form and the being of the heart of Christ and of the Cross. The gift that saves, springs from a person’s deepest motivations and, therefore, it is in the three vows that everything leads back to the uniqueness of the person.

39. A continuous vigilance on the quality of our consecrated life will ensure the authenticity of our evangelising mission. It helps us to discover whether we are carrying Christ or ourselves, whether we serve people or use them, whether we help them to be rooted in Christ or we tie them to ourselves, to our plans and to our ideas. A life of consecration lived as total offering of ourselves to Christ will tell us if we are really dedicated to others and able to grow together with them in a deep and transforming spiritual experience.

40. To inflame them with charity… becomes concrete in a constant return to the wellspring and therefore in looking closely at the kind of personal and community prayer life we have. Comboni used to urge to pray with the fire of charity and not to be satisfied with routine and formulas, but to make of prayer a time of personal and community encounter and confrontation with whatever in us, in our community life and in our situations is in need of God, his light and his strength. We are urged, therefore, to rediscover prayer as an integral part of mission, in which we turn to God through specific fixed times and progressively become free from individualism, from overactivity and from the anxious seeking after efficiency and results; all these things mask an excessive concern with self.

41. To inflame them with charity… means to experience that the true meaning of consecration and of mission is the person of Christ who must be proclaimed. If the nature of consecration is the grace of being called to follow Christ, the heart of consecration is to proclaim Christ. This too is peculiar to Comboni. It is amazing how often he speaks of an urge to proclaim that makes him an announcer of salvation, because of the bond with the person of Jesus Christ. “We work only for Christ and for the glory of his name and to win the souls of Africans” (W 6660). Here Comboni is repeating, with the same emphasis as St. Paul, his condition as a prisoner for the love of Christ. It does not matter that he may be scorned, criticised or challenged, Christ must be proclaimed. “…The sufferings, condemnation and death for you, must be lived out in us. We must suffer, be despised, slandered, (you, no; me, yes), perhaps condemned to die, …but all for our beloved Jesus! I do not care for the world or the opinion of the world. But for Jesus Christ’s sake even sacrifice and martyrdom is very little” (W 6664).

42. We are not called to be silent then, but to offer the word of life, the direct, explicit proclamation given in humility and conviction and without arrogance. The proclamation is not the result of an external command, but of a state of identification. Therefore the proclamation continues to be the fundamental essential before which nothing must be given preference. The words of St. Paul ‘…he died and was crucified for you’, flow from the lips and pen of Comboni and link the grace and the responsibility to proclaim Christ with the unique, total and nuptial personal relationship with him: “We suffer for Christ and that is all” (W 6689). “I am totally consecrated to the glory of God and to die for Christ” (W 6796).

43. To inflame them with charity… means to resolutely take the road of gospel radicalism, that is, of prophecy. It means to leave everything so that the following of Christ, which we have vowed to undertake, may become mission. It means to place the Kingdom of God above everything else (Mt. 6: 33). If we risk everything, if we seek the Lord and his plan and allow ourselves to be led by the Spirit, then prophecy-mission, the fruit of consecration, will be born.

44. Anyone who clings to the love of God and sees that as the driving force behind the dynamism of mission, as it was for Comboni, cannot but be a community person. In the Rules of 1871 he wrote that one must be “an inconspicuous individual in a group of workers” (W 2700). It is the anonymity of the person who does not work for self, in an undertaking that is, however, not anonymous.

45. To speak of Comboni as a witness of the evangelising community could seem a contradiction or at least rather forced. He did not seem to be so much a community man as a giant whose distinct individualism and abundant protagonism led him to extreme activity. His same undeniable love of the Church seemed to be a love for a rigidly structured and rather conservative community. Rather than to a community, understood as a communion of persons, he seems to have referred more to the strength of its structure and organisation.

