Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

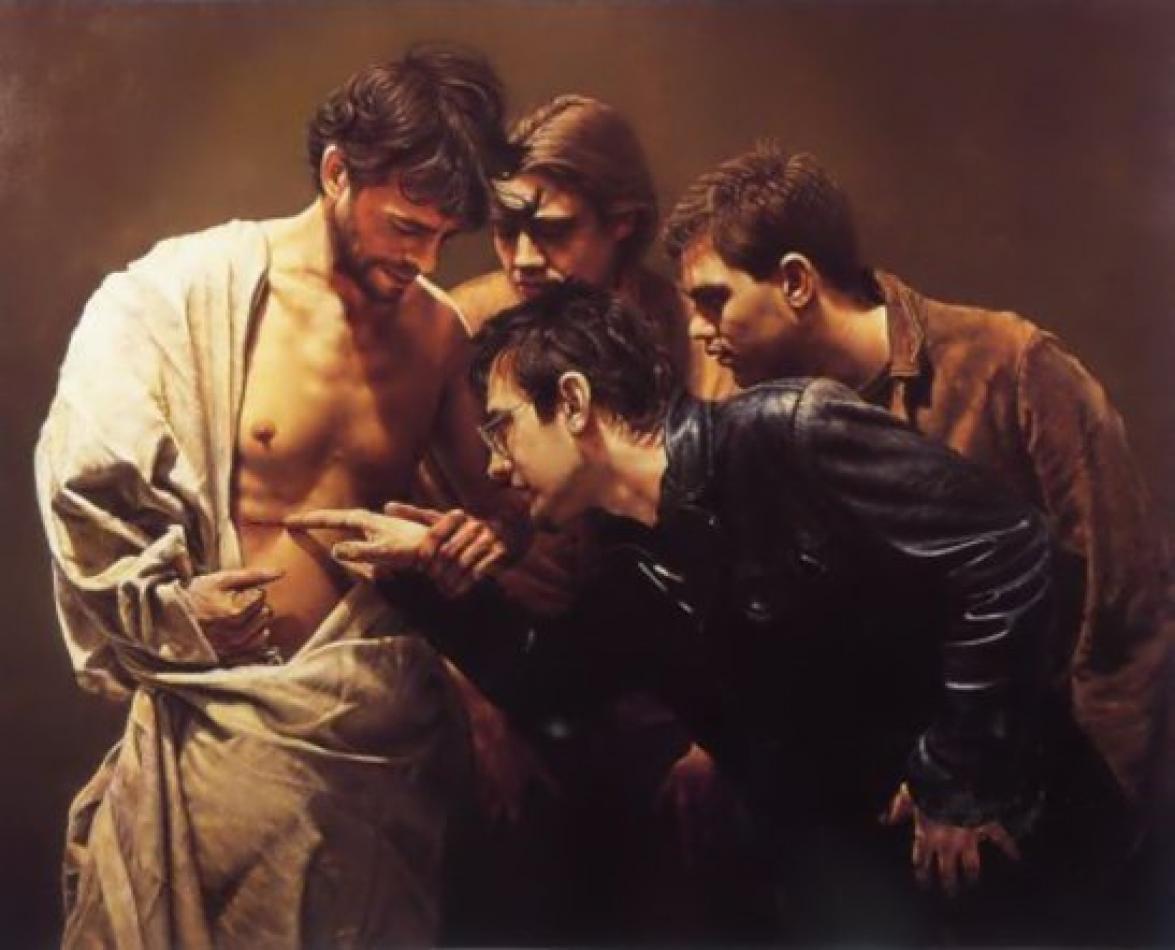

In today’s Gospel, we hear, over and over, the word “see”. The disciples rejoiced when they saw the Lord (Jn 20:20). They tell Thomas: “We have seen the Lord” (v. 25). But the Gospel does not describe how they saw him; it does not describe the risen Jesus. It simply mentions one detail: “He showed them his hands and his side” (v. 20).

John 20: 19-31

Gospel reflection

Pope Francis

In today’s Gospel, we hear, over and over, the word “see”. The disciples rejoiced when they saw the Lord (Jn 20:20). They tell Thomas: “We have seen the Lord” (v. 25). But the Gospel does not describe how they saw him; it does not describe the risen Jesus. It simply mentions one detail: “He showed them his hands and his side” (v. 20). It is as if the Gospel wants to tell us that that is how the disciples recognized Jesus: through his wounds. The same thing happened to Thomas. He too wanted to see “the mark of the nails in his hands” (v. 25), and after seeing, he believed (v. 27).

Despite his lack of faith, we should be grateful to Thomas, because he was not content to hear from others that Jesus was alive, or merely to see him in the flesh. He wanted to see inside, to touch with his hand the Lord’s wounds, the signs of his love. The Gospel calls Thomas Didymus (v. 24), meaning the Twin, and in this he is truly our twin brother. Because for us too, it isn’t enough to know that God exists. A God who is risen but remains distant does not fill our lives; an aloof God does not attract us, however just and holy he may be. No, we too need to “see God”, to touch him with our hands and to know that he is risen, and risen for us.

