Daniel Comboni

Misjonarze Kombonianie

Obszar instytucjonalny

Inne linki

Newsletter

Monday, May 12, 2014

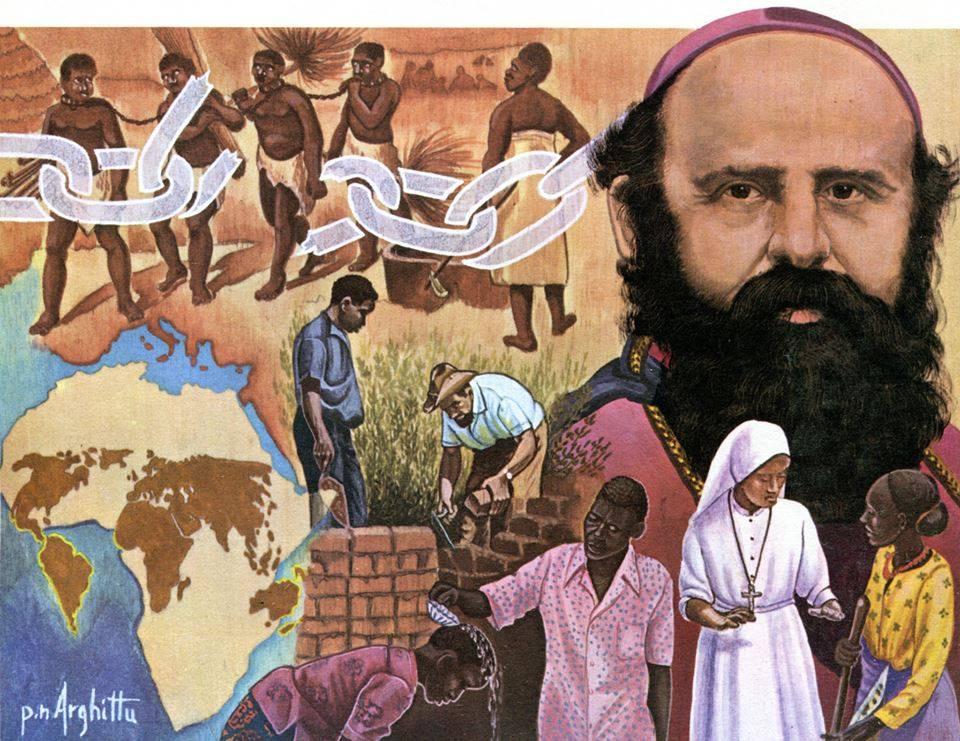

In Limone, from July 10 to July 13, 2009, we celebrated the first Comboni Symposium with the title: “Revisiting the Charism. New Hermeneutical Approaches.” I participated in it with an ambitious paper: “The ‘Hour’ of Africa in the Plan and Postulatum: Yesterday and Today. For a Combonian Systematic Theology of the Kairos.” The symposium underlined the need of adopting a plurality of approaches to Comboni and to his writings… (Fr. Guido Oliana, MCCJ, in the picture).

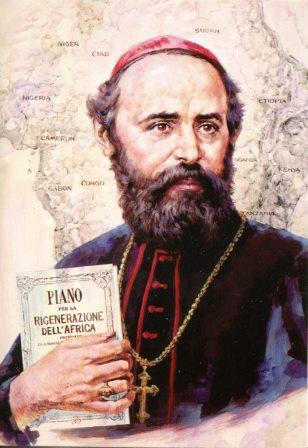

The ‘hour’ of Africa in Comboni’s Plan

Theological considerations

one hundred and fifty years after

(1864-2014)

In Limone, from July 10 to July 13, 2009, we celebrated the first Comboni Symposium with the title: “Revisiting the Charism. New Hermeneutical Approaches.” I participated in it with an ambitious paper: “The ‘Hour’ of Africa in the Plan and Postulatum: Yesterday and Today. For a Combonian Systematic Theology of the Kairos.”[1] The symposium underlined the need of adopting a plurality of approaches to Comboni and to his writings.

In the present contribution, I would like to recall and develop some of those poignant insights in order to show the theological fascination of Comboni’s Plan. The Plan has been studied from both the historical and missiological points of view,[2] but, perhaps, not enough from the theological point of view.

For my purpose, first of all, I need to assume the twofold concept of kairos and chronos that I consider useful categories for a meaningful reading of Comboni’s Plan in the dialectical perspective I would like to utilize. Kairos means a time of great opportunities, a time “pregnant of grace,” that calls for a courageous response. On the contrary, chronos indicates the fatalistic flow of time that gives rise to a rather pessimistic, if not destructive, experience of reality.