46. A more objective and profound observation, nevertheless, will reveal instead that Comboni’s love of the Church, his “doing nothing without the Church” (S959. 971. 4088), was the distinguish-ing mark of a man profoundly convinced that the mission was opening new ways, developing and finding its truth precisely in community. Daniel Comboni showed himself to be a community man in practice long before he was so in thought. He was continually seeking out people and companions even before he looked for help and funds. Mission arises from a “trinitarian koinonia” and those who carry it out cannot but work together as collaborators in this ongoing task of bringing together the scattered children of God. Speaking of Comboni, Sr. Matilde Corsi emphasises not only his evident spiritual qualities, but also the care he had for his missionaries. She stated, “I knew the Servant of God from when he was made Bishop in 1877 until he left for Africa for the last time in 1880. The impression I had was of a holy person who thought only of God, his people and his missions.” (P. II, p.1264). The fullness of the love for God is in proportion to the awareness of the responsibility towards one’s brothers and sisters.

47. In 1868 Comboni began to carry out his Plan together with a group of three Camillian Priests, three Sisters of St Joseph of the Apparition, sixteen African teachers and a few lay Brothers. The fact that he immediately showed his full and complete trust in the Africans was of immense value. So too was his recognition of the primary importance of women in evangelisation. He was the first to bring Sisters to Central Africa. On the 5th of May 1878 he wrote to the Superior General of the Sisters of St. Joseph of the Apparition, “Five Sisters from my Institute in Verona are now in Berber. They will be going to a new mission that I will be setting up soon. My secret, based on my long ex-perience of 21 years, is this: in a mission station in which there are six or seven Sisters I only need to put two missionary priests. Two priests and six Sisters in a Mission in Central Africa will do more good than a Mission with twelve priests and no Sisters. This is a fact” (W 5117). “The Sister of Charity in Central Africa is as useful as a missionary priest; the priest would achieve little without the Sister” (W 5442). Besides this, the commitment with which he founded his two Institutes, of men (1867) and of women (1872) is beyond dispute.

48. Comboni was a man who made contacts, a communicative man who liked to join forces with others, who engaged in dialogue, who asked for others’ opinions. It was seen in his search for help from the most varied sources, Camillians, Benedictines, Salesians, Divine Word Missionaries, Trinitarians and the Sisters of St. Joseph of the Apparition. Even his proposed Central Committee, the Central Directive Committee of the Plan, which involved lay people and institutions, showed his communitarian-ecclesial-catholic mentality. He sought to organise and protect the alliance made up of the diversity of charisma and the unity of intent formed for the overall good of the work.

49. The concept of evangelisation in community can be worked out alongside those actions of his that reveal a sense of community. This is seen in the conviction that took shape in the drawing up of the Regulation of 1869 and of the Rule of 1871. The Institute was conceived of as a “cenacle of apostles” (W 2648), a unifying centre from which the energy for mission springs and the life of which is described as a “living together like brothers and sisters” (cf. W 1859, 2495, 2497). Evan-gelisation, according to him, must recoil from isolated individuals. No one must be left alone in a mission, or the quality of witness will suffer, devotion will wane and the moral integrity of the mis-sionary will be in danger. (W 1317, 4241, 3189)

50. This spirit of evangelising community-communion that gives stability and authority to the work is confirmed in Comboni’s final meaningful gesture before he died. At that time there were in Khar-toum very young Sisters, none over the age of 23. Among them were Sr. Francesca Dalmasso and Sr. Elisa Suppi. Five days before he died he went to encourage them and to receive their promise of fidelity to the mission. Fr. Giovanni Dichtl, one of the five missionaries who were in Khartoum wrote, “On the afternoon of the 8th he wanted me to promise once more to be faithful to the mission. I did. I swore that I wanted to die in the Vicariate. Comboni said to me, ‘Africa or Death’…” In these final promises, requested and given freely by even the youngest, and in the words spoken before he died, “Do not fear, I am dying but my work will not die, there will be a great deal to suffer but you yourselves will see the success of our mission” (P. II, p. 1255), there is authentic traditio, a real awareness of continuity expressed in words and gestures, completed and given meaning by the young people around him.

