Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

This Sunday’s Gospel continues the Beatitudes from the “Sermon on the Plain” in St Luke’s Gospel (Lk 6:17-49). Jesus sets out how his disciples should conduct themselves. The essence of his message is: “Love your enemies.” This is one of the most radical passages in the Gospel, requiring a profound upheaval of our instinctive reactions and social behaviours. [...]

Opening the Doors of the Heart

“But I say to you who hear: love your enemies.”

Luke 6:27-38

This Sunday’s Gospel continues the Beatitudes from the “Sermon on the Plain” in St Luke’s Gospel (Lk 6:17-49). Jesus sets out how his disciples should conduct themselves. The essence of his message is: “Love your enemies.” This is one of the most radical passages in the Gospel, requiring a profound upheaval of our instinctive reactions and social behaviours.

In this passage, Jesus uses no fewer than sixteen imperatives. However, his words do not constitute a new legal code but should be understood in light of the Beatitudes. These are words of divine wisdom that lead us to the very heart of God. Paradoxical as it may seem, Jesus is giving us the key to access the Beatitudes.

The history of salvation and the Christian life is a journey, a transition from the order of justice (“an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, a hand for a hand, a foot for a foot”: Exodus 21:24) to the order of grace (“Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful”: Lk 6:36). It is a shift from the logic of retribution to the logic of gratuitousness, a radical change that Jesus proposes to his disciples. In the second reading (1 Corinthians 15:45-49), St Paul presents this process as the transition from the “first Adam” to the “last Adam,” from the earthly man to the heavenly man.

The Waves of Divine Love

Jesus’ discourse unfolds in four successive waves, each marked by four imperatives. This is God’s Love seeking to cover the whole earth—like a divine tsunami—drawing us into this adventure.

1. The first wave consists of four imperatives directed at the disciples:

“To you who hear, I say: love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you.”

The Greek verb used here for “love” is not philein (to befriend, a love based on reciprocity) but agapan (to love with a completely gratuitous love). This love is expressed in doing good, blessing, and praying for those who are against us.

