Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

Friday, May 21, 2021

The model of Christian Mission as Service, inspired by the Second Vatican Council, suggests a deepening of the reflection on ministries in the Church and social transformation - and offers the context in which to place the current debate on ministries in the Comboni Institute. [Fr. Manuel Augusto Lopes Ferreira, mccj]

1. Introduction

At first it seemed spontaneous to me to add, as a subtitle to this text, Ministeriality in the Comboni Institute, that is, to add a word now in use that would explain the reason for this reflection: the desire to make a contribution to the ongoing "debate" among us on ministries and, in particular, on so-called "social" ministries.

But, immediately, the word seemed inadequate, too theoretical, ideological. Since it began to appear in our texts, I have been curious: what do we mean by the word ministeriality? What "fifth essence" do we want to talk about, with this substantiation of the adjective ministerial? What quality do we want to affirm? In my original language, the word does not exist. I have looked in Italian dictionaries and have not found it. The dictionaries mention the word ministry, which they define as "an office of great moral and social responsibility, carried out with a sense of duty in favour of the community; mission" [1].

Then, I realised that perhaps I was looking for the word in the wrong place. And I went to look in the various dictionaries of Theology, Biblical and Pastoral dictionaries, Spirituality and Missiology [2]. Here too I found the word ministry, ministries, elaborations on ordained and non-ordained ministries in the Church, in-depth studies on pastoral ministries [3], on lay ministries [4], but no ministeriality.

Lastly, I looked on the internet, where I should have started... I googled ministeriality, but nothing came up; then ministeriality in the Church and something came up, including texts circulated on our sites and prepared by Comboni missionaries, as well as a text from Civiltà Cattolica. Then I searched on the authoritative (?) Wikipedia, but ministeriality did not come up; as a response, I got an invitation to prepare a page on the subject. A few days ago, I had read that the Accademia dei Lincei had validated some words, neologisms coined by Pope Francis, but even here I could not find the recognition of the word ministeriality. So, I decided on the subtitle at the beginning, "Ministries in the Comboni Institute", opening it to the Church and society and trying to integrate the historical perspective.

2. What are we talking about?

It is important to clarify what we are talking about when we say ministeriality, in order to try to speak concretely and not just to use more or less current fashionable words. Let us therefore borrow a definition, which we prefer for its clarity [5]. "The term is a neologism. In simple terms, it means a spirit of competent service at different levels and in different tasks. (...). The meaning of the term ministeriality is based on the etymological meaning of the Latin word 'minister' (minister), which recalls the word 'manus' (hand). The minister was the servant at the table, representing the lord of the house who had called and organised a feast. Since the lord of the house could not personally serve the many diners, the 'ministers' or table servants represented him. They were the extension of his hands, that is, the extension of his generosity, hospitality and family spirit".

As we speak of ministries in the Church and in the Comboni Institute, we need to refer to Jesus and his movement. "Jesus taught his apostles to consider their function as a service (Mk 10, 42 ff)"[6]. And in the early Church the word ministry is used for other services, beyond the apostolate of the twelve: "The term diakonia is applied above all to material services necessary for the community, such as the service of the tables (Acts 6, 1 and 4; 12, 29; Rom 15, 31)"[7].

Any brief search for ministries in biblical theology dictionaries shows us the path that reflection on ministries has taken in the Church: from theological and ontological consideration to a more pastoral and missionary consideration; from the prevalence of ordained ministries to the consideration of non-ordained ministries; from the Christological foundation of ministries to the charismatic origin of ministries in the action of the Holy Spirit; from theological consideration to the ecclesiological development of ministries. Every Christian, therefore, by virtue of Baptism, receives a call to exercise ministries in three spheres: prophetic, regal and priestly, in the image of Christ[8].

Here we can only hint at this path, focusing our attention on the goal set by the Second Vatican Council. For us, the Council's reflection remains the point of reference for a correct understanding of the ministries in the Church today. It offers us the fundamental references to which we go when we speak of ministries: their unity, diversity and complementarity. Vatican II “teaches that the office entrusted by Christ to the shepherds of his people is a true service (LG 24)" and that "the church itself, by its very nature, is diakonia, service (LG 8 and GS 21")[9].

The Catechism of the Catholic Church emphasises, in conclusion, that "Christ himself is the origin of ministry in the Church" (nº 874), that ministries "tend to the good of the whole body" and that "all are called to carry out (ministries) according to the condition of each one" (nº 871); the differences of ministries in the Church "are a function of its unity and mission" (nº 873).

3. Our perspective: synthesis and integration

Our perspective is, therefore, one that briefly highlights, firstly, the ecclesial matrix of the ministries; and, secondly, their integration. The ministries we are talking about were born in the Church with a twofold origin that refers to each other: Christ and the Holy Spirit, his paschal gift. And they are granted, to each and every one, for a twofold purpose: the internal growth and cohesion of the Church, on the one hand, and the witness, that is, the external growth of the Church (see, for example, the first letter to the Corinthians, chapters 12 and 14), on the other.