51. To root the future of the mission in the community is not just a formal handing over, but the most convincing expression that the mission finds its real accomplishment in community and its confirmation. This is an aspect of holiness because it indicates a movement from individualism to community. In order to revitalise the mission and ensure its continuity it is imperative for us to revive the meaning and practice of fraternal communion and consider it an essential element of authentic evangelisation even today. Every specific missionary activity must spring from the roots of fraternal love in community, “The whole group of believers was united, heart and soul” (Acts 4: 32). That is, every apostolic action must spring from that goodness of brothers and sisters who live together (Ps. 33), and which makes them recognisable as “those who have been with Him” (Acts 1: 21).

Comboni’s legacy to us in his own words:

“...to become a little Cenacle of Apostles…. Rays

which give both light and warmth..” (W 2648)

52. Two complementary elements are necessary to live in community with renewed joy: to continually revive the meaning and the practice of a fraternal community as an essential element of re-ligious life and consider it as essential for authentic evangelisation. The fecundity of religious-missionary life depends on the quality of fraternal life lived in common. Even more, the present renewal of mission goes through a search for communion and community.

53. Communion is lived out as life in common. It becomes a life of missionary radiance insofar as it is chaste, poor and obedient. All our relationships with the members of the Comboni Family and with others are sustained by the unique love of Christ. If these relationships are true then they should be expressions of fraternity. The more we grow in love, the more the heart expands and becomes able to include more people. All our goods, whether they be spiritual or material, must al-ways be at the disposal of the community. And so each one will weigh personal needs against those of the brothers and sisters and not demand the right to have, but rather the right of the brother and sister to receive support. Obedience will be the expression of submission to God, to authority, to the brothers and sisters in order to become ever more “one heart and one soul”, so that the individual and the community can submit to “what the Spirit is saying to the Churches” (Rev. 2: 7).

54. John Paul II warned the participants of the Congregation for the Institutes of Consecrated Life and the Societies of Apostolic Life about the activism which sacrificed the quality of community relationships. “If the public witness of religious life in community is placed after apostolic action and personal fulfilment, then the religious communities will lose their evangelising power. They will no longer be what St. Bernard defined so well as ‘scholae Amoris’, that is, places in which we learn to love the Lord and day after day to become children of God and therefore brothers and sisters.”

55. To become a cenacle… means to concentrate first of all on the positive aspects which can build a climate of acceptance and collaboration with our brothers and sisters. At the heart of a true community lies the realisation that our life together is the greatest gift that God has given us, and in this life his grace and love become visible and effective. We are urged, therefore to revive the true aim of the evangelising community: put together by God’s grace to live and proclaim the gospel. This aim of the love of God experienced together and shared with others both within and outside the community, will help us to become more balanced and to sustain personal growth because the aims of the community are reached through healthy and profound relationships between its members. The required duties will not then be mere bureaucratic functions but part of a shared commitment in which each one is interested and involved in the measure in which each one is able and available.

56. To become a cenacle… means to become more patient, understanding and non-judgemental and to forgive generously. It means to believe in the efficacy of everyday gestures, “the hidden virtues” which change us, the people we live with and the quality of community life. Above all it places the attitudes of reconciliation and forgiveness at the heart of community living. Only reconciliation and forgiveness can restore the ability to recognise the face of a brother or a sister in those who are close to us and can give us the joy of living together and the hope of proclaiming the Gospel as a freedom we already experience.

57. To become a cenacle… means to be aware that the community is also an imperfect and ambivalent reality. We all experience the differences, the misunderstandings, the blocks, the incompatibility and the lack of communication. What is important is not to give in to what can undermine community life such as defensiveness, silence and resistance, the excessive search for interests and support outside the community, isolation and individual management of one’s time and talents, to live and let live because we have been hurt or we feel unable to live together and so on. To get used to these attitudes increases the sense of frustration and delusion.

