Daniele Comboni

Missionari Comboniani

Area istituzionale

Altri link

Newsletter

Monday, May 12, 2014

The pioneering missionary figure of Gondokoro, Fr. Angelo Vinco, stands out as really fascinating and inspiring. To underline his exceptional personality from the start it is worth mentioning the fame that he acquired among the Bari, who called him the “son of thunder”, as Comboni attests, or juok (diviner, a man of the spirit), as Vinco himself writes in his Diary (1851-1852)… (Fr. Guido Oliana, MCCJ).

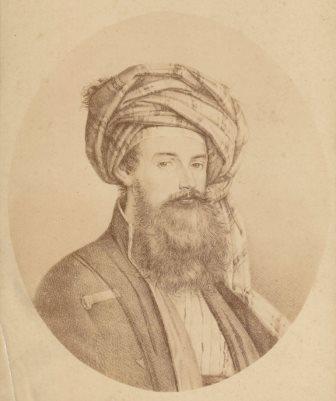

Fr. Angelo

Vinco.

Fr. Angelo Vinco,

the pioneering missionary of Gondokoro,

inspirer of Daniel Comboni

The pioneering missionary figure of Gondokoro, Fr. Angelo Vinco, stands out as really fascinating and inspiring.[1] To underline his exceptional personality from the start it is worth mentioning the fame that he acquired among the Bari, who called him the “son of thunder”, as Comboni attests, or juok (diviner, a man of the spirit), as Vinco himself writes in his Diary (1851-1852). In a perhaps exaggerated way, Cardinal Massaia, the Apostle of the Gallas in Ethiopia, compared him to St. Francis Xavier, showing the extraordinary impact Vinco had on people. When Vinco died, the Bari population paid him honour with a royal funeral and mourned him for eight days. Songs about him were composed and sung for many years after his death. Abuna Vinco was the inspiring source of the vocation of the young Comboni, when in Verona he first encountered and heard him speaking so passionately about his missionary experience in the Sudan.

1. Fr. Angelo Vinco: from Verona to the Sudan

Fr. Angelo Vinco (1819-1853), from the diocese of Verona (Italy), reached the Sudan with the first missionary expedition in 1847 led by the Polish Jesuit Fr. Ryllo as Pro-vicar.[2] The Apostolic Vicariate of Central Africa had been established by Pope Gregory XVI the year before.[3] The group arrived in Khartoum the following year. Ryllo died in the same year. At the time Khartoum counted about 15.000 people. It was a market place of thousands of slaves. Some of them were ransomed by the missionaries, who brought them to the mission and began to instruct them.[4] At the end of 1848, due to the serious financial problems of the mission of Khartoum, Fr.Vinco went back to Italy to plead for help. He arrived in Verona on January 19, 1849. There he spoke passionately about his missionary experience.

Fr. Vinco made three journeys on the White Nile up to Gondokoro (Juba) (1849-1853). The first journey was from the end of 1849 to 1850. Members of this first expedition were the new Pro-vicar Knoblecher, diocesan priest from Jugoslavia, who had studied in Propaganda Fide with Fr. Vinco, and the Jesuit Fr. Emanuel Pedemonte. Both Knoblecher and Pedemonte gave a report of their first exploration.[5] The second journey was in 1850-1851, of which we have the account that Fr. Vinco gives in his diary.[6] The third was in 1852-1853. Fr. Vinco died in 1853.

2. Fr. Angelo Vinco inspires Daniel Comboni

In his return to Europe in January 1949, just one year after his arrival in the Sudan, Fr. Vinco spoke about his first missionary African experience before 500 students of the Mazza Institutes of Verona, of which he was a former student. Among them there was Comboni, who was then 17. Fr. Vinco - Comboni reports - spoke

with the full fervour of his soul a number of very interesting details. [...] He kindled in them the passion of divine charity that cannot be assuaged except in the career of complete dedication and sacrifice for the salvation of the infidels. Fr. Angelo Vinco’s accounts made a great impression on the ardent spirit of that marvel of charity and wisdom, Fr. Nicola Mazza, [...] [who] decided to cooperate in the apostolate of Africa.[7]

Comboni tells how he felt motivated to dedicate his life to the African mission.

In January 1849, a 17-year old student I promised at the feet of my most reverend Superior Fr. Nicola Mazza to dedicate my life to the apostolate of Central Africa; and with the grace of God it has never happened that I have been unfaithful to my promise. I then began to prepare myself for this holy undertaking.[8]

3. First journey of Fr. Vinco on the White Nile (1849-1850)

Fr. Vinco returned to Khartoum from Italy in October 1849. The journey up the White Nile began on November 13, 1849. The missionaries, the Pro-vicar Ignaz Knoblecher, Fr. Emanuele Pedemonte and Fr. Angelo Vinco, left Khartoum, passed through the Schilluk, Nuer and Dinka lands and approached the Bariland on December 25.

