Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

Sunday, November 19, 2023

November 20th 2023 is the first anniversary of the beatification of Father Ambrosoli, which took place in Kalongo on November 20th 2022. A significant anniversary, if you consider that Blessed Giuseppe Ambrosoli was the early incarnation of what can be considered a leap forward in conceiving the unitary content of evangelisation, that is, its constitutive ratio (announcement of Christ and integral liberation) and the articulation of doing mission (two realities which, despite their distinction, cannot fail to imply each other).

Indeed, what kind of evangelisation would it be that did not place Christ as an absolute priority and, at the same time, relegated justice, and human development to simply optional consequences? The fact is that, often, our distinction between the two realities has meant a separation in practice.

Yet, the Synod of Bishops of 1971, in the final document, entitled Justice in the World, states that “acting for justice and participating in the transformation of the world clearly appear to us as a constitutive dimension (ratio constitutiva) of the preaching of the Gospel, that is, of the mission of the Church for the redemption of the human race and the liberation from every oppressive state of affairs” (Final Document, 6). And again: “The mission of preaching the Gospel, in our day, requires that we commit ourselves to the total liberation of man already in his earthly existence” (Ibidem, 37).

Even the Apostolic Exhortation of Paul VI Evangelii Nuntiandi (1975) reiterated this close connection, stating that “it is impossible to accept that in evangelisation we can or should neglect the importance of the problems, so debated today, which concern justice, liberation, development, and peace in the world. It would be to forget the lesson that comes to us from the Gospel about love for our suffering and needy neighbours” (EN, 31).

Ambrosoli, as a priest and a doctor, kept the two realities closely united, without having to sacrifice either the doctor or the priest, knowing how to translate into practice the relationship of an intimate connection and mutual dependence between them. It was the first example of a successful symbiosis among our members. The doctor reached the patient’s soul and the priest took on a more concrete humanity radiating closeness, respect for others, a desire for transformation and responsibility.

By quickly scrolling through the biography of Blessed Ambrosoli, we will try to grasp some elements that qualify his person and the key moments that required him to make decisive choices. We will therefore look at some essential data which, although sparse, highlight the human and spiritual quality of the witness. In general, it must be said that in Ambrosoli, it is immediately clear that the God he believes in is pure love that tends to focus on the person and their humanity, to alleviate their pains and take care of their needs, restoring them to their full dignity. For Blessed Ambrosoli, only God and the needy person before him exist. This priority reveals that, not simply out of a certain natural inclination, he always takes a step back to create space for the other. Therefore, the priest-doctor, as an evangeliser, is no longer worried about protecting his image and his work, nor is he bothered by wanting to defend himself. What is striking about him is that this constant structural human discretion, placed at the service of divine love and supportive human love, is recognisable from the time of his youth and applicable to his entire life.

Biographical references

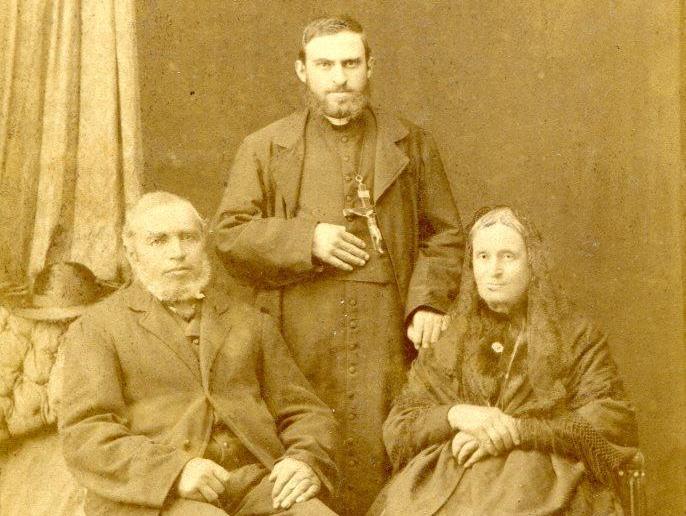

- From joining the Comboni Institute to the priesthood (1951-1955)

Giuseppe Ambrosoli came among the Comboni Missionaries with a robust educational path that had shaped him and, at the same time, made him capable of accepting further development. Without forgetting all he had received and without arrogance regarding his professional preparation, a person devoid of rigidity or closure, he remained open to acquiring the content of the Comboni formation which allowed him to refine his human and spiritual qualities and to exercise his medical profession with creativity and autonomy.

When, on 18th October 1951, Giuseppe Ambrosoli entered the Comboni novitiate in Gozzano (Novara, Italy), he was 28 years old. He had already an educational and professional experience behind him that shaped him for life: first the ‘Cenacolo’ in Como (1945-1950), then the faculty of medicine of the state university of Milan (1946-1951), amounting to a spiritual, academic, and ecclesial hinterland. The spiritual horizon that the Cenacle proposed was heroism. Mario Mascetti, his companion at the time of the Cenacle, writes: “He never unplugged the circuit of grace, as if he had developed the habit of verifying every moment (today we would say in real time) the conformity of his actions with what pleases to God”. A spirituality, however, that is continually challenged by reality. In the very hot weather of the 1948 election, Giuseppe wrote: “It is not enough for others to call me a Christian Democrat; they must feel the influence of the Jesus that I carry with me; they must feel that in me there is a supernatural life that is expansive and radiating by its very nature.”

Even university studies, despite all the commitment and rigour they demanded, in the light of this embodied spirituality, were freed from future personal and material benefits: “Putting myself in the apostolate among the poor with humility, becoming like them, on their level, loving them, taking an interest in them.” It is not only a clear option for the poorest, but also an option made within the ecclesial community, which translated into the ability to operate in a group. He wrote to his friend Virginio Somaini, like him a delegate of Catholic Action in the parish of Cagno (Varese), recognising their single origin: “Both of us are called by the Lord to give Him glory in the field of Catholic Action; let us collaborate, living together in prayer and in Grace, in using our talents, in making this obvious preference of God fruitful. Let’s work together, dear Virgil in the A.C.! On Sunday morning, during the conference, I will have the consolation of being able to think that another young man like me, with whom I am united in love for Christ, is doing the same work as me for the same ideal!”