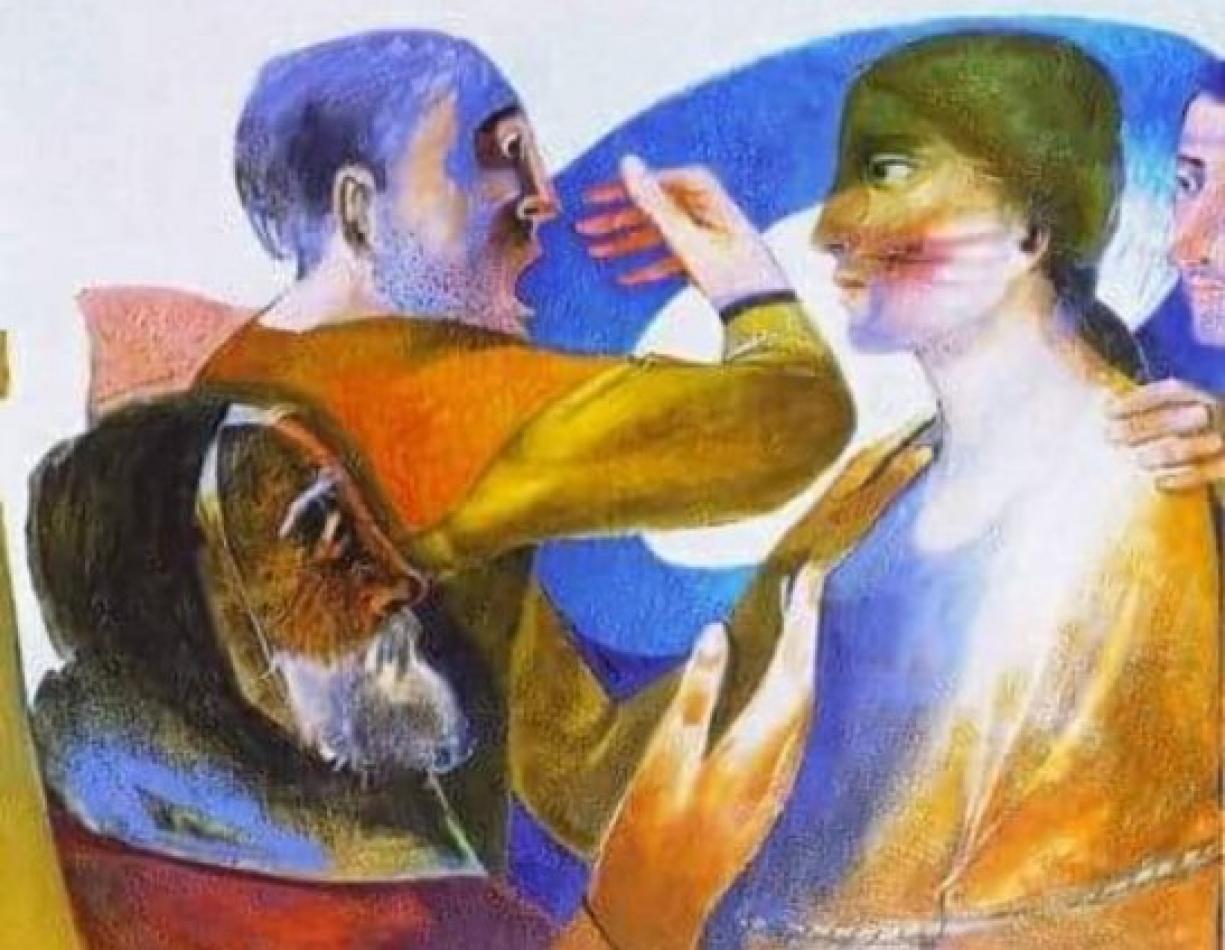

2. The second wave presents four concrete examples, expressed in the second-person singular to make the discourse more direct and personal:

Offering the other cheek to the aggressor, not withholding one’s tunic from the thief, giving to anyone who asks, and not demanding back what has been taken.

These are not rules to be followed mechanically, nor do they imply renouncing one’s rights, but rather, they call for a response that does not mirror evil with evil and renounces violence. This requires discernment in each situation of injustice. The aim is to overcome evil with good: “Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good” (Romans 12:14-21).

3. At the heart of Jesus’ discourse is the so-called ‘Golden Rule’:

“As you would have others do to you, do likewise to them.”

Jesus gives four reasons for this: three negative and one positive.

Three negative: What merit, what beauty, what goodness, what generosity is there… if you love those who love you? If you do good to those who do good to you? If you lend expecting to receive in return? Anyone can do that! Then he adds a positive motivation: “Rather, love your enemies, do good, and lend without expecting anything in return, and your reward will be great; you will be children of the MostHigh.”

4. The passage concludes with an invitation to ‘be merciful, as the Father is merciful’, along with four further recommendations to make us more like God—two negative and two positive: Do not judge and do not condemn! Forgive and give!

What Law Governs Our Lives?

“An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” This principle seems barbaric and cruel to us today, something no one would dream of applying—at least, that’s what we tell ourselves. But is that really the case?

We may not physically harm others, but we can certainly destroy them with words—dragging their reputation through the mud! Or, in our thoughts, we may nurture the desire for revenge. We can render them worthless through indifference. Or even, in our hearts, harbour hatred and erase them from our lives altogether!

The truth is, the human heart has not changed; it has simply become more subtle and refined! The law of retaliation still often governs our relationships, sometimes even leading us to the temptation of manipulating God to justify our violence. A striking example of this is the war between Russia and Ukraine unfolding before our eyes. The Jewish philosopher and believer Martin Buber was right when he said: “The name of God is the most bloodstained name on earth!”

Loving the Enemy?

“But I have no enemies!”—how often we hear this said. And yet, we create enemies every day. A real production line. Our ears hear a (negative) piece of news, or our eyes see an (unpleasant) image; our minds process it, our imagination builds on it, our judgment passes sentence, and our hearts react accordingly… We become merciless judges. And how difficult it is to dismantle this mechanism! It requires constant vigilance. St Augustine says: “Anger is a speck, hatred is a beam. But if you feed the speck, it will become a beam!”

Setting the Prisoners Free!

In his mission statement, Jesus declares that he has been sent “to proclaim liberty to the captives, to set the oppressed free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour” (Luke 4:18-19). There are many prisons that keep much of humanity enslaved, but could it be that our own hearts have also become a prison?

Too often, in the darkest recesses of our souls, we have locked away many people, sentencing them according to the law of “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” The Jubilee is a kairos of grace, the opportune moment to fling open the doors of the heart!

Fr. Manuel João Pereira Correia, MCCJ

What do you do for free?