58. As there is a real danger that our love will grow cold (cf. Mt. 24: 12), we need to stir up the fire so that the community does not become a mere living side by side, nor a team of religious workers nor a hostel. If this happens, then we will need to restore excellence to our community by planning and rediscovering spiritual discernment in view of making evangelical choices. Technical research, although necessary, is not enough to discover the will of God for the members and the programmes of the community as an evangelising fraternity. Through community spiritual discernment the community becomes a family in which the different cultures are accepted and welcomed and in which each one is committed to carry out the will of God that has been discovered together.

59. To become a cenacle… means to recover the historical memory of the Institute and of those people who have lived out the charism in the best way. If we can grasp their spirit and their most significant achievements then even today we can guarantee continuity and stable tradition and at the same time we are given an incentive to move towards new ways of community living and new experiences of communion for mission. When we maintain a healthy and creative link with the tradi-tion of the Institute our joy and confidence increase and together we seek ways that are not yet clear, ready to suffer together for lack of success or persecutions. Sufferings are a sign of a community sustained by the Spirit and therefore able to evangelise.

60. Another aspect of the holiness of Comboni, which still speaks today, is a reminder of a discipline of the mind and of action resulting in options and in practical appropriate choices. Comboni did not stop at stating principles nor did he act just anyhow, but he had his own method as outlined in the Plan. It is common knowledge that this is the Magna Carta of his mission strategy, which is based on two fundamental statements. One is the aim, “To save Africa with Africa”, and the other concerns the basic option and the dynamism inherent in such an option, “The poor as protagonist of their own ransom.” One underlines the possibility of the Africans to become alive and active for themselves in Church and society. As Comboni wrote, “Couldn’t Africa be used to convert Africa? Our thoughts became fixed on this great idea; to regenerate Africa with Africa seems to be the only plan to follow in order to achieve such a glorious conquest” (W 2753). The other statement says that, in this process of integral salvation (conversion and liberation, personal and structural autonomy) the starting point are the poor, the least regarded. At the end of his Plan he writes, “… so that the conquered, not won over by force, but conquerors of themselves and their nature, will achieve true religion through Baptism as well as the great benefits of civilised life” (W 2791).

61. This was the action of a saint because at the root of it all is a positive theological vision, the possibility of redemption for the African. The erroneous impediment based on the “ancient curse” of Canaan (Gen. 9: 25-27) would not stop Comboni, but further stimulate him to dedicate himself with urgency and greater wisdom to his African brothers and sisters. Comboni’s view of Africa and the Africans was positive. He saw that God’s whole plan of salvation was for them too and so it was unthinkable that there should be only emptiness, deficiency and backwardness in them which would justify their being left aside and despised. He saw that there must be potentiality and latent energy put there so that they could redeem themselves.

62. In evaluating the instinctive love of Comboni towards the Africans we learn that the witnesses used only one word to help us understand what kind of love it was. Comboni was called the “Father of the Africans.” Erminia Mersilla was a former slave who had been picked up and ransomed by him after she had been beaten and thrown into the garden of the mission in El Obeid. In her evidence she said, “The Servant of God seemed to me to be a father. He was the father of the poor and that was what they called him in his time. He helped everyone and because of this everyone loved him. He protected the poor slaves and defended them even before the civil authorities; for this reason the slave traders feared him greatly” (P. II, p. 1259).

63. People were astonished by his extraordinary closeness to the Africans. We are all called to go beyond that astonishment which is normally founded on a partial understanding, because it is identi-fied almost exclusively with a condescending attitude of the eternal benefactor. Comboni goes beyond that. He perceives the energy necessary for self-recovery because, besides being able to grasp the innate qualities of a person and distinguish them from negative behaviours induced by an unfavourable history, he starts with the objective value of every person in the light of redemption, that is from the Crucified Christ. The crucified ones of history have a substantial character because they are identified with the Crucified One.

64. Comboni has an ecclesial vision of faith and so he makes an option for the poor as a transforming power and proof of the truth of the Church and of a just society. In other words he believes in the transforming power of the poor. His unique love for the poorest of his time is not exclusion of anyone, but an option. His incessant travels, the journey with “his Africans”, the drawing up of a demanding Plan of selfrecovery were, in effect, an option. Behind his project of a selfsufficient Nigrizia, there is an option and not just a generous action. His contemporaries were aware of this.