This perspective, which comes from the New Testament Scriptures, is also taken up by the vision of the Second Vatican Council, which distinguishes and at the same time integrates 'the common priesthood of the faithful and the ministerial or hierarchical priesthood': “although they differ essentially and not only in degree, they are nevertheless ordered to each other, since both, each in its own way, participate in the one priesthood of Christ. The ministerial priest, by the sacred power with which he is invested, forms and governs the priestly people, he performs the Eucharistic sacrifice in the role of Christ and offers it to God in the name of the whole people; the faithful, by virtue of their royal priesthood, share in the offering of the Eucharist, and exercise their priesthood by receiving the sacraments, by prayer and thanksgiving, by the witness of a holy life, by self-denial and active charity”[10]

Vatican II also affirms that there are other ministries besides those ordained and transmitted by the laying on of hands: "Moreover, the Holy Spirit does not limit himself to sanctifying and guiding the people of God by means of the sacraments and ministries, and to adorning them with virtues, but 'distributing to each his gifts as he pleases' (1 Cor 12:11). (1 Cor 12:11), he also dispenses special graces among the faithful of every order, by which he makes them fit and ready to assume various tasks and offices useful for the renewal and greater expansion of the Church according to those words: "To each the manifestation of the Spirit is given that it may be to the common advantage" (1 Cor 12:7). And these charisms, from the most extraordinary to the simplest and most widely diffused, since they are especially suited to the needs of the Church and intended to respond to them, are to be received with gratitude and consolation"[11].

Vatican II recognises the autonomy of science, technology and the secular character of society[12] and affirms that "the laity have a proper, though not exclusive responsibility for temporal tasks and activities. When, therefore, they act as citizens of the world, either individually or in association, they will not only respect the laws proper to each discipline but will strive to acquire true expertise in those fields. They will willingly give their cooperation to those who aim at identical goals. With respect for the demands of faith and filled with its power, they should ceaselessly devise new initiatives where necessary and ensure their implementation"[13].

The Council sees the lay faithful as part of secular society, since "the secular character is proper and peculiar to the laity"[14] and recovers the image that the Letter to Diognetus uses to speak and present Christians in the world: "what the soul is in the body, let Christians be in the world"[15]. Lay Christians "are called by God to contribute, almost from within, in the manner of leaven, to the sanctification of the world by exercising their profession under the guidance of the evangelical spirit, and in this way to manifest Christ to others principally by the witness of their own lives and by the radiance of their faith, hope and charity"; while consecrated (lay) people "by their state bear splendid and exalted witness that the world cannot be transfigured and offered to God without the spirit of the beatitudes"[16].

It is interesting to note that in these two documents cited so far, which are an expression of the self-awareness of the Church of Vatican II (Lumen Gentium) and of its mission in today's world (Gaudium et Spes), the Council does not use the terms ministry to speak about the being and acting of lay Christians in society. It uses, as we have seen, the terms of activity, commitment, profession, competence, cooperation, and the lay faithful are seen, like the whole Church, as being at the service of the integral man[17].

We know that these two documents are not the only words that Vatican II has said about the laity. We also have the conciliar decree Apostolicam Actuositatem on the apostolate of the laity. This document recovers the term ministry/ministries to speak of the lay apostolate. For the exercise of this apostolate "the Holy Spirit also bestows on the faithful particular gifts" (1 Cor 12:7) "distributing them to each one as he wills" (1 Cor 12:11), so that, putting "each one at the service of the others with his gift for the purpose for which he received it, they too may contribute as good dispensers of the various graces received from God" (1 Pt 4:10) to the building up of the whole body in charity (cf. Eph 4:16)[18]. For Vatican II "there is in the Church a diversity of ministry, but a unity of mission"[19].

The lay apostolate is seen as a witness to be given to Jesus Christ and to the Kingdom of God, in the Church and in the world: "The apostolate is exercised in faith, hope and love, virtues which the Holy Spirit pours into the hearts of all the members of the Church (...). (...) All Christians, therefore, are charged with the noble task of working so that the divine message of salvation may be known and accepted by all men throughout the world"[20].

Vatican II affirms that "the laity, therefore, in carrying out this mission, exercise their apostolate in the Church and in the world, in the spiritual and temporal order"[21]; and in the document it offers indications on the aims, the fields and the modalities of the apostolate of the laity, both individual and associative; and it concludes with indications for the formation for the apostolate and the necessary integration of the charisms of the laity with the other charisms in the Church.

We cannot dwell too long here on this conciliar presentation on the laity, but we note that it signals a new path of awareness and action of the laity in the life and mission of the Church. As far as we are concerned, as Comboni missionaries, the Council's vision was at the origin of the relaunching of centres for the formation of the laity (catechetical centres and others...), and the promotion of ministries in Christian communities (the missionary vision that came out of the General Chapter of 1969). The post-conciliar impetus has held together the double perspective - of Lumen Gentium and Gaudium et Spes, on the one hand, and of Apostolicam Actuositatem, on the other - that is, immersion in the secular and autonomous world, as a leaven, leveraging on profession and competence, and apostolate for the witness to Christ, leveraging on the charisms and gifts of the Spirit for the mission of the Church.

4. Social Transformation

Social ministries are closely related to social transformation: we must, therefore, add a reference to social transformation in Vatican II. We take it from the document on the missionary activity of the Church, a word of the council intended especially for us missionaries: "The faithful must commit themselves to the just settlement of economic and social questions... Let Christians contribute to the efforts of those peoples... who are striving to create better conditions of life. In these activities the faithful should strive to collaborate intelligently with the initiatives promoted by private and public institutions, governments, international organizations, the various Christian communities and non-Christian religions. The Church does not wish to interfere in the management of earthly society. She claims for herself no other sphere of competence than that of serving men"[22].

In the subsequent development of the Council, with lay Christians as its subject, the question of their involvement in social transformation took on momentum, that is, the relationship between the Church's mission and society, culture, politics, economics and nature. In Latin America, Liberation Theology and the promotion of Ecclesial Base Communities (CEBs) pressed for a new vision and synthesis between the mission of the Church and society, with the involvement of Christians in the liberation of peoples. In Africa, the liberation movements leveraged the cultural and political identity of the people and the missionaries rethought the relationship between evangelisation and society and promoted the role of the laity in the Church and society. The post-Council ecclesial magisterium (Pope Paul VI with the encyclical Populorum Progressio of 26 March 1967 and the Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi of 8 December 1975) accompanies this reflection and evolution of ecclesial practice.