According to the New Testament, especially the Gospel of John, the central historical kairos is the Paschal Mystery of Christ, which is a dialectical reality, whereby life and death confront each other in a kind of duel, as the Paschal Sequence of the liturgy states[3], to reach a qualitative transformation of life, properly called glorious, immortal or eternal life. This central kairos expresses itself in what we can name “kairological situations” (kairoi or “signs of the time”) that point to favourable conditions for the interventions of God’s saving grace. In these situations, human liberty and creativity are stimulated toward audacious decisions and actions of daring faith and gratuitous love. These situations open up reality to new opportunities of creative transformation. These moments are in dialectical tension with what we can call “chronological situations” that are negative conditions, which, if left to themselves, lead fatalistically to ruin. These situations are results of the chronos, which, according the ancient mythology, “eats its very own children.”

Comboni lived a singular spiritual and missionary experience, which is recorded in his writings. The interpreters of Comboni’s will find in his texts the vibrations of this vivid experience of the saving kairos (hour) of Africa.[4]

I present my elaboration in three parts. The first part deals with Comboni’s process of discernment of the African situation through various steps: Comboni’s interpretation of the Plan according to the category of kairos-chronos; Comboni’s use of “experience” as a criterion of discerning the “hour” of Africa; Comboni’s scholarly study of geographical, historical and cultural conditions of Africa in view of contextualizing his discernment. The second part deals with the content of kairos, the Paschal Mystery, at work in Africa, highlighting the love of the Trinity for Africa, thus showing: the heart of Jesus beating also for Africa; the “Cross being implanted in the heart of the Triune God”, according to a moving image of Jürgen Moltmann;[5] God’s wound of love for Africa being felt by the missionary himself/herself. The third part envisions the accomplishment of the Plan of the Regeneration of Africa in terms of an integral (human and spiritual) transformation of African people, joyfully celebrated in Baptism.

1. Reading the “hour of Africa”

We need, first, to see how the dialectical category of kairos-chronos becomes an interpretation key of the Plan highlighting the African missionary scenario of Comboni.

a) Chronos and kairos in the Plan

In the Plan, the chronos is expressed by the following threefold “chronological situations”: the natural-geographical, the anthropological-cultural and the ecclesial-missionary situations. Some expressions used by Comboni to describe the conditions of African populations at his time today may sound rather harsh and perhaps offensive. We take them realistically as Comboni wrote them to show the contrast with the perspective of transformation - as Comboni himself envisioned - that the Gospel would bring about.

The negative natural conditions point to the “inhospitable lands”,[6] “burning regions of the Africa interior [...] ruinous for their health” [of the missionaries]),[7] the “fatal African climate [has] brutally cut down even the most physically robust of missionaries”, the “harsh diseases which brought us to the very threshold of the grave” and “the dangerous journeys down the While Nile”.[8]

The negative anthropological-cultural conditions point to the situation of African people at the time of Comboni: “bent low and groaning beneath the yoke of Satan and [...] placed on the threshold of a most terrible precipice”;[9] “brutalized savages”;[10] “unlettered and brutalized peoples [...] living in the most abominable and most degrading fetishism”;[11] still under “the fearful curse of Canaan,”[12] whose passions are “more ferocious than the tropical heat”;[13] “many millions of souls still languishing in the shadow of death”; “vast and populous regions cloaked in unbelief and barbarity”;[14] and, finally, “the fanatical fury of Islam.”[15]

The negative ecclesial-missionary conditions are mainly identified with the context in which “the countless initiatives of those great-hearted heroes came to grief on the rocks of risk and hindrance; their energies were exhausted, they became discouraged and their progress was halted”[16] and “the results achieved were so poor as to amount to nothing”.[17] Many missionaries after some initial attempts “quickly succumbed and soon died, thus rendering fruitless their work for the conversion of the Africans”.[18] These difficult conditions made Propaganda Fide think of the “the hard necessity of abandoning the important mission of Central Africa”.[19]

The kairós is expressed by the progressive “maturation of time” leading to the “fullness of time” for African’s redemption, that is, the possibility of success in the work of evangelization. In linguistic terms, the sense of the novelty of the kairos, which breaks through the fatalistic flow of the chronos, is expressed in the Plan by typical adverbs, which introduce the breakthrough of the kairos, such as “then” or “now.”[20] In other texts of Comboni, we find explicit references to the idea of the kairos, the “hour of Africa,” like “the hour of salvation [...] seems to have sounded”[21] or “the time of the redemption of Africa has come.”[22]

The dimension of the kairos is revealed by the “kairological situations” expressed by natural-geographical, anthropological-cultural and ecclesial-missionary conditions but in a favourable perspective.

The geography now does no more appear threatening as an embodiment of the chronos, but friendly and peaceful. We have one summarizing icon of this situation: the river Nile. The Nile, menacing in the perspective of the “chronological situations” (“the dangerous journeys down the While Nile”[23]), now it does collaborate peacefully: “On the banks of the majestic Nile.”[24] In the letter accompanying the Postulatum, the Nile is beautifully described in its collaborative sacramental ministry. “The Nile has finally revealed its sources so that the peoples who live near it may be purified in its waters by Holy Baptism.”[25] We note the emphatic liberating adverb “finally” underlining the end of a negative era: the era of the chronos.