The Bari were described by Fr. Pedemonte as “more sociable than the preceding tribes [...]. Their character is happy and care-free. These people, too, feared abduction and hid their boys and girls.”[9] He recognized that they are “the most courteous of all the native people living the rivers banks.”[10] Hence it was decided that Frs. Pedemonte and Vinco would study the possibility of a foundation among the Bari. Fr. Vinco was to study the geographical nature of the country and Fr. Pedemonte was to look for a place to build their residence while applying himself to agriculture. They were welcomed by the two brother sons of a chief (actually a rain-maker): Shoba and Nyigilò.[11] The latter came to know the work of the missionaries in Khartoum and developed with them “a long-standing friendship.”[12]

The Turks, commanders of the boats and other traders on behalf of the Pasha (governor) of Khartum, tried to convince the populations not to trust the missionaries and scared them saying that the missionaries - as Knoblecher reports - were “cannibals, incendiaries, and sorcerers with the power to withhold the rain and wither the grass.” [13] The same is told by Pedemonte, who writes that the Turks were trying to convince the naive and credulous Bari chiefs that the two missionaries [Vinco and Pedemonte], who were supposed to settle in Bariland, were “two evil sorcerers who would have stopped the rains on their soil, thus depriving them of their durra for food and drink, and their pastures” and that “as soon as the food became scarce in his country”, [they] “would feed on the flesh of their children.”[14] Vinco himself writes: “The Turks had told the people here that, if we remain among them, their animals would die, the rain would stop, the vegetation would wither and perish, and what was more terrible, many of the people would die.”[15] The result was that when people saw any boat approaching the bank of the Nile, “women, girls, boys and cattle were running away inland for safety.”[16]

The missionaries had really to struggle to convince people that they had good intentions and wanted their real welfare. They gave them gifts (mainly in form of coloured beads) to appease the chiefs and through them their populations. The Pro-vicar Knoblecher even played the accordion. People were astounded. “They attentively followed the movements of the hands and fingers, and they would have liked to know how such pleasing and measured sounds were possible.”[17]

Due to the slanders of the Turks, which were confusing the feelings and attitudes of the various populations towards the missionaries, before deciding to settle in the area the Pro-vicar Knoblecher wanted to make sure - in his words - of “the freedom and the independence of the Mission from our sworn enemies the Turks.”[18] The situation was not easy for the missionaries, because they were confused with the traders, among whom there were also slave-traders. Taking into account the infelicitous circumstances, the missionaries “sadly [...] decided that it was impossible to establish themselves among these people on this trip. On the same day, 21 January, they left for Khartoum.”[19]

4. Second journey of Fr. Vinco on the White Nile (1851-1952)

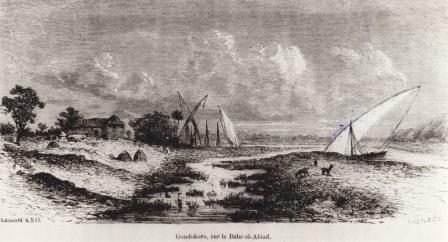

Fr. Vinco made a second journey, this time alone, on the White Nile. He reached the Bariland in autumn 1850 and in 1851 opened the mission at Gondokoro.

The situation of Kondokoro by the mid 1840s at the time of Fr. Vinco’s pioneering missionary work among the Bari is described by historians in quite dramatic terms. There were two groups firmly established: on one side, the missionaries; as on the other, the Arab traders from Khartoum, who also indulged in the slave trade. They were “at each other’s throats,” drawing local chiefs and people to their support. The chief Subek-lo-Logonou supported the slave traders, aided also by the white trader Alexandre Vaudey, who in 1851 in Khartoum became Vice-consul of Sardinia (Italy). The Bari son of a chief, Nyigilò, who had been in Khartoum and saw the work of the missionaries, supported the missionaries. On the side of the missionaries there was also the Savoyard trader Brun-Rollet who fought slavery.[20]

Comboni reports on Vinco’s apostolate as follows:

In short time, Fr. Vinco learned the language of the country, painstakingly visited many places in the Bari south-east of Gondokoro. In the hope that the missionaries would follow to settle, he began a true apostolate among those people. His patience, his self-denial, his gift of charity and above his courage, soon made him the most important and venerated man in the country. He started teaching children; he baptized many in “articulo mortis”, and prepared the villages properly to receive the Missionaries with true love.[21]

Comboni narrates an episode about the courage of Fr. Vinco that made him a legend among the Bari. He managed to tame a lion that was threatening and devastating the area.