Ambrosoli was, to all intents and purposes, like an unstoppable diesel engine. In fact, on 18th July 1949, he defended his thesis in medicine, and at the beginning of August, he was at the Comboni house in Rebbio (Como), asking for information. Reassured that he would be able to practice his medical profession in the mission, he left for London to attend the course in tropical medicine lasting until August 1951. On 5th September, he wrote to the superior general of the Comboni Missionaries, Father Todesco, asking him to be allowed to enter the Institute and on October 18th, he was already in the novitiate at Gozzano.

The future horizon of the mission allowed him to face the narrow environment of the novitiate and to be able to fit in among fifty-one young people, most of whom were aged between 17 and 19, accustomed only to the restricted clerical environment. Giuseppe, accustomed to the more complex diocesan world and the secular environment of the university, grew spiritually, maintaining his acute and autonomous spirit, aimed at the mission. His inner spirit, the mission, professionalism, and community were the pillars of his world. Giuseppe never played at being the emerging one, the one ‘outside the group’, or at feeling – or disguising himself – as the different one, the more prepared one, the superior one due to family ancestry or experiences acquired in various fields. He is someone who knows how to fit in cordially, despite initial difficulties, first in the novitiate community, then in that of the scholasticate (1953). He studied theology in the Venegono scholasticate, continuing his medical practice in the nearby hospital of Tradate and carrying out frequent duties as “the medical officer” in the large community.

To Dr. Aldo Marchesini, who went to Kalongo in 1970 to practice surgery, he confided that it was the surgeon Angelo Zanaboni who taught him all the essential things in a year but hastened to add: “But the opportunities to learn continue throughout life. You can learn from everyone, even non-medical staff.”

Feeling a living part of the community – a brother among brothers – he convinced the superior of the scholasticate, Father Giuseppe Baj, a rather tight-fisted person, to let him install the heating system in the refrigerator-like house of Venegono castle, stating: “We must preserve the health of the future missionaries, even if we will no longer need radiators in Africa!” Dr. Tettamanzi Folliero, who met Giuseppe while he was in training at Tra-date hospital, remembers him as being very dedicated in attending to the confreres for whom he had recommended admission to the hospital, in particular towards a rather eccentric African bishop who made exorbitant demands. To the complaints of his colleagues, Father Ambrosoli replied with a smile and a simple phrase: “Our livery is charity.”

Among the many qualities shown by Father Ambrosoli as he prepared for his future missionary service – and which today are required and seen as essential – some emerge clearly: a strong sense of community, a great willingness to offer any service, remaining ‘in the background’, the desire to offer professional services, always seeking the best solutions. Ambrosoli anticipates in practice what he would afterwards say to Sister Enrica Galimberti, his assistant at Kalongo Hospital: “Try to do things perfectly. However, if they turn out well, don’t tear them apart to make them perfect: you would ruin them. Just be happy that you have done them well. However, always seek perfection.” A concept that is neither pietistic, moralistic, or superficial, but of a purely altruistic nature: to be able to give the best of oneself, one must continually prepare.

- A lifetime in the mission – Kalongo (1956-1987)