The positive anthropological-cultural conditions for the success of evangelization can be summarized by the process of the “regeneration of Africa by Africa,”[26] concretely expressed by the proper use of the talents of adequately educated and trained African men as craftsmen,[27] catechists[28] and clergy[29] and African women as educators, teachers, housewives[30] and dedicated religious.[31]

The favourable ecclesial-missionary conditions are now found in the deep motivations of faith and love in the missionaries, moved by divine charity and spirit of generous dedication[32] and in the collaboration of many forces in support of the African mission: civil organizations,[33] ecclesiastical institutions,[34] religious orders,[35] missionary animators,[36] missionary societies and all forces of Catholicism.[37]

The duel between chronos and kairos, between life and death, occurs paradigmatically on the Cross of Christ resolving in the victory of life, which is expressed by the spirit of gratuitous love, animated by “hope against hope” (Rom 4:18), embodied in the numerous missionaries who selflessly gave up their lives for the regeneration of Africa. This is the process of the grain of wheat that gets rotten and dies in the soil of the merciless chronos yielding much fruit in the time of the kairos (cf. Jn 12:24). Such duel between death and life, between chronos and kairos, is manifested in Comboni’s Plan and other writings by the sign of the blood and sweat the missionaries poured out in their fight against the “chronological situations.”[38]

Comboni was “a member of those apostolic expeditions” and “by God's mercy, among the very few to survive.”[39] He thus becomes the interpreter of the kairos, of the new sheaves that arose from the seed of the sacrificial charity of his companions, victims of the chronos, “who laboured in the midst of immense privations in this vast field,”[40] buried in “the tombs provided by the African sands.”[41] Their sacrificial charity conquered the implacable chronos.

In sum, the “chronological conditions” in the Plan are expressed by the dialectical duel between the symbols of darkness and light. The symbol of darkness is highlighted by expressions such as “mysterious darkness” and “oppressive gloom.”[42] The “kairological conditions,” namely, the breakthrough of new possibilities for the evangelization of Africa, are emphasized by the symbol of light shining in the darkness in expressions like “supernatural light”;“pure light of faith”; “divine flame”; [43] “a ray of the true light.”[44].

b) Comboni’s reading the “signs of the time” through his personal experience

The Plan mentions the importance of “experience” in the evaluation of particular facts. God manifests himself historically with his offer of salvation at the opportune time (kairos). He knocks – so to speak - at the door of time and space in order to be let in. When we open up to God’s opportunities of grace through our discernment of reality, we perceive God’s “suffering love” for the distorted situation of humanity, in our case of Africa.

Modern thinkers help us to appreciate the theology of the suffering love of God in the crucified Christ, which Comboni sees in relation to Africa. An author describes modern man’s dislike for a God who is distant and detached from humanity and instead highlights modern man’s sympathy for a God who assumes our sinful flesh, giving himself to us unconditionally, and becoming our travelling companion in our life struggles.[45] Contemporary philosophy has also discussed the question of God in relation to evil and suffering.[46] Theologians highlight that the Cross reveals that “God is love” (1 Jn 4:8.16) and, being God Triune, it is not only one Person that suffers, but all three suffer of love for the suffering humanity. The event of the Cross involves the three divine Persons.[47] In one word, the “apathetic” or indifferent God of Greek philosophy in Christ becomes the passionate or “pathetic” God, who suffers with and for humanity.

The discernment of the “signs of the times” in the Africa of Comboni is an exercise of faith, which implies three important moments: 1) the direct personal experience of the “kairological situations”; 2) the scholarly study of the geography of African lands, the reports of the travellers, the anthropological-cultural conditions of the populations and the history of evangelization, with its failures and achievements, leading to discern the “chronological” from the “kairological”; 3) the strategic plan of missionary action in order to promote efficacious interventions for the transformation of the “chronological situations.” Here I would like to ponder explicitly on the first and second aspect. I deal indirectly with the third studied by other scholars.

The term “experience” appears five times in the Plan in contexts that refer to Comboni’s preoccupation about finding a missionary solution at least of some of the difficulties described above as “chronological situations.”

Through direct personal experience, Comboni realizes that the harshness of the climate is a huge obstacle for the missionaries. Moreover, he realizes that the education of Africans in Europe does not bring the desired results, because, on their return to Africa, they find it difficult to adapt themselves to the conditions they had abandoned when they went to Europe.[48]

Through experience, Propaganda Fide itself confirms “the ineffectiveness and inadvisability of the creation of an indigenous clergy, educated in our countries, yet destined to evangelize Central Africa.”[49] Hence: the decision of Propaganda Fide to abandon the Central African mission. The reasons are the same as indicated in the previous texts: the missionary cannot survive in the very hot climate of Africa and the Africans cannot tolerate the cold climate of Europe. Besides, those who survive when they go back to Africa they cannot re-adapt themselves to the African way of life.[50]

