Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

“Dear poor people, in this world our life is hard and, at times, it seems really like hell: you live in shacks, suffer hunger, cover yourselves with rags, and you are full of wounds. The rich instead live in splendid palaces, squander money in feasts, luxurious villas, and dress themselves in designer clothes. Do not blame yourselves. In the other world, the conditions will be reversed: you will enjoy while they will suffer. It is a question of having a bit of patience and God will change their pleasures into atrocious torments.” (...)

Gospel reflection – Luke 16:19-31

Fernando Armellini

“Dear poor people, in this world our life is hard and, at times, it seems really like hell: you live in shacks, suffer hunger, cover yourselves with rags, and you are full of wounds. The rich instead live in splendid palaces, squander money in feasts, luxurious villas, and dress themselves in designer clothes. Do not blame yourselves. In the other world, the conditions will be reversed: you will enjoy while they will suffer. It is a question of having a bit of patience and God will change their pleasures into atrocious torments.”

Understood so, the parable of the rich Dives and of poor Lazarus becomes “opium of the people.” It serves to placate the poor, nourishing in them the dream of a better future. It will be good also for the rich who, without much anguish for the hell of afterlife, begin to enjoy their paradise in the here and now.

The greatest inequalities were practically inconceivable in ancient Israel where it was not possible to enrich oneself at the expense of the others. At the coming of the jubilee year, in fact, all must be returned to the legitimate owners (Lv 25). But the laws can always be circumvented. Those who are not afraid of the punishment of God had already begun, at the time of the prophets, to add house to house and join field to field (Is 5:8). The small family properties got gradually absorbed by big landowners and the lands ended up in the hands of a very restricted group.

In the time of Jesus, the reversal of this situation was hoped for. The poor people used to say; “One day the powerful will be delivered into the hands of the just ones; they will cut their throats and will kill them without mercy. Those who are counted worthless will dominate over the powerful and the poor will reign over the rich.”

The parable we read in today’s Gospel is born in this context. To understand it we start by identifying the personages.

One who is not named is God who, in the other world, will put in order that which did not go well in this world. His thoughts and his decisions are placed in the mouth of Abraham who in turn, takes the role of protagonist. Then comes the rich man who also recites an important part. The dialogue with Abraham takes two thirds of the story (vv. 24-31). Finally, comes Lazarus, who always remains in the shadow. He does not say even a word; he says absolutely nothing, does not move a finger nor makes a move. He is always seated: on earth by the door of the rich, in heaven at the bosom of Abraham and during the trip is carried by angels.

If we would like to give a title to the parable, it would be wrong to call it: The Parable of the Poor Lazarus (who is not the protagonist), or The Parable of the Evil Rich Man because the main message of the story is about the judgment of God on the distribution of wealth in the world.

In no other parable did Jesus assign names to personages. But here, the poor has a name: Lazarus. In this world, who has a name? To whom are the first pages of the newspapers dedicated to? To the rich, to those who have success! For Jesus, the contrary is true. For him, the rich is any one while the poor has a very expressive name; he is called Lazarus, which means the Lord helps.

After having listed the personages let us focus on each one, starting from the rich man, even though condemned, to say the truth, does not know the reason why. He has not done anything evil: it does not say that he robbed, didn’t pay taxes, ill-treated his servants or blasphemed. He was dissolute, or was not practicing his belief.

Perhaps he is insensible to the needs of others, not helping the poor and so he committed a grave sin of omission. But this does not seem true: Lazarus was at his door and did not go somewhere else. It means that he was getting a few crumbs. The condition in which he was left was inhuman. He had to content himself with the crumbs with which the diners cleaned their fingers (in those times they were not using utensils) and the details about the dogs confer an unmatched realism to the scene.

And the rich man? He lived his life reveling, dressing in the latest fashion, although, always spending of his own. So—according to the current thinking and judging—he had an impeccable moral behavior. Moreover, when Abraham denies him the drop of water, he does not accuse him of any fault. He simply reminds him that he was rich and enjoyed on earth while Lazarus suffered. Then in heaven things are reversed. But it is not explained why. So it is better not to mention the “evil rich man.”