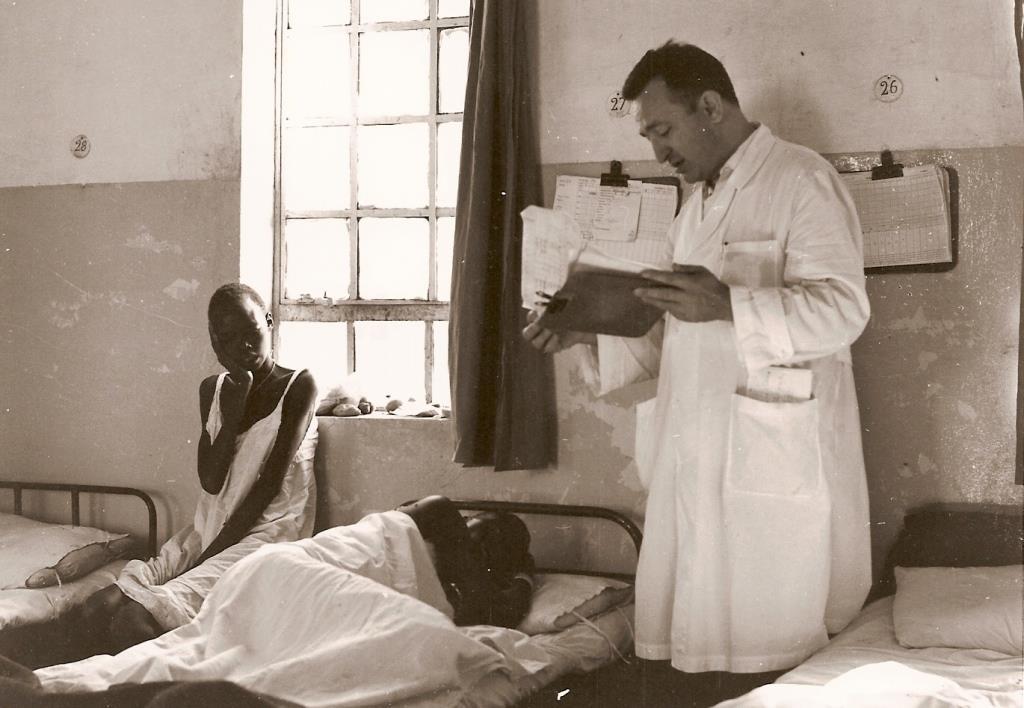

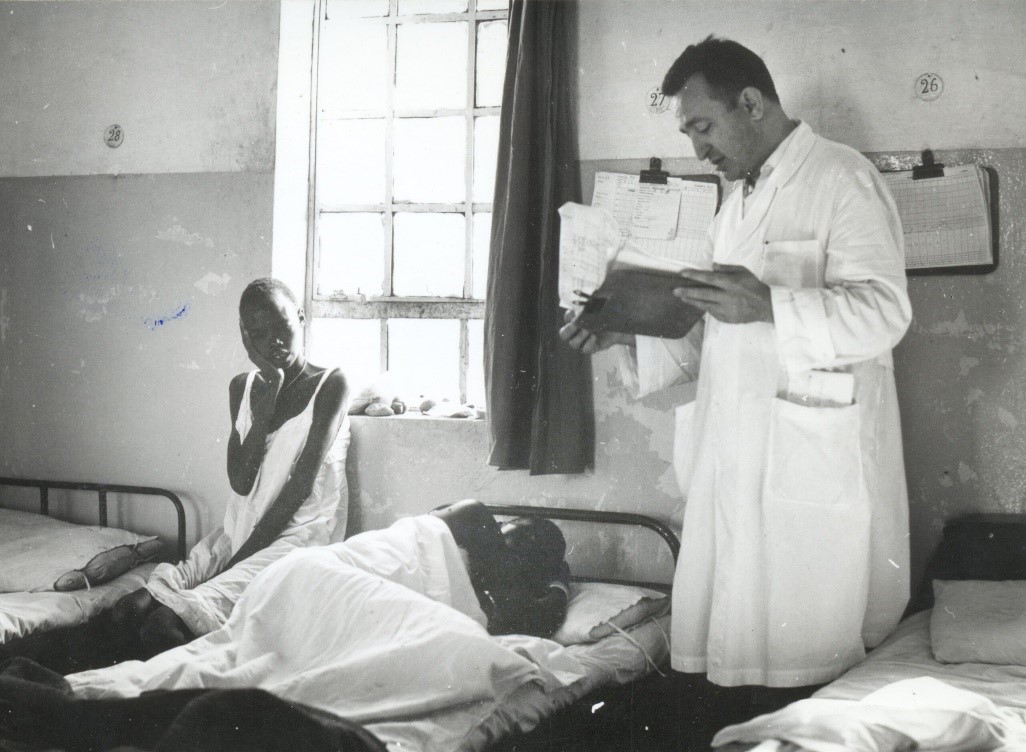

The priest and doctor Ambrosoli arrived at the mission at the age of 33, with a great human, spiritual and professional background. He has already given a good account of himself in the novitiate and scholasticate, but it is in the years of mission that he appears in all his splendour. For 31 years, always in the same place, from 19th February 1956, when he set foot in Kalongo Hospital for the first time, until the tragic evacuation of the institution to which he gave his all, on 13th February 1987.

In Kalongo, he found a Comboni confrere and a Comboni Sister of great ability: Father Alfredo Malandra and Sister Eletta Mantiero. Thanks to them, the first dispensary had already developed into a proper maternity unit. With the arrival of a doctor, the dream of a School for Midwives began to take shape. Ambrosoli is therefore part of a pre-existing structure and will bring it to full efficiency in terms of personnel and operations. St. Mary’s Midwifery School will become the flagship of the entire Kalongo hospital structure, even at the cost of his own life.

The beginnings were anything but easy: the first task was to bring all the dispensaries in Northern Uganda (Aber, Padibe, Nyapea, Moyo and Angal) up to standard and to find a doctor, who specialised in obstetrics and gynaecology in England, to obtain from the government British – favourable but only verbally – the approval of the School for Midwives. A series of names followed one another in those years, marked by an equally long series of hopes and bitter disappointments: the Polish doctor Lydia Wlosczyk; the couple of Remotti doctors from CUAMM (University College of Aspiring Missionary Doctors, now Doctors with Africa) from Padua; Scottish doctor Jane Mac Shane; Dr. Pietro Tozzi; Dr. Morelli; the Dutch doctor Bonnar; a doctor from the Persian Gulf; Dr. Doyle, etc.

Gradually, the hospital was taking shape and expanding, until it reached a capacity of 200 beds. In the meantime, the fame of Aiwaka Madit (‘great medicine man’) or Doctor Ladit (‘great doctor’) was growing and spreading throughout Uganda and even abroad, reaching Kenya, Tanzania, Zaire, Ethiopia, Sudan, and even India.

The political events which with the independence of Uganda in 1962, should have ushered in a time of peace and development, instead weaved a tapestry with a background that was all too changeable and often dramatic. In 1963, all primary schools were nationalised. In January 1967, ten missionaries were expelled, accused of having maintained contact with the liberation movements of South Sudan and of having spread false information about the Government of Kampala, which they accused of secret agreements with that of Khartoum for the elimination of the rebels. In 1972, there was the further expulsion of another six missionaries for lack of legal documentation. In July of the same year, entry visas were denied to new missionaries, doctors, nurses, and teachers. At the end of the year, another 50 missionaries had to leave the country. In June 1975, there were further expulsions of 16 missionaries, chosen “surgically” in crucial positions.

Meanwhile, despite the uncertainty, Ambrosoli continued to expand the hospital. At the end of 1972, he began the construction of a new surgery department, replacing the four houses that made up the old department, managing to complete the work in May 1973. The surgery department now had 67 new beds. Other buildings were erected at the same time: a large classroom for practical demonstrations, a spacious 13-meter-long warehouse, a beautiful refectory to accommodate 25 unqualified girls working in the hospital, 6 small closets, the central medical department, and others. Work was also under way on a large reservoir on the rocky spur overlooking Kalongo.