Finally, experience teaches that missionaries do not last for too long in the interior of Africa. Hence Comboni suggests adopting a policy of frequent rotation of the missionary personnel of the interior, so that they may survive their harsh conditions until the African local clergy will be ready to take over the institutions run by the missionaries.[51]

In the Plan we find other meaningful expressions referring to experience as a way to grasp the historical manifestation of the saving love of God. Comboni uses a term related to “journey” (“camminando”) precisely in the most important part of the Plan, when after discerning the “chronological obstacles,” he suggests a possible solution: the regeneration of Africa by Africa itself. Comboni suggests “a way along (“camminando”) which the lofty goal may more probably be reached.”[52]

Comboni seems to have found the way, but it is not a magical solution. It implies a patient “journey” which must be followed step by step. In the process (“while journeying,” “along the way”) one will have to make an adequate empirical evaluation of the various situations in the light of the achievements and failures. It is precisely for the realization of such a goal that Comboni writes his Plan. For its progressive implementation Comboni is ready to do anything. “On this goal every thought of our life will be centred and for it we would be happy to pour out the last drop of our blood.”[53]

c) Comboni, scholar of the geographical, historical and cultural conditions of Africa

The discernment of the “signs of the time” (“kairological situations”) implies always an adequate assessment of reality based also on a serious reflection on difficulties and possibilities of the newly proposed way.

Comboni describes his scholarly commitment in various texts. Two texts are meaningful. “We have carefully studied the nature, customs and social conditions of those distant tribes and we have concluded that [...].”[54] And again: “I am [...] not neglecting to study the population, souls, nature and temperament of the people of my Vicariate, subsequently to choose means to attract them to the Faith.”[55]

The study of the “signs of the time” also through geographical and historical investigations is not merely a question of erudition, but an act of faith in salvation history, which is always fulfilled in spatial-temporal coordinates. Study is, therefore, an exercise of faith. It is never redundant. Scholarly study is somehow an act of contemplation of the mystery of Christ continually becoming flesh and being crucified in our distorted and distorting history to liberate its hidden energies of truth, beauty, love and life.

The discernment of the situation and the consequent plan of action as an answer of faith to the “kairological challenges” are essential factors for the fulfilment of God’s plan of salvation. God does not impose himself either ideologically through abstract principles, or legalistically through moral norms, or sentimentally through emotional effusions or passing enthusiasms, but he offers his saving interventions embodied in concrete events through “kairological situations” in time and space.

2. The Paschal mystery at work in Africa

Now we consider the Plan from the perspective of the content of the kairos in the light of the theme of the “pathetic” God who suffers of love for Africa. It is the theme of the Paschal Mystery, which transforms and regenerates Africa through the work of evangelization. The central historical kairos is Jesus Christ, in whom we find the suffering love of God for human beings and the pain of human beings themselves for their situations of alienation and their longing for liberation. The Cross becomes a supreme sign of the love of the Triune God for Africa, showing the heart of Jesus beating also for Africa, sharing his wound of love with the missionary.

a) “Jesus also beat [...] and also died for the Africans”

Comboni highlights the fact that Christ died and suffered also for Africa. “Jesus also beat [...] and also died for the Africans.”[56] The source for Comboni’s “hope against hope” is the fact that on the Cross Africans have already been freed from their curse. “All our trust is the One who died for the Africans.”[57] “It is nonetheless a great comfort to me constantly to remember that these peoples too, eighteen centuries ago, were freed in the blood of Christ from their father's curse, and to think that by that very same blood Christ made them his own heritage.”[58]

The redemption of Africa has once for all been accomplished on the Cross. The Cross of Christ proclaims God’s unconditional love for Africa. The Church becomes the sacrament of Christ, “the sacrament of encounter between God and man,”[59] “sign and instrument [...] of communion with God and of unity among all men.”[60] The missionary represents the Church as the embodiment of Christ the Good Shepherd and the Good Samaritan which looks for the stranded brothers and sisters wounded and bleeding along the roads of history. God cries in Christ for the suffering and wounded Africa.

In the Act of Consecration of the Vicariate to the Sacred Heart on the 14th September 1873, but also in writings after the inspiration of the Plan of 1864, “the three main symbols of the spirituality of Comboni – the Heart, the Cross, and the black Africa – are in strict connection. The connection among them is the ardent love of the Heart of Jesus for the Africans.”[61] Jesus loved and loves Africa. The work of evangelization is precisely to make this love perceivable and experienceable.

b) The “Cross planted in the heart of the Triune God”

How could God crying for Africa be perceived? How could “the water of the divine tears” become that unique bond that could be established between God and the Africans, “brutalized by history” and living in “mute agony”?[62] With his passionate appeals for Africa, Comboni gave voice to the silent tears of God. How could the silence of God before the African situation be interpreted? As an absence? As an abandonment? As the silent sorrow[63] of a “pathetic” God? Comboni became an interpreter of this silence, making God’s crying for Africa resound in Rome: “Why is it that the African interior alone still lies in darkness and in the shadow of death, without a Pastor, without Apostles, without Church and without Faith?”[64]