There is a tendency to demonize the rich, to regard them always filled with iniquity and to exalt the poor, putting them up as models of every virtue. Lazarus would be the archetype, the ideal. But were we so confident that Lazarus was perhaps good? What did he do to deserve heaven? Nothing. We noticed him: throughout his life did not lift a finger. One does not say that he was humble and educated, who went to pray in synagogues, who had been a laborious and exemplary family man and that he had become poor because he was struck by misfortune. Who assures us that he was not a slacker, one who had squandered all his possessions? And his wounds, could they not be the result of diseases contracted with a dissolute life? Of him, we only know that on earth he was poor and that his situation was then changed. But it is not explained, why.

What to say then of the attitude of Abraham? None of us—I think—take this character as sympathetic. In Israel, it was believed that he, being the father of the people and the friend of God (Dn 3:35), could, by his intercession, remove his children even from hell. Here he denies a drop of water to a poor man. Can he be at some point heartless? The rich manifests better feelings: though in torments, he cares about his brothers.

Putting all these elements together we can already draw an initial conclusion: the parable is not giving an opinion on the moral behavior of the rich and the poor. It does not mean that whoever behaves well goes to heaven and who does evil goes to hell, because—it is clear—the rich did not commit sins and Lazarus didn’t do good works.

So what? Simple; it means that the parable has another message. Let us delve deeper. In antiquity, stories similar to ours circulated, where the rich always ended badly. A story was told about a rich man who had exploited the poor, and after his death, he was banished into the place of punishment. He was placed under a door and a nail, on which the door revolved, was stuck in his eye so every time someone entered or left, he suffered the torments of hell. The preachers of the time of Jesus often used these colorful images. They willingly spoke of cruel punishments because they were convinced that these threats were needed to make the people come to their senses.

Even Jesus used these images, including those terrible ones: he spoke of banquets, of courses of fresh water, but also of flames that torture, the gnashing of teeth, and an impassable gulf that separates the righteous from the wicked. These are the classic images created by the fertile imagination of the Orientals to represent the afterlife. It would be naive to draw theological conclusions regarding hell, punishment and eternal fire. It would be totally misleading to attribute to God the severe behavior, ruthlessness, almost as cruel as Abraham’s against a repentant sinner.

The big abyss is just a reminder for the disciple of the fundamental truth, that is: the destiny of man is played around in this unique, unrepeatable life.

We come to the message of the parable.

