Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

Saturday, April 16, 2022

Peace and blessings to you and your loved ones for the approaching Easter. After a few months in the Congo, what can I tell you? I was expecting everything but what happened during the weeks overlapping January-February 2022 was a true experience of death and resurrection in events and memories. A journey to Easter.

In events, it was the story of Ivan Cremonesi, the brother of our community. Suddenly his health, already not excellent, began to decline: he isolated himself three days in his room; then analysis and transfusions, in and out of the hospital. Later on, he appeared to have difficulty with concentration, the inability to stand up & with the suspicion of double thrombosis of the femoral arteries. Doctors ordered an immediate return to Italy. Butembo has only flights out to Goma with small planes. It was a set of problems and suffering for Ivan, big by nature and swollen by kidney failure. This kidney problem came up in Goma’s hospital with the pulmonary embolism suspicion and an abdominal occlusion in progress: a medical situation even more complicated by a completely out of order arterial pressure. In Goma, therefore, there were two days of trouble: the trip to Italy was suspended; the search for emergency medicines came in with the decisions of immediate surgical interventions suddenly opposed by the changing clinical situation. On the evening of February 7th, a sudden, illusory improvement predisposed an attempt to resolve kidney failure preventing any other intervention. Then, at dawn on the 8th, the sudden death.

Confusing days followed. In Goma, we have no Comboni community. It was decided to transfer the brother’s body to Kinshasa. However, there were problems of documents, of the right coffin according to the rules in such a case, of the flight-cargo, the long and uncertain hours of waiting between one-step and another. Finally, the flight: I was sitting between the cabin pilot and the cargo area. In Kinshasa at mid-night, the body transfer to the morgue, then the funeral and the return via Kinshasa-Goma, Goma-Butembo with all the inconveniences, never easy in this country although this time kept in the normal boundaries.

I had been in Goma once in 1971 as a tourist from Burundi and passing through towards Butembo a few months earlier. I knew neither the city nor any person. Yet everything worked out quite easily: Gianni, the representative of the Italian embassy, who did not even know the Comboni Missionaries, spent a lot of time solving the ambulance problems at our arrival in Goma, finding the place in the hospital and the urgent care, even advancing some expenses. The owner of Buzy Bee, the airline that flies Butembo-Goma, whose wife several years ago received a support from a Comboni Father, got us the seat from Butembo and organized the Goma-Kinshasa cargo flight. At the hospital, hitherto unknown doctors, nurses and religious offered us unconditional welcome, sympathy and assistance. Finally, my decision to continue, at least for a while, with Ivan's commitment in the carpentry school for difficult boys brought to these first weeks of 2022 a beam of light: from sadness and death tasting events a warmth of Easter resurrecting life always comes.

Meanwhile, as someone already knows and of what I inform everyone here, we started a Flickr, an online photo archive, open to everyone, in which I recall my mission life. Starting with the first mission, Burundi, the Miduha photos reappeared with its unforgettable event.