Was the history of Africa a “history without God”? Through a deep interpretation of faith, filled with “hope against hope”, Comboni would affirm - in the words of Mario Pomilio - that the “history of the victims is the very history of God” and that the suffering Africa was also one cause of the wounds of the crucified Christ. Comboni would announce that this disarmed God on the Cross does not despair, but in his “solidarity not of force and justice, but of compassion and love” wants to become a source of consolation for all the crucified people of history. The Cross of God expresses the pain of every African.[65]

God is in need of human beings to assure them that he loves them and deeply shares in their destiny. “A supreme being, apathetic and indifferent toward human beings, yes could show an idea, but not the living God of Israel.” [66] For Comboni - we could say - only the God of Israel is concerned about the destiny of his people in Africa, and thus could be the God of Africa. Comboni interpreted in favour of Africa the cry of the psalms and prophets which narrate the suffering participation of God in the destiny of his people. Comboni made his contemporaries feel God’s “passion” for Africa, namely, the passion of a God who feels involved in the misfortunes of his sons and daughters (cf. Ps 91:15) and who, “because of his love and compassion, redeemed them, lifting them and carrying them” (Is 63:9).

The “mysterious darkness,”[67] which was covering Central Africa, could be identified with the darkness that was covering Golgotha hill when Jesus died on the Cross (cf. Mk 15:33). The sense of abandonment by God, the Church and the world, which Africa experienced at the time of Comboni, could be identified with the sense of abandonment Jesus experienced on the Cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mk 15:34). The “oppressive gloom,”[68] symbol of the situation of fatalism, superstition and slavery, which for a long time hid Africa from the Church and the world and prevented her from having a liberating relationship with the loving God was torn in two from top to bottom by Christ on the Cross (cf. Mk 15:38).

The “mysterious darkness” and the “oppressive gloom,” signs of the curse of Canaan, produced by the implacable chronos, which fatalistically afflicted Africa leaving her without hope, are now enlightened by “the pure light of faith”[69] and by the “spirit of the Gospel”[70] through “the spirit of the apostolate.”[71] Such a burst of light is somehow a reflection of the Shehkinah (glory) of God, which descends on Africa to get involved in her destiny and let itself be wounded by her history in order to share anthropomorphically – as it were - in her death and life, thus showing her its love, finally, in the suffering flesh of Jesus Christ.[72] The mercy of God is not, therefore, only “concern, suffering of one who feels pity from outside, but is sharing of the Holy One”[73] who identifies himself with the destiny of the African people. God protests against the ideology of the curse of Canaan, which the racist western ideology claimed God had pronounced on the Africans.

The love of God-bridegroom for the beautiful black bride will be fulfilled in the encounter of love on the Cross of Christ-bridegroom, as the Fathers of the Church put it, from whose side as the new Adam is born the Church-bride as the new Eve.[74] As every authentic experience of love transforms and energizes the person who feels to be gratuitously and fully accepted, so Africa feels to be regenerated and transformed by the living experience of God’s love in Jesus Christ-bridegroom, when she feels gratuitousy and fully accepted in her predicament. Thus Africa becomes integral part of the beauty of the Church his bride, who “conquered for Christ, [is] shining out like a dark pearl in the heavenly bejewelled diadem of the the Victorious and Immaculate Mary Mother of God.”[75]

The experience of a God suffering of love, passionately but silently involved in the history of Africa, is well expressed by the poignant image of the “Cross implanted in the heart of the Triune God,” according to Moltmann. For Comboni, God is not a God who is distant and impassible. Comboni’s pleas for Africa implicitly speak of a God who is passionate about his African people. Comboni would agree with Moltmann that “the doctrine of apathy of the divine nature, finally, should be removed from Christian theodicy, thus allowing us to see the Cross of Golgotha implanted in the heart of the Triune God so that we may perceive the God who reveals himself in the Crucified.”[76]

The image of the “Cross implanted in the heart of the Triune God” is reflected in the ecclesiological vision of Comboni, evoked also in the Plan. “We shall plant the Cross in many places.”[77] And again: “We hope [...] to be able to establish and implant in this torride land od Central Africa the glorious standard of the adored Cross of Jesus Christ.”[78] The purpose of the missionaries’s work was “to raise the standard of the Cross among those unlettered and brutalized people who were living in the most abominable and degrading fetishism.”[79]

The Trinitarian vision that Comboni contemplates through the “pure light of faith” is precisely the “Cross implanted in the heart of the Triune God,” that is, the Heart of Christ, where the Trinity expresses its heartbeats for Africa. From this heart flow the charity and the spirit of the Gospel, which spread throughout the world through the work of evangelization. “Then he [the Catholic] was carried away under the impetus of that love set alight by the divine flame on Calvary hill, when it came forth from the side of the Crucified One to embrace the whole human family; he felt his heart beat faster, and a divine power seemed to drive him towards those unknown lands. There he would enclose in his arms in an embrace of peace and of love those unfortunate brothers of his upon whom it seemed that the fearful curse of Canaan still bore down.”[80]