The dominant perspective is that of preparing the laity for involvement in social transformation, in the political and social spheres, according to the vision of Lumen Gentium and Gaudium et Spes; and for their involvement in the life of the Church, according to the line of ministries and the indications of the decree Apostolicam Actuositatem. In this document, the Council Fathers refer to Catholic Action[23], which has remained paradigmatic of this involvement of the laity in social transformation and of the spirituality for living the Christian faith in the context of secular society. However, in addition to Catholic Action, other movements have pushed lay Christians along this path and enriched the life of the Church, in the immediate post-Conciliar period, with a season rich in fruitfulness and apostolic initiatives, with the appearance of strong Christian personalities in the sphere of politics, economics, and social and cultural transformation (particularly in Europe, with the generation of the fathers who inspired the European Community and the vision of a social Christianity inspired by Vatican II; but also in Africa we have examples, such as the President of Tanzania Julius Nyerere)[24].

5. The interest in ministries

As far as ordained ministries are concerned, the Second Vatican Council deepened and clarified the mission of bishops in the Church[25] and gave indications on the formation, ministry and life of priests[26], omitting an in-depth reflection on presbyters and the current model of the priesthood. In this area of ordained ministries, the only development in the immediate post-conciliar period was the question of the possible ordination of probi viri (proven men), with consideration given to the possibility of ordaining married men. This was an attempt to respond to the lack of ordained ministers in some regions, rather than a sign of the crisis that subsequently opened up in the area of ordained ministries, particularly the priesthood.

The interest in ministries, especially ordained ministries, on the part of the laity, of men and women, married and unmarried, in the Church, is a later development, closer to our own day. This interest can be seen, and evaluated, from various points of view: from an ecclesiological point of view, as a consequence of a reflection that calls for the revision of the models of ministries, ordained and non-ordained, to respond to the needs for growth and cohesion of the Church; from a sociological point of view, as a consequence of the adoption, in the life of the Church, of criteria and values of today's society (such as gender equality, equality between men and women, and rights in democratic society).

This interest of Christian laymen and women in ordained ministries that is emerging in our time, in sometimes surprising forms (such as that of the group of six French Catholic women who offered themselves to the apostolic nuncio in Paris as candidates for episcopal ministry in a vacant diocese), can also be considered from the point of view of the historical development in the post-Vatican Council II period[27] and the evolution of secular society. This interest of lay Christians, both men and women, married and unmarried, in ecclesial ministries, particularly ordained ones, can be seen as a symptom of the laity's retreat into the ecclesial sphere and the withdrawal from the secular society.

This withdrawal has enabled the Church to deal with the crisis of the lack of ordained ministers, particularly priests, by opening up to the laity certain ministries hitherto in the hands of priests. But it has had a negative impact and has revealed a situation that is far removed from the Council's dream: lay Catholics have deserted secular society, renouncing the challenge to spread the Gospel of Christ in it, like yeast.

One can disagree with this interpretation, but one should not ignore the current Church situation: today we are without lay Christians, engaged as such in politics, culture and economics, in the areas in which today's post-modern society is conceived and managed (in Europe, but also in Africa and other continents...). Rather than living as leaven in secular society, and thus evangelising society, as Vatican II had dreamed, the laity now find themselves, in a fall-back movement, secularising the Church; that is, transforming the Church according to the values and parameters of secular society[28].

No matter what one thinks about this question of the ministries and mission of the laity in the Church, one thing is clear today: the role of the laity in social transformation, to put it in the words of the past, or the question of social ministries, to put it in the neologisms of today, is open to discussion, with the Church on the high seas in both areas, ministries and presence in today's society[29]. In this context, the pontificate of Pope Francis appears as a propositional surprise, with his call to the Church of today to reconnect with the dream of the Second Vatican Council, assuming its condition of "outgoing Church" and "field hospital"[30] and repositioning ourselves in the new frontiers (existential, ethical, cultural and social, as well as geographical) in fidelity to the Gospel of Christ[31]. That is to say, with its proposal of an ecclesiology of communion and ministeriality, which sees the Church as a community of disciples-missionaries, going out to serve the world, with the testimony and offering of the Gospel, and which bets a lot on the laity[32].

6. Ministries in the Comboni Institute

In a necessarily brief way, with what has been said so far, we have tried to outline the background against which to place the question of social transformation and ministries in the Comboni Institute, integrating them with a historical perspective.