Father Ambrosoli began to wonder whether, given the difficult conditions in which Uganda found itself, all that constructive activity might seem mere folly. Slowing down the pace a little would be a plausible hypothesis, but he immediately rejected it as he was working only for the glory of God and for the good of the people. He knew perfectly well – like everyone else – that Kalongo Hospital was the only healthcare facility within a 70-kilometre radius. To the Comboni Sister, Dr. Donata Pacini, who pointed out to him that expansion necessarily would involve an excessive amount of work, he replied frankly, leaving no room for disagreement: “The sick need it.”

The 1973 statistics show how much the sick took possession of Father Ambrosoli’s life: outpatient visits, 44,946; admissions, 5,488; deliveries, 885; prenatal visits, 1,810; operations, 632; x-rays, 1,128; laboratory tests, 37,421. Father Giuseppe himself it was who performed almost all the operations or supervised the other doctors, teaching them his techniques, while supervising the new arrivals making sure everything went smoothly.

The secret source

Where does one find the strength to carry out all those activities and the courage to continue in such difficult times? Certainly, Father Ambrosoli certainly had extraordinary managerial skills. However, the source of his audacious and exuberant activity must be sought elsewhere. In April 1973, in a letter to friends of Caritas in Bologna, he wrote: “It seems to me that this is precisely the right moment to show that we are not working for our own interests. It seems to me that this is not the moment for us to ask for economic aid, but rather the moment to ask for spiritual aid, so that the Good Lord may save Ugandan Christianity.” Ambrogio Okulu, an Acholi member of parliament, would later write about such dramatic times in a posthumous re-enactment: “Arriving in 1956, he [Father Ambrosoli] experienced 6 years of political struggle led by the Ugandans to gain independence from the English. Later, he lived under the first dictatorship of Obote and the military dictatorship of Amin. [...] All these adverse conditions led Dr. Ambrosoli to commit himself all the more and earned him the esteem of those who hated the missionaries. […] In the upheavals in Uganda at the time, Dr. Ambrosoli faced religious zealots, vengeful politicians and undisciplined army officers with the same courage. When faced with them, not once did he take a step back out of fear.”

Father Giuseppe refused to give in and continued along this line, because his deeds were dictated by certain unshakable principles. In a letter to Prof. Canova of the CUAMM, he lists three that he considers fundamental: “The first, and most important, is the spirit of Christ, consisting in the determined will to work for the spread of the kingdom of God; the second, the spirit of sacrifice, and the third, good technical preparation.” Certainly, he recognises that surgery “also has a clear psychological influence on people who compare it with the ineffectiveness of local healers”. However, the fixed point from which everything must start and to which everything must submit is a statement written in September 1957, just over a year after arriving in Kalongo: “I must try to ‘impersonate’ the Master when he treated the sick who came to him.” A Christological faith that has already marked his life as a university student responsible for the youth of Catholic Action in Uggiate. Already during that period, he wrote to a friend: “The precious time that we dedicate to the CA has, at all times, a supernatural purpose, and there is no danger of losing ourselves in vain things, because this work brings us ever closer to Him, the Christ!” The Polar Star, therefore, was Christ, present in the hardest moments, who led him to the central formulation of his evangelising action: “God is love. Where there is a neighbour who is suffering, I am his servant.” No mere catchphrase but a concretisation of what he wrote in his ‘Book of the Soul’ (diary): “I must seek You alone, and ‘in Cruce’ (on the Cross)”; «we must enter the circle of the Trinity […] and get a little closer to Jesus on his way of the Cross”; “[I want] to accept being disturbed,” that is, like Jesus, to live with others, under others, and for others. Ambrosoli immediately makes it clear that he does not intend to let the multiplicity of his works become an external vortex, visibility at all costs, a whirlwind that would overwhelm him in its intoxicating coils and, in the end, make him a slave to himself and his self-image.

Sickness (1982) and the evacuation of Kalongo (1987)

It is surprising how Father Ambrosoli manages so naturally to combine a spiritual life, characterised by essentiality and simplicity, and a surgical service that is increasingly demanding in terms of performance and skills. In this sense, the encounter with the spirituality of Charles de Foucauld illuminates his path, and so the path undertaken as a young man deepens and brings him ever closer to the historical Jesus, opening him to ‘the prayer of abandonment’ and to the acceptance of de Foucauld’s ‘beloved failure’. He writes in his Spiritual Exercises notebook: “It remains that I must continue in the effort to experience the presence of Jesus in my heart and frequently ask myself what he would do in my place.” He confides to his friend Piergiorgio Trevisan: “The only disappointment is that, when I ask someone if they have noticed that I have changed for the good, I hear them say ‘no’! In any case, I live much happier than before, even if there is more sacrifice. […] I always thank the Lord that there is so much work, because we are here precisely for this, and it is through medical work that we can reach the souls of many sick people. In these countries, pastoral care always passes through the body. It seems strange, but that’s how it is.”

These are sacred statements that will come back to his mind in December 1982, at the time of the humiliating blow of his renal disease (one kidney atrophied and the other seriously compromised, with renal function reduced to 30%) and during the calamitous years after Amin which dramatically changed the history of Uganda. Chronologically: the time of Obote’s second government (17th December 1980 to 27th July 1985), the brief interregnum of Bazilio Olara Okello (27th July 1985) and General Tito Okello (29th July 1985 to 26th January 1986) followed by their dismissal, and the entry onto the scene of Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, with the occupation of Kampala (26th January 1986) and the progressive ‘liberation’ of Uganda. What remained of the Okelo army fled either towards the North or South Sudan. Others hid their weapons and remained in their homes to wait for events to develop. Naturally, after the retreat and defeat, the vanquished indulged in looting and murdering people from the south of the country. In the northern regions, tribal hatred was growing. Not even the missions were spared. In a diary written by the Fathers in Kitgum we read: “What saddens us and the people most is that the looters are from our own tribe: ‘They are our children’, they say dejectedly”. There is a climate of great confusion and fear, while we wait for government troops to arrive to re-establish a modicum of order and bring some peace. Even in Kalongo, conditions are dramatic, to the point that Father Ambrosoli writes: “1986 was the most difficult year of my thirty years in Kalongo.”

