Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

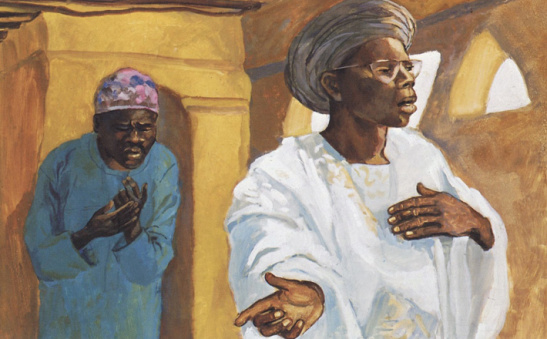

The parable of the Pharisee and the Publican usually awakens in many Christians a big rejection of the Pharisee who comes before God as someone arrogant and self-assured, along with a spontaneous sympathy for the Publican who humbly recognizes his sin. Paradoxically, the story could awaken in us this sentiment: «I give you thanks, my God, that I’m not like this Pharisee».

Luke 18:9-14

WHO AM I TO JUDGE?

The parable of the Pharisee and the Publican usually awakens in many Christians a big rejection of the Pharisee who comes before God as someone arrogant and self-assured, along with a spontaneous sympathy for the Publican who humbly recognizes his sin. Paradoxically, the story could awaken in us this sentiment: «I give you thanks, my God, that I’m not like this Pharisee».

In order to listen correctly to the message of the parable, we need to keep in mind that Jesus doesn’t tell it to criticize the Pharisee group, but to shake the conscience of «some people who prided themselves on being upright and despised everyone else». Among such we certainly find ourselves and more than a few Catholics in our day.

The Pharisee’s prayer reveals his inner attitude: «I thank you, God, that I am not like everyone else». What kind of prayer is this that believes oneself better than everyone else? Even a Pharisee, a faithful keeper of the Law, can live in a corrupted attitude. This person feels himself justified before God, and precisely for that reason, he becomes a judge who despises and condemns those who aren’t like him.

The Publican, in contrast, only happens to say: «God, be merciful to me, a sinner». This man humbly recognizes his sin. He can’t pride himself on his life. He gives himself over to God’s compassion. He doesn’t compare himself with anyone else. He doesn’t judge everyone else. He lives in the truth of himself before God.

The parable is a penetrating criticism that unmasks a false religious attitude that lets us live sure of our own innocence before God, while condemning from our supposed moral superiority anyone who doesn’t think or act like us.

Historical circumstances and triumphalistic tendencies that are far from the Gospel have made us Catholics especially prone to that temptation. That’s why each one of us has to read the parable in a self-critical manner: Why do we believe ourselves to be better than the agnostics? Why do we feel closer to God than those who don’t practice their faith? What is at the base of certain prayers for the conversion of sinners? What does it mean to notice the sins of others without living out our own conversion to God?

Recently, when asked a question by a journalist, Pope Francis made this affirmation: «Who am I to judge someone who is gay?». His words have surprised just about everyone. It seems that no one expected so simple and so evangelical a response from a Catholic Pope. However, that is the attitude of one who lives in truth before God.

José Antonio Pagola

Translator: Fr. Jay VonHandorf

https://www.feadulta.com

Gospel reflection

The narrator of the parable always sets a kind of trap to his listeners: he pushes them, without their being aware of it, to be in favor of one or the other personages of the story. Then, when they are fully involved, he draws the moral conclusion.

Reading today’s parable, one could lose the message because one risks to identify oneself with the wrong personage.

We are convinced of not having anything in common with the hypocrite, disagreeable, proud and presumptuous Pharisee. He despises others with arrogance and thinks of himself just, without being so in reality. Our sympathies are all for the Publican who, poor guy, did something wrong but has a golden heart. He repented and therefore merits love and understanding. We convince ourselves that this parable is addressed to those who feel aversion towards the Pharisee.

The parable is not that simple as it appears at first sight.

First, let us contemplate the Pharisee who, assuming the normal attitude (not proud) of a pious Jew, prays standing (which incidentally the Publican also does). No pretensions, no hypocrisy.

His monologue is a prayer and when he dialogues with God, opens his heart to him, he surely cannot lie. He says only what he feels. It’s enough to re-read attentively and without prejudices (vv. 11-12). Immediately we realize that we are faced by an upright, honest person of integrity. He observes faithfully the precepts of the law and avoids scrupulously all sins (thefts, injustices, and adulteries).

He does even more than what is prescribed.

The law orders to fast a day each year (Lev 16:29) and the Pharisee fasts twice a week (Tuesday and Thursday) for the reparation of others’ sins and to draw God’s blessings on the people. The law establishes that, during harvest time, the farmer gives immediately to the priests a tenth of the principal products: grain, wine, oil, firstborns of the flock (Dt 14:22-27). It deals with offerings destined to benefit the poor, to support the expenses of the temple and to form young rabbis. Unfortunately, the farmers—the Pharisee knows it well—are crafty and whenever they can, they do not fulfill this duty. To compensate for their possible (nay probable) theft, he pays tithing, of his own pocket, every time he buys their products. In short, he can serenely tell God: My Lord, there are so many wicked people in the world but don’t take it to heart, there are people like me who balance their misdeeds.

If one tries to look for something lacking in this man, one can hardly discover something reprehensible. He is proud of his righteousness, contrasts himself with other persons and distances himself from sinners. It is true that this creates a certain nuisance but no serious faults and then he has several reasons to feel better than others. There were people like that, honest, just, blameless. Let us forgive him a little pride.

Paul too, who strongly attacks the theology of the Pharisees, gives them the right of being zealous persons (Rom 10:2).