65. Somit Habib, a Muslim who gave evidence at the process in Khartoum, helps us to detect the range of Comboni’s charity and how far he was prepared to go towards helping. “Bishop Comboni was the father of the poor, he helped everyone, even the whites…. He took the slaves who had escaped from their masters into the mission and defended them even in front of the government” (P. II, p. 1260). Sr. Elisabetta Venturini was a Comboni Sister who accompanied Comboni on his last journey to Africa in 1880. She noted, “The Servant of God would help in any kind of suffering, but he preferred to help children, women, the sick and the elderly poor. To them he gave all he could” (P. II, p.1258). Khatib, a carpenter and domestic worker from Khartoum added, “He was always smiling when he was with the people but he was tough with the slave traders in order to defend the poor, ill-treated Africans.” (P. II, p.1257).

66. This resolute option for the “poor and impoverished” is a particular legacy of the holiness of Comboni and of his way of proclaiming the Gospel. It is a truly holy option because it means choosing the Cross of Christ as a guide to one’s life and plans. In practice it means choosing the way of littleness, as a reminder of the acts of injustice which are continually being committed against those who are weakest. It is also a prophetic indication of a different way of life, in which simplicity and solidarity are the foundation of a just society in which there is room for everyone.

67. An option of holiness such as that of Comboni is ever more necessary in the face of the challenges arising from three phenomena which shake the foundations of civil and religious society today. These are multiculturalism, secularisation and globalisation. In a multicultural society, towards which we are rapidly moving, the prospects are either dialogue, mutual understanding and therefore an intercultural society or else cultural and religious clashes. In a society, which is becoming ever more secularised, there is a new dilemma: to regulate everything in the cold light of reason, go with the demands of finance, profit and technological development or to reintroduce the values of transcendence, solidarity, faith, justice and equality.

68. In a world, which has become globalised from the point of view of economy, politics and information we find ourselves facing a point of no return. Either globalisation is truly inclusive and for everybody or else it is exclusive and the tool of the powerful and fortunate few who seem to want to decide the fate of humanity. We see before us a cruel gulf dividing the nations. Just think of the two billion people who live on less than two dollars a day. The divide between the rich and the poor is continuing to widen. According to the United Nations’ Report on Development, the ratio was 1 to 30 in 1960, 1 to 60 in 1990 and 1 to 74 in 1997.

69. In his option for the poor, Comboni showed us a way. It is not about formulas, slogans or a temporary feeling, but a permanent choice. To be on the side of the poor from Comboni’s viewpoint means to be linked with them “nuptially”, indissolubly. In fact, Comboni calls Africa “my beloved” (W 6752) and says, “Africa and the Africans have conquered my heart” (W 941); “… I have lived only for Africa and I will die for Africa” (W 1438), and “I will die with Africa on my lips” (W 1441). To opt for the poor means to believe that “the poor”, the “crucified peoples” and “the little ones” are the victims. Today they are what Bishop Oscar Romero called “the violated divinity” and so they are also instruments of salvation for everyone. They call us to truth, insofar as they make us see what we do not want to see or we seek to hide. They call us to solidarity insofar as they make us understand that material things are not enough to heal injustice, but solidarity based on selfgiving is what is needed. And finally they call us to a new civilisation based on a culture of simplicity which does not mean universal impoverishment, but a new ideal of life, a true humanisation of relationships between people and nations.