The dreaded epilogue – the order to evacuate Kalongo Hospital – arrived on 30th January 1987. On 7th February the peremptory order was given to prepare to leave. On the 13th, 16 trucks arrived. A convoy was formed: 34 cars and trucks, with 1,500 soldiers and civilians. Behind them, we leave the warehouses prey to flames which reduce food and medicine to ash. Of all the hospital material, only 20% could be taken.

The superior general, Father Francesco Pierli, writes a moving letter to Father Ambrosoli. Among other things, we read: “For all of us, Kalongo Hospital was much more than just a hospital. It was the sign of this passionate love for the people, of this taking on the wounds of the people which constitutes the most beautiful nucleus of our vocation. […] I make your words my own: ‘The heart suffers, but faith and hope render everything tolerable’.”

The torment experienced does not kill hope: that exodus of people - missionaries, men and women, doctors, sick people, and obstetrics nurses about to take their final exams for qualification - is the extreme act of love and identification with a people and with a work. This explains Father Ambrosoli’s decision to be buried in Africa, next to his hospital. This also explains why he wanted, at the cost of his life, to save the School for Midwives to guarantee official exams for the girls who had been preparing for them for so long. This helps us to understand how the words he whispered as he died in Lira are to be considered the final point and the unequivocal revelation of what moved and energised his entire life internally: «Lord, may your will be done, even if it were a hundred times…!”. It was 1.50 pm on Friday, 27th March 1987, when, still in the front line, he passed away at the age of 64.

This was the conclusion of a spiritual experience that had reached its peak, having revealed a strong and profound sense of God’s loving plan throughout his history as a missionary. There is a clear sense of the ‘hour of God’, in the awareness that in it every thought, every effort, and every human project finds its right place and solution. We are faced with the highest moment of union with the invoked God and the fullest expression of love towards brothers and sisters, now left to pursue their own freedom and autonomy. Father Ambrosoli definitively seals in death what he has always been in life: ‘a person among people’.

His whole life in Uganda was marked by this double movement of empathetic faith towards the person next to him and of medical service offered with total gratuity. For Ambrosoli the missionary, a professional service that elevates, cares and saves cannot be provided without a profound love for the person; nor can one show authentic empathy without striving to give the best of oneself professionally.

In his life, we see the fundamental aspect of the ecclesiology of the Second Vatican Council realised: «The Church is, in Christ, in some way the sacrament, that is, the sign and instrument of intimate union with God and of the unity of all human race” (Lumen Gentium, 1). An ecclesiology that is more relevant today than ever: the mission of the Church is accomplished, rather than with the implementation or improvement of structures, with the recognised primacy given to human relationships and experienced concretely in them. These relationships, in turn, will push the Church towards the right relationship with the world and society and will lead it to respond with courage and creativity to the stresses and changes of today’s changed situations.

Indications from the life of Father Ambrosoli on how to be evangelisers today

Let us now move from Father Ambrosoli’s biography to some values that made his life an evangelising testimony. We find there an astonishing consonance with the reading outline that Pope Francis offers in the apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium – On the Proclamation of the Gospel in Today’s World. In the fifth chapter, Francis indicates a set of values that constitute many operational lines for a current mission (EG, 250-274). In practice, you cannot carry out a mission without development or inclusion in a community project and without a set of values that give consistency to the person and the group.

- “An outgoing Church” – Opening oneself to diversity

In Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis insists greatly on the need for the Church “to learn to accept others in their different way of being, thinking and expressing themselves. With this method, we will be able to assume together the duty to serve justice and peace, which must become a fundamental criterion of any exchange” (EG, 250). Having affirmed this basic attitude, which consists in the ability to break away from pre-packaged patterns and in the urgency of equipping oneself with a spirit of openness to narrate “the greatness of God” (EG, 259), Francis invokes the Holy Spirit: “I pray that he may come to renew, to shake, to give impetus to the Church in a daring exit from itself to evangelise all peoples” (EG, 261). This “coming out of oneself”, attentively listening to situations, is a gift and a characteristic that makes it possible to identify an action as an action of the Spirit.

Ambrosoli is a witness par excellence of this open-mindedness to diversity, a particularly compelling example.

In 1944, during his training in Germany, young Giuseppe found himself with medical students destined for future positions in the sadly notorious Social Republic of Salò. In an ideologically hostile environment, he could withdraw into his own little world. Instead, he stands out for his concept of pure service in his medical activity, for his great respect for the adverse opinions of his fellow soldiers, for the sense of moderation and conviction with which he expresses his religious belief, and for his ability to open spaces of serenity and encouragement in a demotivated and at times violent habitat. Camillo Terzaghi, his barracks companion, writes: “The soldier Giuseppe Ambrosoli already showed a profound theological knowledge from the beginning, and the comrades wondered what political faith he belonged to. However, even in discussions with the most ardent atheists, he was conciliatory, bringing his contribution to knowledge, not being scandalised by contradictions, and revealing the principles of love and brotherhood. Naturally, due to his angelic calmness, he was respected and considered, while the other believers, due to their intransigence, were harshly attacked and even offended.”