In a strident contrast with the first personage, the second, a Publican, appears on the scene. He has immediately attracted our sympathies for his humility. It is he who cheats us. It’s for something that he appears gentle and good-natured at first sight. He is a certified thief, a hateful exploiter, a jackal.

He does not extort money from the rich, bleeds the poor, and imposes exorbitant taxes on the most miserable among the farmers, who have not even bread to give to their small children. He has nothing good to offer to God. He is loaded with sins.

The law says that, to save oneself, he must give back all that he has stolen plus 20% interest and to immediately abandon his infamous profession. The conditions are so difficult to implement that the rabbis concluded that salvation is something impossible for the Publicans.

Now that we have clarified who the two personages are, on whose side are we? I hope that the sympathy for the Publican fades a bit and the aversion towards the Pharisee is being reappraised.

If this is the disposition of our spirit, let us conclude the parable in a meaningful and logical way.

Jesus would have liked to express himself more or less like this: the Pharisee should be a bit more humble. His contempt for others ails a bit. As for the rest, he is a model to imitate. With his works and righteousness, he merits justification. He rightfully deserves paradise.

As for the Publican: his repentance—certainly—places him along a good road. However lowered eyes and a generic sorrow are not sufficient to reconcile with God and people. Something more is needed: that he returns to the poor the stolen money and fulfills the prescriptions of the law because God’s terrible and sudden punishments imposed on him will surely fall.

If we agree with this conclusion of the parable, then we have the right disposition to receive the lesson of Jesus: “I tell you, the Publican returned home justified unlike the other.” We cannot agree with this sentence. How can one condemn a person who has behaved well and declare just the sinner? Our criteria of justice are distorted.

The reversal of the judgment is not about the moral behavior of the two.

Jesus does not say that the Publican is good and the Pharisee bad and a liar. He does not say that one is fundamentally virtuous while the other is a sinner who managed to hide his sins. He only says that the first “was justified,” that is, was made just by God. The second returned home as before, with all his undeniable good works but without saying that God was able to make him just. This is the point.

What is the Pharisee’s error? He makes an error because he puts himself before God in a wrong way. He goes to the temple carrying with him a load of good works accumulated with rigorous penance and through the scrupulous observance of all the commandments. He is convinced that this is sufficient to merit him righteousness. As if he would say to the Lord: look what a marvelous life I’m presenting! To tell you the truth: I astonished you! You did not expect to have such a faithful worshiper, who declares that I am “just”!

Note: the Pharisee does not ask God to be made righteous. From God he only claims that he declares, acknowledges—as does an exemplary notary—the righteousness that he has built with his own hands. He does not understand that all his good works put together do not confer on him the right to salvation. There is no guarantee that whoever does good merits anything; one has only to thank the Lord who guided him/her on the road to happiness. Good works do not make people righteous. They are the signs that the Lord has made us righteous. Good works are like fruits revealing that the tree is full of life. But the fruits do not make the tree alive. Before God, a person finds himself/herself empty handed. He/She has nothing of himself/herself to show. He/She has nothing that makes him/her worthy of divine complacency.

Whoever reasons like the Pharisee is not bad. He/She is only naïve. S/he behaves like the person who thinks of meriting the inheritance of the father because s/he is a model student, not a drug-addict and a no nonsense person. He/She acts in a correct way by doing his/her own good and must thank the father who educated him/her. The inheritance belongs to the father and could be received as a gift, not earned.

The Publican is not a model of a virtuous life. He is a poor man who knows he can offer to God only his “broken and torn down heart.” The Psalm says “the Lord does not despise it” (Ps 51:19). It is the “hungry who is filled with good things while the rich are sent back empty-handed” (Lk 1:53). He does not even run the risk of an illusion that good acts give him the right to lay claim because he has none.

The Pharisee must not renounce his blameless life but the false image of God in his mind: as an accountant who takes note of good and bad works of people; a distributor of prizes and punishments. From this deformed image of God other troubles come, foremost is the need to create a dividing barrier between righteous and sinners. His very name means separated.

Whoever thinks of accumulating merits before God ends inevitably despising others. S/he does not want to have anything to do with the wicked. Whoever feels righteous is convinced of being able to involve God in this separation. S/he would like to enlist God in his/her group, in the righteous’ club. He would like to make of God a Pharisee. God does not fit here. If God has to choose, God would side with the sinners.

The last sentence: “for whoever exalts himself will be humbled and the one who humbles himself will be exalted” (v. 14) seems an invitation to consider ephemeral the triumphs in this world and to cultivate hope that in the future life the positions will be reversed. It is in this context we should read Jesus’ disclaimer directed to those who confide in his/her own merits. It refers to the Pharisee who exalts his own good works and considers them an advantage before God. He, if he does not want to find himself empty handed (humbled), must accept to make himself small, poor among the poor, debtor among debtors. When he will have taken this attitude he will be in the condition to be filled with gifts by the Lord, as it happened to Mary, the poor, humble servant in whom the Omnipotent worked marvels (Lk 1:48-49).

At this point, the introductory verse becomes important (v. 9). It clarifies to whom the parable is directed to.

The listeners are “some who presumed of being righteous and despised the others.” They are not the Pharisees of Jesus’ time, but the Christians of Luke’s community. It is in them that the dangerous Pharisaical mentality is insinuated. The parable is directed to the Christians of all times because the idea of “meriting” before God is profoundly rooted in the person. No one is completely immune to this “leaven” which pollutes and corrupts the life of the community (Mk 8:16).

Fernando Armellini

Italian missionary and biblical scholar

https://sundaycommentaries.wordpress.com