God the Father suffers for his African children, for the curse inflicted on them by an erroneous ideological interpretation that sees God himself as the one responsible for it. The suffering for this curse touches personally God the Father, who loves all his children without discrimination and make his sun rise over both Europeans and Africans (cf. Mt 5:45). God suffered not ony for his suffering children of Africa, but also for the racist attitude of his other children. With his blood, Jesus Christ redeemed also these brothers and sisters of his, children of the same Father, and acquiring them as his heritage.[81]

The passionate love of God the Father for Africa through the pierced heart of the Son, wounded by love, becomes the strength of the Holy Spirit (“divine power”) that moves the missionary from whithin to stretch out his arms in a gesture of tenderness and love to welcome all African populations as brothers and sisters in a solidary embrace of peace and reconciliation. The vision of the Church in Africa as “family of God,” highlighted by first Synod of Bishops for Africa, is here prophetically anticipated.[82]

c) The wound of love of God and of the missionary for Africa

The love of the Triune God, wounded with compassion for Africa, hurts also those who share in the loving heartbeats of the heart of Christ. Comboni states in the Plan: the Catholic “felt his heart beat faster, and a divine power seemed to drive him towards those unknown lands.”[83] And again: “The heart of every good and faithful Catholic, inflamed as it must be by the spirit of the love of Jesus Christ, will surely be deeply wounded and grievously stricken by the appalling idea of seeing the Church suspend, perhaps for many centuries, her work on behalf of so many millions of souls still languishing in the shadow of death.”[84] In another passage Comboni says: “Yet we shall be forgiven if the impulse of our heart, where we feel most strongly the cry of misery directed towards us all by those unhappy sons of Adam who are our brothers, should carry our mind away from the path of truth and certainty.”[85]

In other words, the missionary feels the thirst of Christ on the Cross: “I thirst” (Jn 19:28). This is not a mere physiological thirst of the dying Jesus, but is a spiritual, moral and apostolic thirst or burning desire for people totally dedicated, like him the Son, to the glory of God the Father and to the welfare of their brothers and sisters.

The bleeding wound of compassion and deep solidarity that the Apostle of Africa feels, thus sharing the wound of love of the Triune God, expressed in the thirst of Jesus, is the perception of the self-manifestation of God in the various situations of suffering Africans. The perception of this kairos invites the missionary Church to take courageous responsible actions in favour of the regeneration of Africa. In this way, Africa is made to experience the eternal love of God the Father, the eternal brotherhood of God the Son and the eternal communion of love with the Father and the Son in the Holy Spirit.

3. The Plan for the Rigeneration of Africa is now being accomplished

God’s eternal covenant of love in the blood of Christ is finally experienced and celebrated by Africa, now “enlightened by a ray of the true light” through the “Holy Church, echo of the Eternal Word of the Son of God across the centuries.” Now Africa feels regenerated by Christ through the Holy Spirit in her vital and creative energies of truth, love, beauty and life thanks to the work of evangelization carried out by Church’s ministers. “Following the example of the Divine Pastor, they will remove the yoke of oppression from their shoulders and bring these wretched creatures into the free and joyful flock of the Church.”[86]

Baptism is the celebration of this achieved liberation and regeneration. The Postulatum expresses the idea of Baptism as source and expression of this new creation, a fecund spousal covenant between Christ the bridegroom and Africa the bride, “dark, but beautiful” (Sng 1:5). Thus the true sources of the Nile are now being discovered. They do not have any more a mere geographical character, but now assume also an ecclesiological symbolism. “Nile has finally revealed its sources so that the peoples who live near it may be purified in its waters by Holy Baptism.”[87]

The chronos, implacably and apathetically indifferent, which expressed itself in adverse conditions (fatal climate, fatalist vision of life, menacing waters of the Nile, deaths of missionaries and inefficiency of the Church) is conquered by the kairos, symbolically expressed by the peaceful and majestic waters of the Nile.[88] The Nile, from being a passive observer, if not collaborator in the situations of misery and slavery of African people, now becomes an interpreter of the regeneration of Africa and a participant minister in its redemption by offering his waters to be sanctified by the Spirit. Africa can experience now the new creation, the final victory of the kairos over the chronos by welcoming and responding to the kairos of the gospel and of the love of the Triune God, creator, redeemer and sanctifier.

The tears of God, who have been lamenting and crying for the “mute agony” of his African people, are finally transformed into tears of joy for his children who have finally entered into his covenant of love. God’s tears of joy are mixed with the tears of repentance and joy of his African children regenerated to new life. These tears of repentance and joy through the baptismal waters join the roaring waters of the Nile that sing and dance happily with its tumultuous and thunderous cataracts and falls celebrating the regeneration of its peoples. The Plan for the Regeneration of Africa is now being accomplished! Comboni’s dream is now being fulfilled!