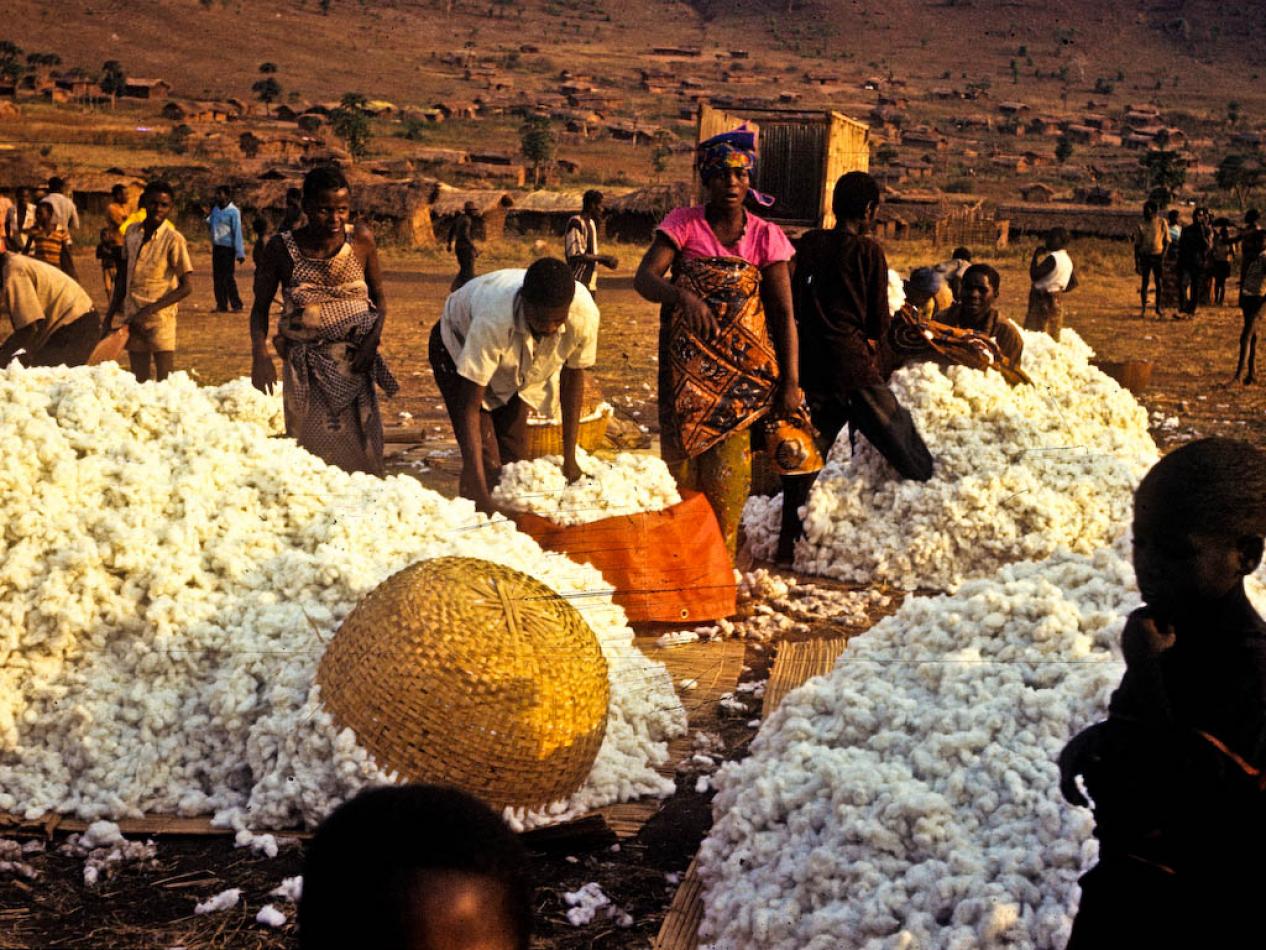

Miduha was an area of Cibitoke Parish where hundreds of "immigrants" were "massed". Actually, they were Barundi. They had emigrated to the Congo to work in the Katanga mines - some named them King Solomon's gold mines - and had returned to escape the Simba Revolution which in the 1964-65 years bloodied the Congo and brought Mobutu to power. After crossing the border, they hastily settled on an "empty" esplanade, only to discover that it belonged to a Belgian cotton company. The company pretended to give them a welcoming attitude: they didn’t need to pay "any rent", they were to receive in advance food, seeds and tools to cultivate, on the sole condition of growing cotton, only cotton, which would make them able to repay the loans.

It was 1972. I had just arrived in Cibitoke. I went to visit them with a catechist. Starting from Rukana, one of our chapel, one entered an esplanade of black earth, typical of cotton fields, which apparently, under the burning sun of that day, stretched out towards the horizon because it ended on barren hills of black rocks. The welcome was rather cold if not hostile: after all, I was a muzungu, a white man like the owners of the cotton company.

To make friends, the following summer, I suppose it was 1973, I took there an “Africa 70” group of young people. The unexpected happened that I find documented in my faded photos.

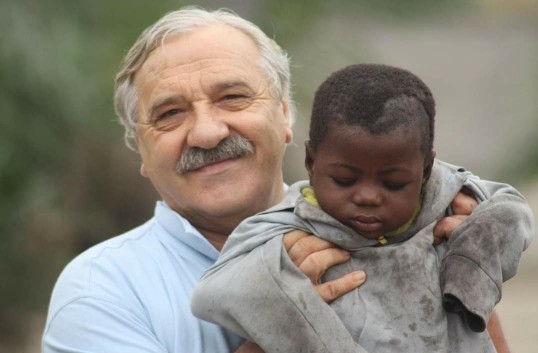

A mother comes towards me, asking for baptism for her baby because it is sick. I do not pay much attention, she has to come and see me the following Sunday at the Rukana chapel. A young girl of the group, intrigued, takes the little one in her arms and, frightened, screams at me: Baptize him, can’t you see that he is dying ... of hunger. Shocked, I improvise the ceremony and then question the small group of those present about what happened. They speak out. They have lived there almost like slaves for years: making loans, growing cotton, selling it to the company, starting over with loans. Without school, without medical center, without a nearby market, without food-producing crops: only cotton, debts, loans, and the meager food bought from the company or a distant market.

I made up my mind. I went to see Mgr. Ntuyahaga, our bishop. I was so convincing, I think, that he went with me to see the cotton company’s director. As a good Tutsi, he did not need to raise his voice to make it clear that either the cotton company accepted our proposal or we would introduce a complaint. The authorization was given to Miduha’s people to cultivate food-producing fields along the stream running down the black hills of the cotton fields.

When I visited them a few months later in the Land Rover, I had then access to Miduha through the company's road, it was a splendid sunny afternoon refreshed by the seasonal rains. They welcomed me joyfully; they made me visit the whole area before the community dinner they had prepared. They showed my night-hut and told me to keep the Land Rover in the cotton shed, "we don't want someone stealing pieces from it."

The next day adults were all in the cotton fields but a swarm of little ones dragged me running towards the small river to show me their "wonders". Banana plants of various types, fresh vegetables, beans, some orange and lemon plants. A beauty. I had a doubt. "You made me put the Land Rover under the cotton shed to avoid thefts, and here, far from your houses, how do you avoid thefts?" With the serious tone of a house’s mother, a little girl about 8 years old told me: "But here stealing is forbidden!"

The rhythm of life and death brings life back for those who believe: it can also give hope while facing in dismay the ongoing war. Perhaps, we also need the wisdom of that child: accepting the weaknesses and selfishness of which humanity is imbued, we should wisely clarify a difference, and say “for this, patience”, “but for that, absolutely not” because coexistence would become impossible.

Happy Resurrection Easter

Fr. Gian Paolo Pezzi