Doctor Luciano Giornazzi, also a fellow soldier of Giuseppe and of a political faith that was anything but favourable to the Church, could not help but note with admiration the union of life and word in him, which, however, always went beyond the purely existent, whether it be his personal gain or the ideal or ideological boundaries of belonging. Giornazzi writes: “There he was, once we had consumed our meagre rations, retiring to his straw mattress, and reciting a few prayers out loud in almost total indifference. There he was, ‘reprimanding’ some of us who cursed the bad luck that brought us, willy-nilly, to that damned place. He had a good word for everyone, and, in the end, he managed to calm the anger, the pain, and the anxiety. I remember him during a training march (15 km!) when in addition to his own, he carried my backpack as well since I was unable to walk due to a sudden pain in my knee. I also remember him when, while I was lying in the ‘infirmary’ (as they called it) with a high fever and unable to move, he brought me my rations twice a day, always with a smile on his face and always with some words of encouragement (He did all this for about a month). To cut a long story short, during that period Ambrosoli was always available to everyone and was always a good example for everyone. He was different from us. He had an edge, moral and material, which certainly came from his permanent serenity.”

In 1946, in a time of great polarisation of ideas and parties – and therefore, generally a time of great opposition and exclusion – Giuseppe, a convinced and active militant of Catholic Action, left the pure confessional barriers to existentially constitute a platform for dialogue, understanding and of testimony to values lived without proselytism, but, at the same time, without pretence. What he is, is what he lives, opening ever wider spaces of understanding and collaboration. He wrote in his notebook from 1947: “The apostolate in the family is very important and I must dedicate myself with determination, banishing human respect. The environmental apostolate: at school, in hospital. It’s not enough that others call me a Christian Democrat; they must feel the influence of the Jesus that I carry with me; they must feel that in me there is a supernatural life that is expansive and radiating by its nature... I must love the poor and not fear being with them. I must get down to their level and bring them a good word. For me, the apostolate must not only be local but must also take place among the humblest social classes, the poor, regardless of whether they are workers rather than students. To put myself in the apostolate among the poor with humility, to be like them, on their level, to love them, to take an interest in them.”

However, it is in mission where diversity becomes a stimulus for Ambrosoli to move from understanding to acceptance and to change. Ambrosoli is someone who, while accepting what exists, is not satisfied with what exists. Finding himself with two strong personalities, such as Father Alfredo Malandra and Sister Eletta Mantiero, the two pillars of the Kalongo mission and its structures, room to manoeuvre for him as a novice doctor of all things African must have seemed very limited, if not downright disappointing. To survive, he could have claimed far superior medical training and thereby been the cause of irreconcilable tensions. Instead, he fitted in, bringing to full flower what was unconsciously the profound desire of the two elderly missionaries. In Kalongo you are not defeated in your own ideas, because it is impossible to hold your own before someone greater, but you are gradually transformed. Dreams, then, become reality: Sister Mantiero’s modest Savannah maternity unit develops into a hospital with 350 beds, and a servile female situation is redeemed in a School for Midwives known nationwide and persistently dreamed of by Father Malandra. We may even compare Ambrosoli to an elephant who knows how to tread among items of glassware. The mission often forces great projects and fragility to coexist.

The ‘little hospital in the woods’ – as Ambrosoli called it –, which had grown surprisingly over the years, did not look out of place even in comparison to Lachor Hospital in Gulu, the hospital in the capital and therefore more central and subsidised by the government. The 1979 annual report of the Diocese of Gulu allows for a useful comparison: 5 doctors work in Kalongo, one of whom is completely dedicated to lepers, while 7 doctors work in Lachor, one of whom is Ugandan; there are 14 nurses in Kalongo and 13 in Lachor Hospital; there are 62 midwives with courses in Kalongo, 63 at Lachor Hospital; hospital beds 323, at Lachor Hospital 220; maternity beds 75, at Lachor Hospital 34; in Kalongo there were 113,661 outpatient visits compared to 39,735 at Lachor Hospital; in Kalongo the major operations were 1,012, at Lachor Hospital 732; in Kalongo 1,379 deliveries, at Lachor Hospital 701.

The School for Midwives was the flagship, the creation so greatly desired and cared for by Father Ambrosoli. From 1961 to 1978, the hospital produced 245 regularly registered midwives (enrolled midwives), of whom 65 from 1961 to 1967 and 180 from 1968 to 1978. Given the exceptional results, in 1979, the Ministry of Health approved a new Course for Midwives at a higher level, which however, due to the war, could only begin in 1980. Nevertheless, the School for Midwives, in its 30 years of activity, would produce 400 graduated professional midwives, 40 of whom held the rank of head nurse (registered midwives).

Ambrosoli, already at this first level of ‘the bold exit from oneself’, asks us the question if in our being and carrying out mission there is this mental openness to think beyond what exists, with the healthy realism of wanting to make it grow with the contribution of those who were before us and those who will remain after us. Ambrosoli stimulates us to grasp which are the fields of presence and action where change is most urgent today. This is exactly the opposite of those who give up thinking and entrench themselves in self-defence, in sterile recriminations, in the progressive not seeing, not hearing and not questioning themselves. Ambrosoli asks us unavoidable questions on which to base many of our reflections and changes of pace in the mission: what are the significant mission experiences among us currently? What are the experiences, following a project with a history, with options made and tested through periodic discernments and assessments? His options are still there, in front of everyone.

b. Neither disembodied spirituality nor soul-less action

The second aspect of “evangelisation according to the Spirit” is living it and proposing it as a total commitment, keeping contemplation and action closely united, that is, contemplation in action and vice versa. “Mystical notions without a solid social and missionary outreach are of no help to evangelisation, nor are dissertations or social or pastoral practices which lack a spirituality which can change hearts” (EG, 262), Pope Francis writes. And quoting from Novo Millennio Ineunte by John Paul II, he adds: “We must reject the temptation to offer a privatised and individualistic spirituality which ill accords with the demands of charity, to say nothing of the implications of the incarnation” (ibidem). Separating the two would mean the emptying of the meaning of action and falling into intimacy and individualism.