The victory drum beat and the jubilant dances can now begin to sound freely in the limpid African air!

“Death and Life were locked together in a unique struggle [...]. Death and life have contended in that combat stupendous: [...] Christ indeed from death is risen, our new life obtaining!”[89]

Fr. Guido Oliana

[1] “L’ ‘Ora’ dell’Africa nel Piano e nel Postulatum: ieri e oggi. Per una teologia sistematica comboniana del kairos.” The acts of the symposium appeared partially in the printed booklet but fully in the included CD: “Quaderni di Limone. Rinnovare la missione rivisitando Comboni”, Luglio 20006, Numero 0, Missionari Comboniani, Provincia Italiana, Via del Meloncello 3/3 - 40135 Bologna.

[2] Cf. F. Gonzáles Fernández, Daniele Comboni e la rigenerazione dell’Africa. “Piano”, “Postulatum” “Regole”, Rome: Urbaniana University Press 2003. In the footnotes the book offers an essential bibliography; W. Vidori, Il Piano per la rigenerazione dell’Africa di Daniele Comboni. Storia della genesi, alla luce delle idee ed esperienze che lo hanno preceduto, e nel contesto del movimento missionario del secolo XIX (Roma, Tesi di Licenza all’Università Gregoriana 1985); F. Pierli, Come Eredi, Roma: Missionari Comboniani 1992, 173-199; Aa. Vv., A che serve la missione se ... Relazione del Convegno di Pesaro (Marzo 2004). Comboni: la santità, il piano per la rigenerazione, l’animazione missionaria, Città di Castello, GESP, 2004, in particular the contributions of W. Widori e M.G. Campostrini.

[3] Cf. Paschal Sequence on Easter Sunday: “Mors et vita duello conflixere mirando” (“Death and Life were locked together in a unique struggle”).

[4] Cf. ad ex. Writings, n. 1978; n. 2180; n. 3440; n. 3602. The title Writings refers to the publication: The Writings of St. Daniel Comboni. Correspondence and Reports (1950-1881) of the Founder of the Comboni Missionaries. Preface by Cardinal Caro Maria Martini, London: Comboni Missionaries 2005; trans. from orig. Daniel Comboni, Gli Scritti, Roma: Missionari Comboniani 1991.

[5] J. Moltmann, Il mio itinerario teologico, in Id., Nella storia del Dio trinitario. Contributi per una teologia trinitaria, Brescia: Queriniana 1993, 261, quoted in G. Canobbio, Dio può soffrire?, Brescia: Morcelliana 2005, 15 (my translation).

[6] Writings, n. 2741.

[7] Writings, n. 2743.

[8] Writings, n. 2749.

[9] Writings, n. 2742.

[10] Writings, n. 2749.

[11] Writings, n. 2743; n. 2749.

[12] Writings, n. 2742.

[13] Writings, n. 2745.

[14] Writings, n. 2752.

[15] Writings, n. 2781.

[16] Writings, n. 2741.

[17] Writings, n. 2745.

[18] Writings, n. 2749.

[19] Writings, n. 2751.

[20] The English translation does not not always express these adverbs as instead the original Italian version emphatically does; cf. Writings, n. 2742: “Sennonchè [...] Allora” (“then”); n. 2745: “Sennonchè” (non translated); n. 2757: “Ora [...] tuttavia” (“Now”).

[21] Writings, n. 1978; cf. n. 2180.

[22] Writings, n. 3440; cf. n. 3602.

[23] Writings, n. 2749; cf. n. 6406.

[24] Writings, n. 2744.

[25] Writings, n. 2307.

[26] Writings, n. 2753; n. 2763.

[27] Writings, n. 2773

[28] Writings, n. 2773; n. 2776.

[29] Writings, n. 2776.

[30] Writings, n. 2774.

[31] Writings, n. 2777.

[32] Writings, nn. 2742-2745; n. 2754.

[33] Writings, n. 2741.

[34] Writings, n. 2743; n. 2790; n. 2750; n. 2781 [cf. nn. 2758-2763]; n. 2757.

[35] Writings, n. 2743; n. 2766; n. 2770.

[36] Writings, n. 2744; n. 2749.

[37] Writings, n. 2744; n. 2785; n. 2790.

[39] Writings, n. 2746.

[40] Writings, n. 2744.

[41] Writings, n. 2744.

[42] Writings, n. 2741.

[43] Writings, n. 2742.

[44] Writings, n. 2791.

[45] Cf. ad es. the poignant poem David Maria Turoldo in D.M. Turoldo, Anche Dio è infelice, Casale Monferrato: Piemme 1991, 13: “You did not have tears, but we had to cry. Is this perhaps what moved you to come among us? [...] You had not to be happy and we lost.” Again: “You live on us: You are the truth that does not reason; a God who pains in the heart of man.” (Ibid., 17). God is a “God who looks for human beings; who gets crazy only thinking that some of us got lost; who suffers infinitely more than we do when he thinks of our unhappiness. Thus he is ready for everything, even to loose himself; and does not care at all about what you think of him. God can suffer so that human beings be respected; so that all may live and have bread; all with their dignity and deserved freedom, the freedom even of making mistakes and getting lost, it does not matter: he himself looking for the lost sheep and he will not be peaceful until he has found it” (Ibid., 224-225) (my translation).