Comboni’s legacy to us in his own words:

“…I will die with Africa on my lips…” (W 1441)

70. To die with Africa on the lips… means to ask ourselves if our “option for the poor” is to be “doing for the poor” or is a creative “living with the poor”. “To die with Africa on the lips…” means to live the choice we have made as a “nuptial” tie with people and situations. As Comboni said, “I am returning to you and will never cease to be yours and everything is consecrated for ever to your greater good” (W 3158). It also means, therefore, to look at the quality, the depth and the sincerity with which we say we believe in the others. This is necessary in order to give a credible form to the words “To save Africa with Africa”. If we have a respectful care for the needs of people and therefore our journey with them is authentic, then they will be able to release all their potential and find new ways of being. We will not be able to respond to the real expectations of the peoples, of society and of the local Churches if what they see in our eyes is distrust.

71. Comboni’s fidelity underlines for us more than ever the truth that “to make common cause” needs to become ever more concrete. This can happen in the way we show we are near to people and by an attitude of humility, of friendship, of trust, of sharing, careful that our presence is an incentive and a true common participation in the carrying out of pastoral and social programmes. At the same time we must distance ourselves from the ambiguous attitudes of those who either take the place of the weakest by doing, deciding, carrying out everything or those who become passive and distant spectators with the excuse that “their” time has come now.

72. To die with Africa on the lips… means to consider the work of evangelisation as a whole in which the local Church and lay ministers have to play a particular role. In the journey towards the autonomy of the local Church and the substantial and creative expression of cultural differences, we have the responsibility of becoming ever more competent in training leaders both in the religious field, (seminaries, catechetical centres, universities etc.) and in the sociopolitical field. This also requires a much greater appreciation of the value of the woman. These demands of formation and training dictated by the mission require courageous and long-term planning alongside the various organisations of the Church and society. The option for the poor also demands a more specific formation of missionary personnel to be carried out in a more effective programme. Mgr. Gabriel Zubeir Wako, the Archbishop of Khartoum, noted that “Evangelisation cannot be improvised. Comboni spent a great deal of time and energy to ensure a profound human, intellectual and spiritual preparation for his collaborators. He knew this would be necessary in order to enable them to dedicate themselves to such a demanding task.”

73. To die with Africa on the lips… in the present sociopolitical climate means to commit oneself to the cause of justice. The unifying vision of the Plan between proclamation and giving the poor a voice, so that they are able to regenerate and transform their own situation, needs to be kept in mind. If this unity of vision and its practice as proposed by Comboni are not respected and if we emphasise the spiritual aspect to the detriment of the social and vice versa, evangelisation will be gravely flawed. Evangelisation deprived of its spiritual aspect will not have real power to transform (it will just generate new masters) or else, if it is confined to Church environs and a disembodied spirituality it will become meaningless and inadequate. History will continue to produce victims of injustice.

74. In this area of justice, peace and integrity of creation, we are called to build bridges of commu-nication in order to be in touch with the issues and the achievements of the Churches and the forgot-ten peoples. In a world that prefers to ignore, isolate or undervalue the weak, we need to help it to understand their cultural and social values so that their precious contribution to the birth and to the security of the heritage of the whole of humanity may be recognised. In a world which faces the challenge of intercultural and interreligious life together, we are called to open up channels of communication in order to help mutual understanding and mutual appreciation.

75. To die with Africa on the lips… compels us as members of the Comboni Family to question ourselves about what we still need to do in order that the motto of Comboni, “To save Africa with Africa”, may reach its fulfilment.

76. After Daniel Comboni’s death, according to the testimony of his second cousin Eugenio, “A missionary came from Africa to comfort Monsignor’s father and gave him a pectoral cross made of brass. It was Monsignor’s battle cross, as he called it. The cross he normally wore, as he kept the valuable one given to him by Pius IX out-of-the-way, in the event – he used to say – St. Joseph got a cold, in which case he would have sold it. I personally heard don Daniele say this. After the death of Signor Luigi that brass cross came into my hands. I keep it as a precious memento and I would not like to depart of it” (P. II, p. 1235).

77. With the brass cross constantly hanging from his breast, Comboni, without having to use words, makes us understand the essential element of his missionary holiness: his authentic approach and the radical evangelical direction of his life that kept him moving on in his ideal. It seems that Comboni never had to sell his valuable cross, because the brass cross did well enough