In the time in which he lived his missionary service, Ambrosoli certainly contributed to fully inserting the medical service into evangelising practice, which then was above all understood almost exclusively as the announcement of the Word and the celebration-practice of the sacraments, in view of the foundation of a local church. Without questioning this basic option, Ambrosoli contributed to broadening the concept and reality of the announcement by offering his medical professionalism. Service to the sick as he experienced it has become a way of evangelical proclamation, as noble and necessary as preaching. This is demonstrated by his rigorous vocational discernment, maintaining the practice of medical activity and pastoral commitment; the decision to choose the Comboni Missionaries, for the priority missio ad gentes, unlike the first choice of the Jesuits; the interior clarity of his pronouncement; the decision on the steps taken; the concrete deadlines inserted into a prayed for, reflected on, implemented global process or framework. Ambrosoli was not the type for hasty decisions and fleeting enthusiasms nor for action without reflection or reflection without action. Belief and practice constituted the dual aspect of his decisions. The action was reflected in internal values cultivated, examined and contemplated for a long time (the result of an internal discipline, of demanding prayer times, of spaces and times characterised by effectiveness and efficiency, of constant deepening of specific virtues such as service, availability, understanding, humility, etc.) and, on the other hand, this internal reflexivity and seriousness sought their authentication in a practice developed in common and pursued with consistency, method and rigour.

In his notes taken during the Spiritual Exercises of 1974, he wrote: “If only they could see Jesus in me! It’s not about doing different things, but about the way to treat the sick. They must feel that the contact is fraternal through the charity of Christ.” And, in fact, fraternal contact can only transmit Christ’s concern if it is a specific service – in our case, medical – which makes use of everyone’s contribution, takes place through careful pre-paration and competence, and is carried out in a relationship empathetic with the patient, and it, therefore, combines respect, attention to the person and rigorous technicality.

Dr. Augusto Cosulich, from Pordenone, in Kalongo from 1983 to 1985, wrote: “What I learned most from Giuseppe was his efficiency in the operating room, not giving importance to the elegance of the surgical gesture, to the fact that the light on the operating field is not the very best or that whoever helps you does not do so in the best way. He was used to carrying on, even if perhaps there was a little bleeding or if the patient was not perfectly relaxed. His motto was to obtain the maximum result for the patient with the minimum waste of resources (always relatively scarce in Kalongo). He was able to do this thanks to his enormous experience which, combined with his professional skills, allowed him to immediately understand what the problem was as soon as he opened the patient’s abdomen (it must not be forgotten that in places like Kalongo, it is still the practice, and will continue to be so for a long time, to make a diagnosis at the time of surgery, the famous open and see), decide what to do, and carry it out as quickly as possible so as not to use up surgical material or anaesthetic drugs any more than necessary. From this point of view, he sometimes even exaggerated: he could reuse gauze soaked in blood several times after having wrung it out in a basin; he used suture threads so parsimoniously that he would have been a great example for all those Italian surgeons who were so easily wasteful with public hospital materials. They tell me that, in previous years, when there was no one who could take care of the anaesthesia, he himself practised spinal or epidural anaesthesia (for the latter he had also devised a modification compared to the classic needle insertion technique) right before going to don sterile garb to begin the surgery itself. He also demonstrated considerable practical sense and prudence, always with a view to being useful to the patient and minimising hospital costs [...]. He was a patient and very valid teacher, he sincerely loved to teach everything he knew, including the ‘tricks’ and all those little tips that made the difference between a normal surgeon and a great surgeon, which he was.”

In the life of the evangeliser, closely connecting the human aspect of the relationship and professionalism, both in the medical and pastoral fields, requires a refined balance between contemplation and action and their necessary correlation. True contemplation always leads to considering a problem to be solved or a need to be answered such as the needs of the person. The personal aspect, so evident in Father Ambrosoli, leads him even further to an extremely competent and accurate medical service. With his practice, he poses the problem of specific preparation: what type of preparation and planning do we currently guarantee when faced with the urgent needs of the mission? This involves the sort of training to be followed, the non-generic but targeted preparation, and the ability to integrate and collaborate in a common plan where any hidden personal compensation is banned. Ambrosoli makes us understand that a common project requires a consistent interiority, which, in turn, requires specific skills. Perhaps we should reconsider the relationship between provisionality, preparation and continuity, and humbly ask him to enlighten us!

The sources of joyful and enthusiastic discipleship

The credible evangeliser for our time can only be “a person who is convinced, enthusiastic, confident, in love” (cfr. EG, 266). Pope Francis identifies him as the one who is a seeker after the glory of God (the best protection of the good of the person and the defence to the bitter end of the defenceless and little ones), a man or woman of prayer (the necessary path to follow to struggle and obtain integral liberation). Francis writes: “It is about the glory of the Father, which Jesus sought throughout his entire existence” (EG, 267), and it is necessary to be «well founded on prayer, without which every action runs the risk of being meaningless and the announcement ultimately devoid of its soul” (EG, 259).

It would be enough to remember Ambrosoli’s very precious double legacy, with which we cannot help but compare ourselves and which was the common thread of his entire life: the breath of prayer and the sigh in death through the surrender of himself to the will of God. With the hospital evacuated, the school in a precarious condition and the probability of having to leave Uganda, before dying he whispers: “Lord, may your will be done, even if it were a hundred times!”. The God invoked is the God recognised as the protagonist of everything, of the present and of the future. The apparent failure, then, may well be called ‘the beloved failure’. And it can only be like this for someone who, from a young age, wrote: “The apostle is only as good as he prays”. And, as an accomplished surgeon, he repeated: “It is God who does the work. I know nothing!”, and on his deathbed he asked: “Help me to pray! I want to pray.” He often did exactly this with the sick, when he could no longer treat them, asking them to pray with him, involving the staff present in the operating room in prayer. Doctor Luciano Tacconi, present in Kalongo from 1978 to 1987, wrote: «In the most dramatic moments of an illness, our concern as collaborators was to hurry because we considered the time Father Ambrosoli used in preparing them for the ‘extreme step’ was time taken away from the patient. Instead, we realised that preparing a man or woman to accept death is also part of the doctor’s duties and reflects the respect that must be shown for the whole person: body and soul.”