How can we see him? Like the disciples: through his wounds. Gazing upon those wounds, the disciples understood the depth of his love. They understood that he had forgiven them, even though some had denied him and abandoned him. To enter into Jesus’ wounds is to contemplate the boundless love flowing from his heart. This is the way. It is to realize that his heart beats for me, for you, for each one of us. Dear brothers and sisters, we can consider ourselves Christians, call ourselves Christians and speak about the many beautiful values of faith, but, like the disciples, we need to see Jesus by touching his love. Only thus can we go to the heart of the faith and, like the disciples, find peace and joy (cf. vv. 19-20) beyond all doubt.

Thomas, after seeing the Lord’s wounds, cried out: “My Lord and my God!” (v. 28). I would like to reflect on the adjective that Thomas repeats: my. It is a possessive adjective. When we think about it, it might seem inappropriate to use it of God. How can God be mine? How can I make the Almighty mine? The truth is, by saying my, we do not profane God, but honour his mercy. Because God wished to “become ours”. As in a love story, we tell him: “You became man for me, you died and rose for me and thus you are not only God; you are my God, you are my life. In you I have found the love that I was looking for, and much more than I could ever have imagined”.

God takes no offence at being “ours”, because love demands confidence, mercy demands trust. At the very beginning of the Ten Commandments, God said: “I am the Lord your God” (Ex 20:2), and reaffirmed: “I, the Lord your God am a jealous God” (v. 5). Here we see how God presents himself as a jealous lover who calls himself your God. From the depths of Thomas’s heart comes the reply: “My Lord and my God!” As today we enter, through Christ’s wounds, into the mystery of God, we come to realize that mercy is not simply one of his qualities among others, but the very beating of his heart. Then, like Thomas, we no longer live as disciples, uncertain, devout but wavering. We too fall in love with the Lord! We must not be afraid of these words: to fall in lovewith the Lord.

How can we savour this love? How can we touch today with our hand the mercy of Jesus? Again, the Gospel offers a clue, when it stresses that the very evening of Easter (cf. v. 19), soon after rising from the dead, Jesus begins by granting the Spirit for the forgiveness of sins. To experience love, we need to begin there: to let ourselves be forgiven. To let ourselves be forgiven. I ask myself, and each one of you: do I allow myself to be forgiven? To experience that love, we need to begin there. Do I allow myself to be forgiven? “But, Father, going to confession may seem difficult…”. Before God we are tempted to do what the disciples did in the Gospel: to barricade ourselves behind closed doors. They did it out of fear, yet we too can be afraid, ashamed to open our hearts and confess our sins. May the Lord grant us the grace to understand shame, to see it not as a closed door, but as the first step towards an encounter. When we feel ashamed, we should be grateful: this means that we do not accept evil, and that is good. Shame is a secret invitation of the soul that needs the Lord to overcome evil. The tragedy is when we are no longer ashamed of anything. Let us not be afraid to experience shame! Let us pass from shame to forgiveness! Do not be afraid to be ashamed! Do not be afraid.

But there is still one door that remains closed before the Lord’s forgiveness, the door of resignation. Resignation is always a closed door. The disciples experienced it at Easter, when they recognized with disappointment how everything appeared to go back to what it had been before. They were still in Jerusalem, disheartened; the “Jesus chapter” of their lives seemed finished, and after having spent so much time with him, nothing had changed, they were resigned. We too might think: “I’ve been a Christian for all this time, but nothing has changed in me; I keep committing the same sins”. Then, in discouragement, we give up on mercy. But the Lord challenges us: “Don’t you believe that my mercy is greater than your misery? Are you a backslider? Then be a backslider in asking for mercy, and we will see who comes out on top”.

In any event, – and anyone who is familiar with the sacrament of Reconciliation knows this – it isn’t true that everything remains the way it was. Every time we are forgiven, we are reassured and encouraged, because each time we experience more love, and more embraced by the Father. And when we fall again, precisely because we are loved, we experience even greater sorrow – a beneficial sorrow that slowly detaches us from sin. Then we discover that the power of life is to receive God’s forgiveness and to go forward from forgiveness to forgiveness. This is how life goes: from shame to shame, from forgiveness to forgiveness. This is the Christian life.

After the shame and resignation, there is another closed door. Sometimes it is even ironclad: our sin, the same sin. When I commit a grave sin, if I, in all honesty, do not want to forgive myself, why should God forgive me? This door, however, is only closed on one side, our own; but for God, no door is ever completely closed. As the Gospel tells us, he loves to enter precisely, as we heard, “through closed doors”, when every entrance seems barred. There God works his wonders. He never chooses to abandon us; we are the ones who keep him out. But when we make our confession, something unheard-of happens: we discover that the very sin that kept us apart from the Lord becomes the place where we encounter him. There the God who is wounded by love comes to meet our wounds. He makes our wretched wounds like his own glorious wounds. There is a transformation: my wretched wounds resemble his glorious wounds. Because he is mercy and works wonders in our wretchedness. Let us today, like Thomas, implore the grace to acknowledge our God: to find in his forgiveness our joy, and to find in his mercy our hope.