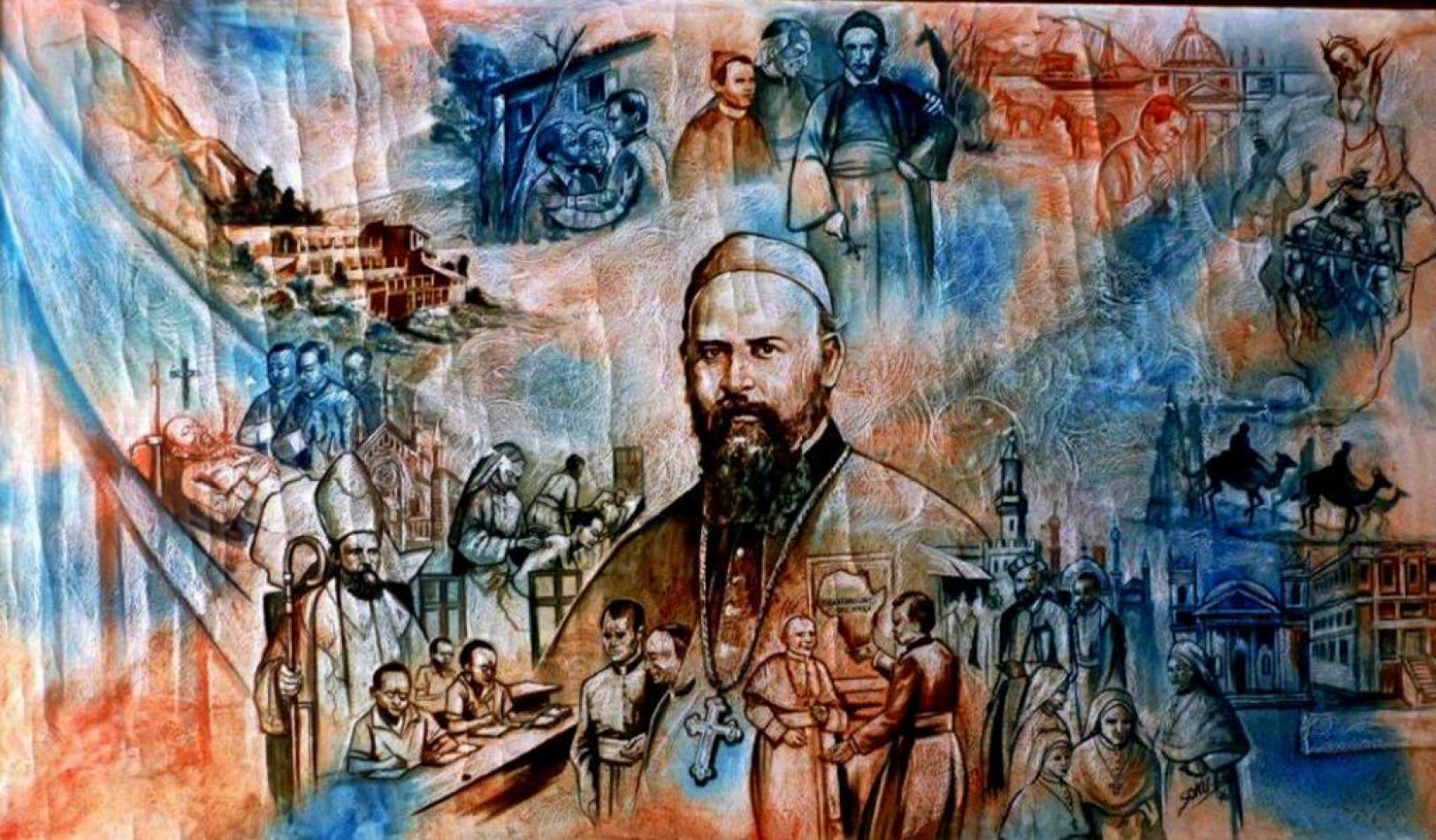

The missionary movement of the nineteenth century, the ecclesial humus in which the Comboni Institute was born and established itself (1872) was strongly marked by "the idealism of social transformation inspired by the Gospel. In the nineteenth century, the starting point was Christian experience, liturgy and sacramental life, in order to bring the Gospel to society and trigger the social and cultural transformation inspired by it"[33]. A winning perspective and challenge if we look at the optimism that drove so many Christians in Europe to become passionate about social transformation inspired by the Gospel and to bring the Gospel of Christ to Africa and Asia.

Daniele Comboni (1831-1881) sees his missionary initiatives, and the institutes he founded[34], in the light of a missionary plan[35] that seeks the regeneration of Africa with Africa; that is, a transformation of African society by Africans themselves and inspired by the Gospel and Christian life. Comboni sought an encounter with these peoples: he mapped the territory of the Vicariate entrusted to him, the geography and ethnic groups, the peoples and their languages[36]. His missionary expeditions included a significant number, sometimes a majority, of lay artisans and teachers of professions, in addition to priests; as well as women, missionary sisters, to respond to the challenges of social transformation, declined to women. And the model of missionary station that Comboni organises includes residences for priests, lay people and sisters, schools and workshops, the church and the catechumenate. The personality of the Founder and this model of "everything in the same physical space" favours the integration of evangelisation and social transformation but, after his death, it does not eliminate the natural tensions between the two impulses of the mission, evangelisation (as perceived in the epoch) and human promotion and, consequently, between ordained and non-ordained ministries.

This ministerial polarity, between ordained ministries (priests) and non-ordained ministries (brothers), has accompanied Comboni Missionaries history from its beginnings, with priests tending to "baptise first" and lay people (brothers, teachers) pushing for "civilisation first". It is a polarity that marks the turning points, the configurations of the Institute, such as the transformation into a religious congregation (in 1895) and the duplication of the Comboni heritage in two religious congregations (in 1922-1923: Sons of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, FSCJ, and Missionary Sons of the Sacred Heart, MFSC). While the MFSC promoted a more lay, secular mission, with an incisive role for the brothers who were more taken care of in their secular, professional preparation and more involved in the material management of the mission (and less taken care of in their spiritual religious preparation); the FSCJ promoted a mission more centred on the ordained ministry and more conformed to the spiritual dimension, where the priests were the protagonists and "took over" the direction of centres of formation and schools (the spiritual formation of the lay brothers was assured, but their professional preparation was less so).