Luke 6:27-38

Introduction

Ernesto says in front of his colleagues at school: “I respect everyone, but if they kidnap my child I certainly will kill the responsible.” Joseph is an employee; one day he comes home upset by anger for the injustice suffered and confides to his wife: “I have to make Luigi pay! When he will need a favor, he will have to ask me on his knees and I will make him wait until when I want.”

The jeweler George was robbed three times by robbers and was also threatened with death; now he keeps a gun at hand to defend himself. Let’s evaluate these three attitudes. We all agree in considering that Ernesto, Joseph, and George are not wicked: They do not attack those who do good, merely they react against those who do evil. Violence, retaliation, revenge have their own logic and can be justified.

Maybe we do not share the way they intend to restore justice, but the goal that the three aim is not evil. They just want to punish and deter those who commit reprehensible actions. We could say that they are just people: They respond good with the good and evil to what is evil. But is it enough to be considered Christians by being just?

Who is inwardly transformed by love and by the Spirit of Christ goes beyond the logic of people and places in the world a new sign: the love towards those who do not deserve it. To internalize the message, we repeat: “Love your enemies, to be sons of your Father who is in heaven.”

Gospel: Luke 6:27-38

After proclaiming the disciples blessed because they are poor, hungry, crying, persecuted, Jesus addresses the crowd who listens to him and enunciates a shocking principle: “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, and pray for those who treat you badly” (vv. 27-28). Four imperatives—love, do good, bless, pray!—that do not leave any doubt about how a Christian should behave in the face of evil. They are the unequivocal evidence that Jesus rejects, in the strongest terms, the use of violence.

Against the guilty, we react instinctively with aggression. We believe that “making him pay,” justice is restored and everyone is given a lesson in life. Jesus does not agree with such hasty solutions. He repudiates the use of violence because this never improves the situation. It complicates it even more and does not help the wicked to become better. It crushes him, triggers the hatred, awakens the desire for revenge and vengeance. Violence may be able to eliminate it, but not to save it. The only attitude that creates the new is love.

There are Christians who recognize, very honestly, that even trying they will not succeed to love those who caused them irreparable damages: those who have slandered them, ruined their career, destroyed the serenity and peace in their family, who—it happens too—killed a family member.

Jesus does not demand that we become friends of those who do us harm. Not even he felt sympathy for Annas and Caiaphas, the Pharisees, for Herod that he dubbed “fox” (Lk 13:32), for Herodias who had the Baptist killed (Mk 6:14-29). Sympathy is beyond our control; it cannot be ordered, it spontaneously arises between people who respect each other, who are attuned each other.

The Master asks to love, that is not to look to one’s own rights, but to the needs of the other.

It is not enough not to respond to evil with evil, with insult to injury. One has to keep oneself on hand to accept others. It is a must to always make the first step to reach out to those who did wrong, to help them get out of their plight.

It is not easy. That is why prayer is recommended. Only prayer puts off aggression, disarms the heart, communicates the feelings of the Father who is in heaven, gives the strength that comes from God’s love. Prayer for the enemy is the high point of love because it presupposes a heart willing to be purified from all forms of hatred. When one puts oneself before God he or she cannot lie. One can only ask him to fill with good those who do evil; and when one manages to pray like this, the heart becomes attuned with the heart of the Father who is in heaven, “who makes his sun rise on both the wicked and the good, and he gives rain to both the just and the unjust” (Mt 5:45).

In the second part of the passage, Jesus explains his request with four concrete examples: “To the one who strikes you on the cheek, turn the other cheek; from the one who takes your coat do not keep back your shirt; give to the one who asks and if anyone has taken something from you do not demand it back” (vv. 29-30). The disciples are not prohibited from demanding justice, from defending their own right, from protecting their properties, honor, and life. They are not cowards who tolerate oppression, abuse of power, harassment towards the weak. Love does not mean to endure in silence, without reacting.

The Christian is very actively committed to putting an end to injustice, bullying, thefts; however, to restore justice, one most reject the methods condemned by the Gospel. A Christian does not resort to arms, violence, falsehood, hatred, revenge. A Christian does not pay evil with evil “… If your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty give him to drink…. Do not let evil defeat you, but conquer evil with goodness” (Rom 12:17-21). When one is unable to restore justice with evangelical means, what remains is for the Christian to have patience. This virtue indicates the ability to withstand, to resist under a heavy weight. When the only way that remains open is to hurt a brother, one who is able to support the weight of injustice shows himself a disciple of Christ.