With total adherence to the will of God and with prayer, doctor Ambrosoli transfigured his service into a salvific announcement. In him, what Pope Francis writes about a true announcer was literally realised: “Jesus wants evangelisers who announce the Good News not only with words but above all with a life transfigured by the presence of God” (EG, 259). Tempered by the mission, Father Giuseppe will come to summarise all this in his unforgettable motto: “God is love. There is a neighbour who suffers, and I am his servant.”

The question we must ask ourselves, both as individuals and as missionary communities, is inevitable: not so much whether we pray or who we pray for, but what is the quality of our prayer.

The experience of being a people

There is another necessary condition for being “evangelisers with the Spirit, that is, evangelisers who open themselves without fear to the action of the Holy Spirit” (EG, 259): “The spiritual pleasure of being a people” (see EG, 268-274). This condition can be summarised as follows: experiencing closeness and feeling spiritually close to people. These are words that have a tremendously concrete meaning. Closeness encompasses various nuances: ‘staying with’ when others flee; loving with the intensity of a passion that goes to the point of ‘suffering’; looking into people’s eyes; feeling the contact; experiencing space without self-defence; being present where things happen; going beyond appearances; etc. Only in this way “do we truly accept to come into contact with the concrete existence of others and know the strength of tenderness” (EG, 270), because “we acquire fullness [only] when we break down the walls and our heart is filled with faces and names!” (EG, 274).

Pope Francis offers here a significant sample of this closeness: “To be authentic evangelisers, it is necessary to develop a spiritual taste for remaining close to people’s lives, to the point of discovering that this becomes a source of superior joy. The mission is a passion for Jesus but, at the same time, it is a passion for his people” (EG, 268); like Jesus, if we talk to someone, “we must look into their eyes with a profound attention full of love... rejoicing with those who rejoice, weeping with those who are weeping; arm in arm with others, we are committed to building a new world “ (EG, 269); “Jesus wants us to touch human misery, to touch the suffering flesh of others... that we give up looking for those personal or community niches that shelter us from the maelstrom of human misfortune” (EG, 270).

Ambrosoli showed a unique ability to be with people due to the ease he had in creating relationships with everyone, the naturalness of his coexistence with the most disparate people and the generosity with which he showed himself available to every request. Patience and sense of service, promptness and self-forgetfulness, seasoned with his ever-present smile, indicated not only how much he felt in symbiosis with the people who revolved around the hospital, but above all they constituted that path of joy and serenity indispensable for feeling at one’s ease and growing together.

In his proverbial “patience” we touch the extreme frontier of the charity of the missionary doctor Ambrosoli: others were accepted with all their diversity: the sick African, the one simply seeking a favour or the doctor who came to Kalongo to gain experience in surgery. Sister Silveria Pezzali, who spent 14 years with him in Kalongo, often complained about his infinite patience and always received the same reply: “Understand, tolerate, forgive, and love.”

Many who knew him said of him: “It seemed like he had nothing else to do other than listen to the person facing him.” Instead, it was the daily application of an internal criterion he had espoused for a long time: “In order to love, I have to form a judgment of lovability about the person in front of me.” The ‘judgment of amiability’ was his livery in private and in public, with Europeans and Africans, with educated or illiterate people. In the eyes of simple people, this is a sensitive topic where it is impossible to cheat. Lino Labeja, a catechist from Kalongo, said: “I have never found a person as willing to listen as Father Ambrosoli was.” And Martino Omach, also a catechist: “He welcomed the poor, widows and orphans in a very particular way.” It is therefore not surprising that another catechist John Ogaba, in his deposition, felt the need to use the following admiring words: “From his way of welcoming people and entertaining them, advising them and encouraging them, one had the impression of meeting Jesus. He had great respect for everyone, but in particular for the poor and the abandoned.” In short, those who found themselves in difficulty knew they could count on Father Ambrosoli.

If, at a given moment, without losing his calm and composure, he is not afraid to reprove, even in public, an arrogant and violent brother of his, later he will have no hesitation in defending him publicly for having in turn been put down by a doctor.

The remarkable admiration for Giuseppe Ambrosoli was like his proverbial meekness, firmness, simplicity, and availability. He didn’t impose himself – he didn’t need it – but he attracted everyone.

Father Ambrosoli expressed his ‘joy of being a people’ in wanting to remain in Kalongo to provide his medical service, in wanting to die among his Acholi people and be buried like an ordinary poor man among his people.

God brought him to himself, and the Church ‘returned him’ to us, decreeing his exemplary nature and venerability. One year after the celebration of his beatification, we are invited to revisit the life and missionary attitudes of Blessed Giuseppe Ambrosoli, to know them, understand them, savour them and re-express them in our lives for the good of the mission and the Church.

Fr. Arnaldo Baritussio, mccj

Postulator General

Un anno dopo la beatificazione di padre Giuseppe Ambrosoli - francese

Un anno dopo la beatificazione di padre Giuseppe Ambrosoli - inglese

Un anno dopo la beatificazione di padre Giuseppe Ambrosoli - Italiano

Un anno dopo la beatificazione di padre Giuseppe Ambrosoli - portoghese

Un anno dopo la beatificazione di padre Giuseppe Ambrosoli - Spagnolo

Un anno dopo la beatificazione di padre Giuseppe Ambrosoli - Tedesco