This situation, as far as ministries are concerned, was reversed with the reform of the Council (General Chapter of 1969), which opened up new horizons for the brothers to be involved in the mission, embracing the ideal of the promotion of lay ministries (catechists, lay leaders, elders...), leading us to the situation we find ourselves in today, which sees ordained and non-ordained ministries equally involved in mission and evangelisation, each according to their own specificities.

It is appropriate to conclude this very brief summary of ministries in the Comboni Institute with three observations. First: until the 1969 Chapter, the involvement of the brothers in social transformation was carried out mainly in a context that we can call "institutional", that is, in the context of schools, colleges, technical schools, clinics and hospitals, children's towns and centres for the formation of leaders... Over the years, since the 1969 Chapter, however, the way has been opened to a more immediate involvement centred on projects, on forms of intervention on a more personal scale and with more immediate results; and the ability to support these structures, which require long periods of time and specialised preparation, has been lost at the Institute level.

Secondly, while up until the Chapter of 1969 the lay people involved in the Comboni mission were mainly the brothers (consecrated lay people), in the post-Council period the way was opened to the involvement of volunteers and lay people (non-consecrated), an opening that led to the birth of the Comboni Lay Missionaries. Moreover, the involvement of women in the mission changed paradigm after Vatican II; and, for us Comboni missionaries, after the 1969 Chapter, the relationship with the Comboni missionary sisters changed paradigm, under the sign of collaboration and the affirmation of feminism, of the increasing involvement of women in the life and mission of the Church.

Third observation: while up until the Chapter of 1969 and the current text of the Rule of Life[37], one speaks of work, profession, office and skills, witness to indicate the involvement of the brothers in mission and social transformation, today one speaks of social ministries, thus favouring the current trend, reflecting (at least in language, but not only... as we have seen above) a certain clericalization of the role of the laity (of the brothers) in the life and mission of the Institute.

These three changes have altered the context of the involvement of the laity in the Comboni mission and enriched the reflection on ministries.

7. Mission as service

The model of mission as service invites us to see ministries, both ordained and non-ordained, as gifts of Christ and His Spirit for the growth of the Church and for her "service to the person and the human family" as such (Gaudium et Spes, 92). We recall the Second Vatican Council because the model of mission as service has imposed itself especially in the post-Conciliar period, both in the Catholic sphere and among the churches separated from Catholic communion[38]: Christians make their contribution to social transformation and live their mission of service to humanity "exercising their professions with competence and fidelity" and working "as a leaven of the world in the family, professional, social, cultural and political spheres"[39].

In addition, the model of mission as service received a boost with the pontificate of Pope Francis who, particularly in the encyclical Fratelli Tutti, sees the Church and Religions at the service of the universal aspiration to fraternity[40] and, after describing the shadows of a closed world, the dreams that have been shattered, proposes the love that becomes concrete in service, according to the parable of the Good Samaritan (Lk 10,25-37).

This model of mission, in fact, is rooted in the movement of Jesus and in the Gospels, which show us Jesus very close to the people and attentive to their situations and stories, their needs. Jesus makes a proclamation and performs gestures, signs, which meet people's needs and bear witness to a new experience of God's sovereignty, as God's dream, to inspire all forms of society. "For the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many" (Mk 10:45), Jesus says of himself; and he entrusts to his apostles and disciples, as a testament, the commandment of love that manifests itself in service: "You call me Master and Lord, and say well, for I am. If therefore I, the Lord and the Master, have washed your feet, you must also wash one another's feet. For I have given you an example, that you should do as I have done to you. Verily, verily, I say unto you, a servant is not greater than his master, nor is a sender greater than he that sent him. Knowing these things, you are blessed if you put them into practice"[41].

The first community in Jerusalem is organised according to these criteria of Jesus and establishes deacons to serve at tables and meet the needs of the poor, orphans and widows. There is certainly a part of planning and idealism in the description of the first communities that Acts offers us, but it is evident that attention to the poor and service are part of the "DNA" of the early Christian communities and the conception of ministries. Paul speaks of his mission in the service of the Gospel and, in establishing and organising Christian communities in the Hellenic world, he does not forget the poor and the poor of Jerusalem (1 Corinthians 16). The Apostle to the Gentiles then offers the first theological vision of ministries in Christian communities and the demands of Christian witness in the world (1 Corinthians 12-14).

The history of the Church and of the Christian mission in the world (which we can only mention here) testify to this attention to the poor and this conception of a mission as service to humanity. With ups and downs, with limits and controversial aspects, a chain of hospitals, schools of all kinds, workshops and universities have given shape to a Christian involvement in the transformation of societies according to the values of the Gospel, from the Middle Ages to the modern age, up to our days, from Africa to Asia and the Americas.

The model of mission as service has proved particularly rich from the charismatic point of view, giving rise in the Church to a great variety of charisms and ministries in the fields of health, teaching and schooling, the promotion of human development and integral liberation. It has also revived the vocational motivation of many Christians, as a source of inspiration and a horizon of commitment to the regeneration of persons and the transformation of societies. In the history of the Comboni missionaries, this model has also proved to be a source of strong missionary motivation, from the Founder St Daniel Comboni (as we have seen) to the Comboni missionaries who today have embodied and lived this model of mission as service to life and humanity in an excellent way[42].

Lastly, the model of mission as service offers the possibility of sustaining a missionary presence in unfavourable conditions, when other models are not possible (such as schools and hospitals in the fundamentalist Islamic context); it is appreciated in societies in general and is also effective in fostering dialogue with other religions and cultures (particularly in the Asian context).