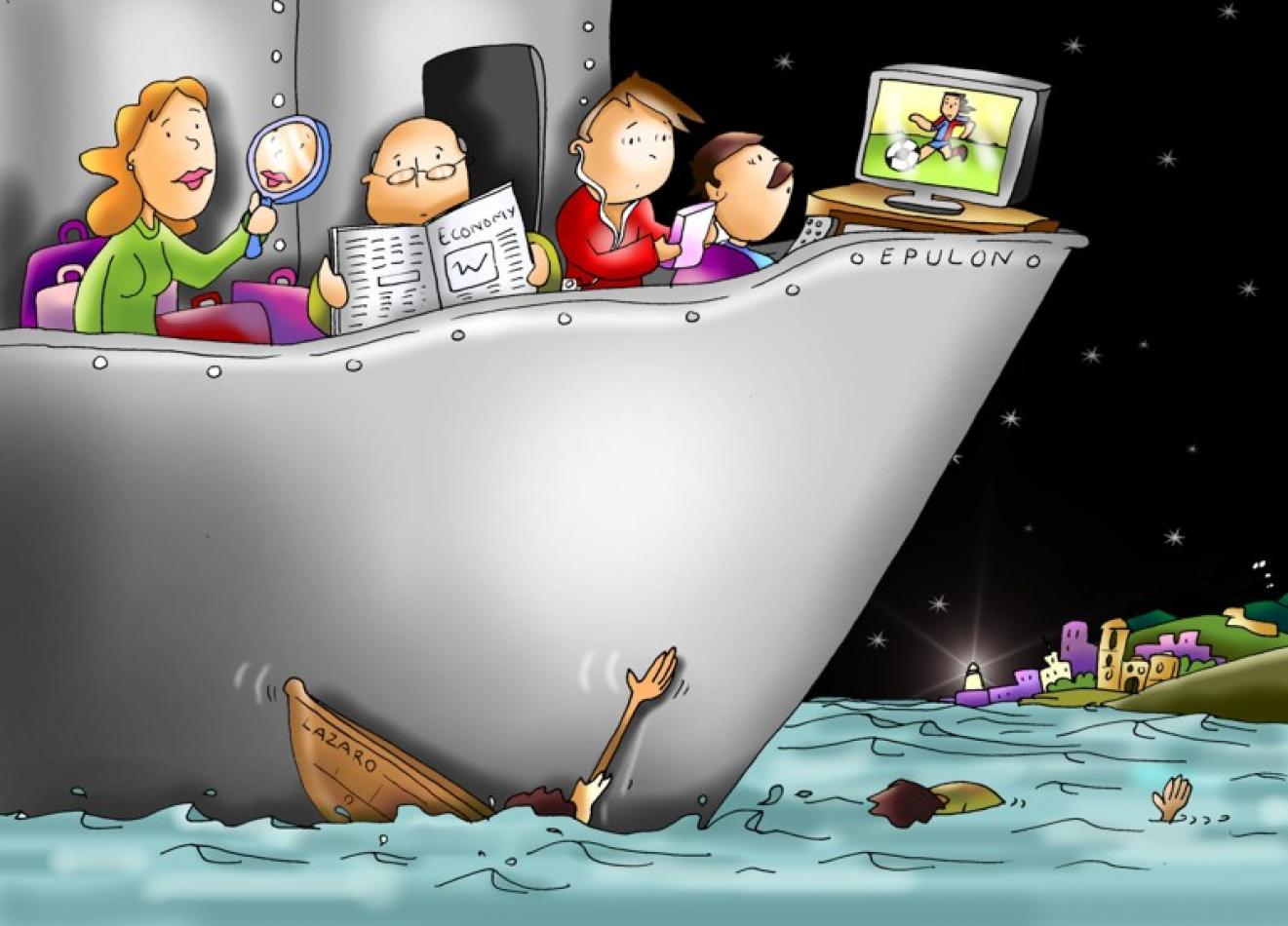

For many, it seems logical and natural to distinguish, between good rich people and evil rich ones. The conviction thus maintained is that inequalities can continue to exist in this world and that the super-rich can live next to the miserable, provided they do not steal and they give alms. Jesus considers this way of thinking dangerous. And this is the conviction that he wants to demolish. In the parable, he speaks of a rich man who was condemned not because he was bad, but simply because he was rich, that is, he locked himself in his world and did not accept the logic of the sharing of goods.

Jesus wants his disciples to understand that the existence in this world of two types of people—the rich and the poor—is against God’s plan. Goods are given to all and those who have more must share with those who have less or having none so that there is equality (cf. 2 Cor 8:13). So, before anyone can enjoy the superfluous, it is necessary that all must have met the most basic needs.

Commenting on this parable, St. Ambrose said: “When you give something to the poor, you don’t offer him what is yours, you give back what is his because the earth and the goods of this world are of all people, not of the rich.”

The last part of the parable (vv. 27-31) shifts the focus on the five brothers of the rich who continue to live in this world. They run the risk of ruining themselves by misusing the assets. They represent the disciples of the Christian communities (number five indicates all the people of Israel) who are tempted to attach the heart to wealth.

How can they be diverted from the seduction it irresistibly exerts? The rich man has his own proposal. He repeats it insistently twice because he thinks it’s the only way of achieving the goal, to cause the conversion, to bring the five brothers to repentance. He pleads father Abraham to convey miraculously—through a vision or a dream—a message from beyond the grave.

Abraham’s response to this trust in the persuasive ability of miracles is firm and clear: the only force capable of detaching the heart of the rich from his goods is God’s Word. “Moses and the prophets” was the formula which, in Jesus’ time, showed all the Sacred Scripture. Only this Word can do the miracle to let the rich man in the realms of heaven. Yes, because it really calls for a miracle, a difficult miracle like letting a camel pass through the eye of a needle (Lk 18:25). Whoever does not let oneself be struck by the Word of God is certainly resistant and insusceptible to any other argument.

Fernando Armellini

Italian missionary and biblical scholar

https://sundaycommentaries.wordpress.com