[46] Jacques Maritain considers the value of God’s suffering in Christ as source of liberation. “If people knew that God ‘suffers’ with us and much more than us for all the evil that devastates the earth, many things would undoubtedly change, and many souls would be freed. [...] The core of faith implies this certainty that God - Jesus said it in many ways - has for us the feelings of a Father.” J. Maritain, Quelques reflections sur le savoir théologique, in Revue Thomiste 69 (1969) 25-26, quoted in G. Canobbio, Dio può soffrire?, 4 (my translation).

[47] In God we find all possible human suffering, because Jesus’ death “contains all the depth and abyss of human history.” Consequently, “there exists no suffering that in this history of God is not God’s suffering, as there exists no death that has not become God’s death in the history of Golgotha. Id., Il Dio crocifisso. La croce di Cristo fondamento e critica dela teologia cristiana, Brescia, Queriniana 1973, 288, quoted in G. Canobbio, Dio può soffrire?, 59 (my translation). Moltmann hopes that “the doctrine of the apathy of divine nature will eventually be removed from Christian theodicy, thus allowing us to see the Cross of the Golgotha implanted in the heart of the Triune God, so that we may perceive that God reveals himself in the Crucified.” J. Moltmann, Il mio itinerario teologico, in Id., Nella storia del Dio trinitario. Contributi per una teologia trinitaria, Brescia: Queriniana 1993, 261, quoted in G. Canobbio, Dio può soffrire?, 15 (my translation).

[48] Writings, n. 2748.

[49] Writings, n. 2750.

[50] Writings, n. 2751.

[51] Writings, n. 2779.

[52] Cf. Writings, n. 2753.

[53] Writings, n. 2753.

[54] Writings, n. 2746.

[55] Writings, n. 3450.

[56] Writings, n. 5647.

[57] Writings, n. 2459.

[58] Writings, n. 2300.

[59] E. Schillebeeckx, Christ the Sacrament of Encounter with God, London-Melbourn: Sheed and Ward 1963.

[60] Cf. Vatican Council II, Lumen Gentium, n. 1 (ed. A. Flannery).

[61] J.M. Lozano, Vostro per sempre. Daniele Comboni, Bologna: EMI, 2nd ed. 2003, 488 (my translation); cf. Writings, n. 1151.

[62] C. Chalier, Trattato delle lacrime. Fragilità di Dio, fragilità dell’anima, Brescia: Queriniana 2004, 91, quoted in G. Canobbio, Dio può soffrire?, 10 (my translation).

[63] L. Pareyson, Ontologia della libertà. Il male e la sofferenza ,Torino: Enaudi 1995, 221 (my translation).

[64] Writing, n. 2301.

[65] Cf. M. Pomilio, Il Natale del 1833, Milano: Rusconi 1982, 128-129, quoted in F. Castelli, Volti di Gesù nella letteraura moderna, Roma: Edizioni Paoline 1987, 555 (my translation).

[66] A.J. Heschel, Il messaggio dei profeti, Roma: Borla 1981, 24, quoted in G. Canobbio, Dio può soffrire?, 30 (my translation).

[67] Writings, n. 2741.

[68] Writings, n. 2741.

[69] Writings, n. 2741.

[70] Writings, n. 2744; n. 2748.

[71] Writings, n. 2305.

[72] Cf. U. Mauser, Gottesbild und Menschwerdung. Eine Untersuchung zur Einheit des Alten und Neuen Testament, Tübingen: Mohr 1971, 77, quoted in G. Canobbio, Dio può soffrire?, 40.

[73] A. J. Heschel, La discesa della Shekhinah, Magnano, Qiqajon: Comunità di Bose 2003, 28-29, quoted in G. Canobbio, Dio può soffrire?, 35 (my translation).

[74] Cf. Writings, n. 5449.

[75] Writings, n. 2314.

[76] J. Moltmann, Il mio itinerario teologico, 261, quoted in G. Canobbio, Dio può soffrire?, 15 (my translation).

[77] Writings, n. 5055.

[78] Writings, n. 3998.

[79] Writings, n. 2743.

[80] Writings, n. 2742.

[81] Cf. Writings, n. 2300.

[82] Cf. John Paul II, Ecclesia in Africa, Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa 1995, n. 63.

[83] Writings, n. 2742.

[84] Writings, n. 2752.

[85] Writings, n. 2754.

[86] Writings, n. 2791.

[87] Writings, n. 2307.

[88] Cf. Writings, n. 2744.

[89] Paschal Sequence on Easter Sunday.