For all that has been said up to now, the model of mission as service also has what it takes to make the various models of mission fall into the temptation which besieges them: that is, to isolate itself from the other models, to think of itself in an exclusive way and to assert itself as unique or decisive; to stop dialoguing with the other models and to maintain itself in communion with them, losing sight of the Christian qualification of service and distancing itself from the source which guarantees its authenticity, in terms of witness, and its fruitfulness, in terms of evangelical effectiveness. The result of this situation is the reduction of mission to social action, the exchange of missionary work with humanitarian work, which opens up confusion between the action of the Christian mission and the action of non-governmental organisations and reduces the Church to an NGO[43].

8. The knots to be verified

The collection of current initiatives in the field of social ministry and within the Comboni Family, with the direct testimony of their protagonists and inspirers, offers an overall view and an updated panorama of ministry in the Comboni Family. The title[44] and the spirit of the collection may be considered not exempt from a certain amount of self-referentiality, but the work remains as a point of reference and compulsory reading for a reflection on ministries in the Comboni Institute. The theological, biblical and pastoral reading, offered at the beginning of the collection of the initiatives by continent, helps to embrace the various initiatives with an overall look and understanding, which is necessary to understand the individual experiences and evaluate their significance in the context of the journey of the Comboni Family and the Church today.

The mapping of social ministeriality in the Combonian Family, promoted by the Commission for Ministeriality in the Comboni Family[45], completes the collection and adds a tool for an overall and in-depth vision of the involvement in social transformation on the part of the members of the Comboni Family, of the Comboni Institute in particular, to refer to the title we adopted at the beginning of our text. As has been pointed out (by someone sharing in the groups), a more critical reflection is needed regarding the motivations and objectives of involvement (to use an image that has been mentioned: do we work only to teach the person to fish, instead of giving him the fish? or is there another motivation and an objective beyond that, at the root of involvement and the exercise of social ministry?).

In order to contribute to this reflection, we offer, by way of conclusion to this article, some ideas on the knots that need to be checked. The first would be that of competence and professionalism (which also emerged in the presentation of the mapping) of skills. Today, in order to get involved and intervene in the social sphere (economy, politics, education, etc.), skills are needed. Not only in the field of education and health, where formal and specific studies and a professional diploma are required. But even in more informal spheres, such as popular education, helping to promote and improve living conditions (wells, water, health, informal work, integral ecology, etc.), specific and legal skills are required, and personal feeling and creativity, a more or less evangelical impetus, are no longer enough.

In the past, even the recent past, there was a tendency to consider the charism and personal sensitivity as sufficient to justify the initiative of individuals in the field of social transformation. But today, out of a sense of responsibility towards the Institute and towards society (and the people we are supposed to be serving), this can no longer be accepted, and there is a need for a supervisory body (the authority in the Institute and in the Church), which takes on the task of verifying and discerning ideas, proposals, individual initiatives, and of evaluating the implementation of projects and the development of initiatives, proposing a code of engagement and procedures to be followed. The establishment of the Institute for Social Transformation in Nairobi[46] has given the Comboni missionaries the opportunity to ensure and support, in the candidate brothers, the skills for a renewed quality of commitment in the social field.

The second issue to be clarified is the frequent encroachments, when we speak of involvement in social transformation, especially by ordained ministers who think that the imposition of hands makes them suitable for any kind of intervention. Comboni priests tend to invade the field of their brothers, lay people and non-ordained ministers, considering themselves prepared for every type of intervention. It is expected that the present reflection on ministries in the Institute will also clarify this problem of encroaching fields and help to clarify the different roles of non-ordained and ordained, social and/or other ministries.

The third issue to be clarified is the question of the return expected from interventions and involvement in social transformation. While with traditional structures (schools and colleges, clinics and hospitals) a medium to long term return was expected and generational transformations were aimed at, today, with projects and small interventions an immediate, more subjective return is aimed at. Involvement becomes more personal and affective and a return is expected which is emotionally compensatory and tailored to the motivations.

This level must be verified, not least because situations can arise in which the expectations of the promoter and manager of the project do not always coincide with the expectations of the people, due to the loss of the ability to listen and verify.

The fourth issue to watch out for would be the (always possible and sometimes obvious) mystification of initiatives, the absolutization of an experience and its affirmation as a master or model experience. The way in which they are presented tends to absolutize them, as if experience, which has an undeniable value in its context, were the key to solving global problems... forgetting that social problems are complex, constantly evolving, depending on local and global variations, ranging from health (see the current situation with the virus) to the economy and finance, forgetting that we Christians, as the Church has always affirmed, do not have a technical solution to the problems of the social sphere, but only a Gospel to be dropped into them as transforming yeast. It is necessary to maintain a spirit of vigilance in order to recognise the limits of current experiences and to be able to arrive, each time and at every turning point, at the conclusion that "the most precious service that the Church can give to humanity is the offering of the Gospel of Christ"[47].

What has been said above leaves the Comboni Institute with the task of developing and offering its members a spirituality that supports the exercise of ministries, as a humus and source of fruitfulness; and thus, counteracting the tendency towards spiritual disbandment that particularly threatens the exercise of ministries in the social and political spheres. Daniele Comboni is a source of inspiration in this search for a spirituality for ministries, in proposing to priests, nuns and lay people, a spiritual foundation for apostolic action: "The missionary, who does not have a strong feeling for God and a lively interest in his glory and the good of souls, will lack aptitude for his ministries, and will end up finding himself in a kind of emptiness and intolerable isolation"[48]. In the search for an integration between spirituality and apostolic activity, he uses two concepts, holiness and ability, which should be recalled here: "... holy and able. One without the other is worth little to those who pursue an apostolic career. (...) Therefore, first of all saints, that is, completely free from sin and offence to God and humble. But this is not enough: we need charity that enables our subjects"[49]. Therefore, charity (divine agape) at the root and inspiration of capability and professionalism.