The passage continues with the so-called golden rule: “Do to others as you would have others do to you” (v. 31). It does not mean that we have to take our selfishness as a measure of good to be done. Jesus just gives a wise counsel on what to do to help those in difficulty. He suggests to ask ourselves this question: if we were in his condition, what would we like others to do for us? How would we like to be helped? Would we be happy if they attack us, humiliate us, would use violence to us? Let us be honest when we demand justice for a wrong suffered. Often we do not seek the good of the other, we think only of taking revenge. We observe for example how, in front of an offender, the behavior of the judge is different from that of a mother. The first renders its judgment on the basis of a code and want to reestablish the rule of law; the second passes over to all the codes, she is guided by her love and think only of recovering the child.

In the following verses (vv. 32-34) Jesus considers three cases of “righteous” people: they love those who love them, do good to those from whom they receive good and make loans and then get the requital. These are people who do good deeds, no doubt, but their behavior can still be dictated by calculation, by looking for an edge.

The expression “what credit is that to you?” It is the parallel text of Matthew that speaks of “merits” (Mt 5:46). Luke chooses instead, and with much finesse, another term; he says: “where is your credit?”, that is, “what do you do for free?” It is the gratuity that characterizes the action of the Christian and that allows us to identify, unequivocally, the children of God. He continues: “Love your enemies” (v. 35). Here it indicates the privileged situation in which it is possible to manifest gratuitous love. Here we touch the pinnacle of Christian ethics.

The proposal of Jesus was prepared by some texts of the Old Testament: “If you see your enemy’s ox or donkey going astray, take it back to him. When you see a donkey of a man who hates you, falling under its load, do not pass by but help him” (Ex 23:4-5; cf. Lev 19:17-18,33-34). Even the wise pagans gave similar advice. We remember those famous ones of Epictetus: “One needs to be beaten like a donkey, and while being beaten, he loves as father of all, as a brother the one who strikes him;” and Seneca: “If you want to imitate the gods, do good also to the ungrateful, because the sun also rises on the wicked.”

Apparently the statements of the aforementioned Stoic philosophers seem identical to those of the Gospel; in reality, they are dictated from a radically different perspective. “Do good to them and lend where there is nothing to expect in return” suggests Jesus (v. 35). And this recommendation excludes all seeking of one’s own advantage, even spiritual. Unlike that of the Stoics who were not acting for the good of others, but aiming for the achievement of inner peace, of imperturbability, of complete self-mastery, the disciple does not allow himself to be touched by any selfish thought, any complacency, any search for personal gratification. He does not even think to accumulate merit for heaven. He loves and gives in pure loss.

What reward will those who are led by this selfless love receive?

“It will be great!”—Jesus answers. Will they have a better place in heaven? No, much more: “They will be children of the Most High; for he is kind to the ungrateful and the wicked” (v. 35). This will be the prize: the similarity with the Father, his very own happiness, experiencing, already on this earth, the ineffable joy that he experiences in loving without expecting anything in return. The passage ends with the exhortation to the members of the Christian community to make visible in people’s eyes, the face of the heavenly Father (vv. 36-38).

In the Old Testament, God presents himself with the following words: “The Lord is a God full of pity and mercy, slow to anger and abounding in truth and loving kindness” (Ex 34:6). Mercy—the first of his features—is not to be identified with compassion, forbearance, forgiveness of injuries. Merciful—in biblical language—means being sensitive to the pain, misfortunes, and needs of the poor and the unfortunate. God does not just feel this emotion but intervenes performing deeds of love and salvation.

Jesus invites his disciples to cultivate feelings and to imitate the actions of the Father who is in heaven. With two prohibitions (do not judge, do not condemn) and two positive warnings (forgive, give), he also explains how to imitate the Father’s behavior. Those who are in tune with the thoughts, feelings, behavior of God do not pronounce sentences of condemnation against the brother. The Father—who knows the inner hearts—does not do it and will not do it even at the end of time. Those who have a piercing look like the Father, those who see a person as he sees it, condemns no one, is moved only by mercy before one who does wrong (Hos 11:8) and is committed in every way to get him or her back to life.

Consequently, we could summarize the message of the Gospel by saying that there are three categories of people: on the lowest rung are the wicked (those who, while still receiving the good, they do evil); higher are the righteous (those who respond to the good with good and evil with evil); finally there are those who respond to evil with good. Only they are the children of God and they reproduce in themselves the behavior of the Father.

by Fr. Fernando Armellini

https://sundaycommentaries.wordpress.com