9. - Ministries and the abuse crisis

I have resisted so far including in this reflection on ministries a note on the phenomenon that in our time has engulfed ministries in the Church, both ordained and non-ordained, in an endless storm. I am referring to the crisis of abuse (sexual and other, by priests and bishops, cardinals...) that has received so much publicity in our day. I thought I would not mention this situation, because we all know it, in the shame and perplexity it has caused everyone. But then I thought that we could not reflect on ministries without mentioning this issue; that is, to put it in positive terms, without talking about the responsibility inherent in the exercise of a ministry, whether ordained or not, in the Church and in the Institute, and of the consequent abuses and failures.

The present crisis has led us to understand, to our cost and suffering, three aspects that need to be recalled: firstly, that it is not enough to invoke the charism, the gift received by grace or had by nature, to exercise a responsibility or service in the Church and society; secondly, that recognition, by the authority in the ecclesial community, or the approval of the civil authority, is not enough for the exercise of a ministry, of a service (discernment is subject to error or pressure of interests); thirdly, it is also and always necessary to have a sense of personal responsibility, towards the Church and society, of those who are about to exercise a charism (even when recognised and/or accepted).

Today in society there are laws and regulatory codes for the exercise of professions and services. Also, in the Church, as a positive consequence of the crisis, codes of conduct for the exercise of ministries have emerged, making the general order of the Code of Canon Law concrete.

The Church's response to the crisis of ministries has been diluted over time and is still ongoing, with new attempts at response, such as the announced holding of an international congress on the priesthood by the Congregation for Bishops (to be held in Rome from 17 to 17 February 2022). For some observers, this management of the crisis on a day-to-day basis is clearly insufficient and more is needed: a general synod on ministries is needed (it is not clear why, in the process of preparing the 2018 general synod, the idea of a synod on priests was mooted and then the decision was taken to hold a synod for young people, once again leaving the current crisis of ministries in the Church unanswered).

At this point, a look at the abuses in the Comboni Institute is also necessary. Two observations must be made in this regard. The first is clearly positive: at the level of principles, the Comboni Institute has responded well to this need for accountability in the exercise of the ministry, which has emerged in the context of the crisis of abuse. In fact, the Institute was among the first, following the General Chapter of 1997, to set in motion the process to prepare the Code of Conduct, which is now approved and followed, both at the general and provincial levels.

When we think of abuses in the Church, we think of those perpetrated by ordained ministers. However, it must be stated that responsibility in the exercise of ministries concerns ordained and non-ordained ministers alike, as well as those now called social ministries. The seal of confession does not impose itself on these, and a more transparent and professional approach can and must be taken (as mentioned earlier, in number 8, in the fourth point). The involvement of Comboni missionaries in the social and political spheres requires discernment and supervision, because of the tendency of this involvement to define their own status, exempting itself from common rules and procedures in the Institute, creating situations of exception which can evolve into situations of abuse (for example, towards common rules and towards the discernment of authority; but the situation can also occur in the economic sphere and in the use of money, an area in which there can be a lack of responsibility towards the Institute and towards others in society).

Conclusion: antidote and promise

I would like to recall, by way of conclusion, a word of the Lord Jesus which, by force of circumstances, must be of his programmatic manifesto, the Sermon on the Mount: "You are the salt of the earth; but if salt loses its savour, how can it be made salty? You are the light of the world; a city cannot be hidden on a mountain, nor a lamp lit to put it under a bushel" (Matthew 5:13-15). And then he adds: "Let not your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your gift may remain secret; and your Father, who sees in secret, will reward you" (Matthew 6:3-4). I evoke this word of the Lord as an antidote to every drift of self-referentiality, to every temptation to manipulate and instrumentalize situations for every good purpose, which we can always fall into, especially in the area of social and political involvement. I evoke, above all, this word of the Lord as a promise of fruitfulness and fullness of meaning for one of the most demanding and difficult ministerial areas of the Comboni and Christian mission, which is precisely the social one.

Fr. Manuel Augusto Lopes Ferreira, mccj

Rome, Pentecost 2021

[1] Il Grande Dizionario Italiano, Hoepli, 2008, Milan. Also Dizionario Enciclopedico Universale, Sansoni, Florence 1995. Not even the Dizionario delle Idee, Sansoni, Florence 1977, mentions it. The word ministry comes from the Latin ministerium, "service, office, charge".

[2] Nuovo Dizionario di Teologia, by G. Barbaglio and S. Dianich, S. Paolo Edizioni, Rome 1988, pp. 902-931. Interdisciplinary Theological Dictionary, Marietti Publishers, 1982, pp. 532-541, text by S. Dianich. Dicionário Biblico-Teológico, Edições Loyola, pp. 275-296, text by O. Karrer and J. Gewiess. Dictionary of Biblical Theology, by Xavier Léon-Dufour, Marietti, 1980, pp. 686-689, text by P. Grelot.

[3] New Dictionary of Spirituality, San Paolo Edizioni, Milan 1999, pp. 954-971, text by S. Dianich.

[4] Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Spirituality, Città Nuova, Rome 1990, vol. II, pp. 1599-1605, text by P. Scabini. Dizionario di Spiritualità dei Laici, Edizioni OR, Milan 1981, vol. II, pp. 31-40, text by Francesco Marinelli.

[5] Guido Oliana, La teologia e spiritualità di San Giuseppe e la vocazione del fratello missionario comboniano. Paternity, fraternity and ministeriality, pp. 15-16 of the text distributed by the author in PDF format.

[6] X. Léon-Dufour, Dictionary of Biblical Theology, Marietti, Genoa 1994. Ministry, pp. 686-689.

[7] Idem.

[8] Dictionary of Missiology, PUG, EDB, Bologna 1993. Ministries, pp. 338-339.

[9] Dictionary of the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, UNEDI, Rome, 1969. Ministries and Ministry, pp. 1391-1415.

[10] Documents of Vatican II, Lumen Gentium, n. 10; the whole of chapter IV, nos. 30-38 is dedicated to the laity.

[11] Documents of Vatican II, Lumen Gentium, n. 12.

[12] Documents of Vatican II, Gaudium et Spes, n. 26.

[13] Documents of Vatican II, Gaudium et Spes, n. 43.

[14] Documents of Vatican II, Lumen Gentium, 31.

[15] Documents of Vatican II, Lumen Gentium, n. 38.

[16] Documents of Vatican II, Lumen Gentium, n. 31.

[17] Documents of Vatican II, Gaudium et Spes, n. 3.

[18] Documents of Vatican II, Apostolicam Actuositatem, n. 3.

[19] Documents of Vatican II, Apostolicam Actuositatem, n. 2.

[20] Documents of Vatican II, Apostolicam Actuositatem, n. 3.

[21] Documents of Vatican II, Apostolicam Actuositatem, n. 5.

[22] Documents of Vatican II, Ad Gentes, on the Missionary Activity of the Church, n. 12.

[23] Documents of Vatican II, Apostolicam Actuositatem, n. 20.

[24] Julius Kambarage Nyerere (13 April 1922 - 14 October 1999), President of Tanzania from 29 October 1964 to 5 November 1985.

[25] Documents of Vatican II, Conciliar Decree Christus Dominus, on the Pastoral Office of Bishops.

[26] Documents of Vatican II, Council Decree Optatam Totius on priestly formation; and Presbyterorum Ordinis on priestly ministry and life.

[27] Luca Diotallevi, Il Paradosso di Papa Francesco, La secolarizzazione tra boom religioso e crisi del Cristianesimo, Rubbettino, 2019.

[28] The situation of the Church in Germany, for some, would be emblematic of what is being claimed. In this country, where the Church is the second largest employer, after the State, the lay leaders who mark the path of the Church (currently in Der Synodale Weg) are officials of the Church, in which they exercise a profession, with their own rights and in their own requests, rather than being witnesses in the world where they live out a charism received as a gift of the Spirit.

[29] Chiara Giaccardi and Mauro Magatti, La scommessa cattolica, Il Mulino, 2019.

[30] In this sense go the significant documents of the pontificate: Evangelii Gaudium, Laudato Si', Fratelli Tutti.

[31] Pope Francis, Without Him we can do nothing; Being missionaries in the world today", Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2019. On the concepts of the Pope's proposal, see: Francesc Torralba, Dizionario Bergoglio, le parole chiave di un pontificato, Rome 2019; the author considers the vocabulary of Pope Francis' social magisterium.

[32] See, for example, Pope Francis, Address to Participants in the Plenary Assembly of the Pontifical Council for the Laity, 17 June 2016; Evangelii Gaudium, 27-30.

[33] Manuel A. L. Ferreira, The Missionary Institutes in Europe, Rome 2019, p. 4 of the PDF edition.

[34] Istituto dei Missionari Comboniani, Verona 1867; Istituto delle Suore Missionarie Comboniane, Verona 1872.

[35] Daniele Comboni, Plan for the Regeneration of Nigrizia, Rome, 1864.

[36] An example of this methodology is the expedition to Cordofan and the Nuba mountains, carried out before his death and described in letters written in April and May 1881. See Archivio Comboniano, Year LI, Rome 2021, pp. 23-192.

[37] Rule of Life, 11; 11.1 and 11.2; 58.4; 61.

[38] The ecclesiology that sees the Christian mission as service to the world and its transformation and liberation is present in important post-Council documents such as the Uppsala Report of the Ecumenical Council of the Church (1968), the Conclusions of the Second General Conference of Latin American Bishops in Medellin (1968) and the document that came out of the 1971 Synod of Bishops on Justice in the World (November 1971).

[39] Justice in the World, 1971 Synod, Chapter II.

[40] Pope Francis, Brothers All, nos. 271-284, 9-55 and 56-86.

[41] John 13, 13-17 and, in parallel, Mark 10, 41-45, Matthew 20, 24-28 and Luke 22, 24-27.

[42] Examples include Giuseppe Ambrosoli and Elio Croce, in the field of health; Ezekiel Ramin, in the field of liberation and justice.

[43] Pope Francis has recalled this risk on several occasions. For example: Without Him we can do nothing, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, Rome 2019, p. 73.

[44] Commission on Ministeriality in the Comboni Family, We Are Mission: Witnesses of Social Ministeriality in the Comboni Family, edited by Fernando Zolli and Daniele Moschetti, Rome 2020.

[45] Presented during the second webinar session, 5-6 March 2021, and available at www.combonimission-net.

[46] L’Institute for Social Transformation integrates the School of Arts and Social Sciences of the Tangaza College in Nairobi, Kenya. Fr. Francesco Pierli, mccj, is its funder and inspirer.

[47] The Latin American Bishops' Conference in Puebla affirmed that 'the best service to one's brother is evangelisation, which disposes him to realise himself as a child of God, liberates him from injustice and promotes him integrally'; Puebla Documents, No 3760 (1145).

[48] Daniele Comboni, The Writings, 2698.

[49] Daniele Comboni, The Writings, 6655, 6656.