In one Bari village an enormous lion was devastating the area and devouring people, especially children. Being used from his youth to hunting in the mountain of Cerro [Verona], where he was born, he managed with great effort and trusting in God to kill the terrible animal with a rifle. It is impossible to imagine the cries of joy and the gratitude he inspired in those people who called him “son of thunder” and brought him oxen and many gifts as a sign of extraordinary veneration. His name was famous among the Africans.[22]

In the Historical Outline of the African Discoveries of 1880 to the Rector of the African Institutes in Verona, in which he shows an extraordinary acquaintance of the history and geography of all explorations of Africa of his time, Comboni reports that “Fr. Vinco in 1851 was the first European to have stayed so long on the White Nile at that latitude.” He studied the climate, the nature of the country, travels round also to visit other tribes, studied their languages, customs and character.[23] Fr. Vinco collected information about “the unexplored stretch of the Nile, its tributaries and the people who inhabited the equatorial regions of its sought after sources.” In 1852 he even tried an expedition among those populations.[24] “Vinco travelled further South than anybody before him.”[25] He reached beyond Nimule and visited most probably parts of the Acholiland and Madiland in the present Uganda. He was the first European who at that time reached so far in the effort of discovering the sources of the Nile.[26] Fr. Vinco himself says: “Even since I had decided to remain among the Bari I has also made up my mind to try and discover the source of the White Nile, and this end left nothing undone.”[27] Again: “I was very anxious to visit these tribes and discover the source of this river.”[28]

In the middle of 1852, from the interior of Bariland Fr. Vinco returned to Marju, a large Bari village on both banks of the Nile (now disappeared). In Marju, Fr. Vinco found the news that the Mission of Khartoum wanted him as soon as possible in Khartoum, where he arrived on the 11th of June 1852. He was received in a rather cold manner because of the heineous slanders spread about him with the result that he was considered the cause of the difficulties that the mission in Central African was undergoing. Only his friend Brun-Rollet, who was the only true witness of what Fr. Vinco had actually done among the Bari, truly supported him. Fr. Vinco defended himself against the slanders with a hearthy letter dated August 9, 1852 and addressed to the Cardinal Prefect of Propaganda Fide.[29]

5. Fr. Vinco’s third journey and untimely death

Fr. Vinco remained in Khartoum very shortly. Soon he left for the third and last journey to the Bariland.

Comboni states that Fr. Vinco in 1853 was struck by fevers before accomplishing his plan of explorations of the sources of the Nile.[30] Certainly his weakness was also due to the psychological harassment of the chiefs, manipulated by the Arab and non-Arab slave traders. As an author states, Fr. Vinco died prematurely due to the conflicts with the group supporting slavery with the Bary-chief Subek and the trader Alexander Vaudey. His death was “a result of stress caused by the continuous harassment and intrigues of Vaudey and the slave traders and their Bari allies.”[31] No surprise, because it is a common experience that malaria and other fevers find a vulnerable prey when a person is weak both psychologically and physically.

On January 3, Fr. Knoblecher with other three missionaries reached Gondokoro. Assisted by his colleague missionaries, Fr. Vinco died on January 22, 1853 at the age of 33. He was given a royal Bari funeral. He was buried in the middle of Marju, a section of Ilibari. Fr. Vinco’s friend the trader Brun-Rollet in 1855 writes that over “3000 to 4000 came to wail at his tomb and eight days of morning were observed.”[32] There was a touching detail. Mr. Alexander Vaudey himself, who was a major cause of distress for Fr. Vinco, helped in digging his grave. He repented and publicly asked the dead Fr. Vinco for forgiveness.[33]

6. Fr. Vinco’s Missionary Apostolate according to his Diary (1851-1852)

I would like to revisit Fr. Vinco’s apostolic journeys through his own diary. Fr. Vinco was firmly convinced that good relationships with people were essential conditions for his missionary apostolate. He tried his best to gain the confidence and affection of people to counteract the slanders of the Arab traders of Khartoum and their European supporters, who did not want any contact between the Catholic missionaries and the local populations. His strategy was to befriend first of all the chiefs, in the conviction that in this way he would attract the benevolence also of the various populations.

Before he reached the Bariland, he passed through the land of the Schilluk, Nuer and Dinka. In order to show the nature of Fr. Vinco’s apostolic commitment, I would like to highlight an episode of his courage and concern about establishing good relationships with people.

As soon as the boat was approaching the bank of the river where a group of Nuer was, Fr. Vinco saw that all run away as soon as the boat was approaching. These people feared that the ship belonged to the Turks interested in slave-trading. To show that they were not the ones, Fr. Vinco threw some colourful beads to them and through an interpreter told them to approach him without fear, because he did not have any bad intentions. The crew discouraged him to approach the Nuer saying that they were very fierce. Fr. Vinco insisted that he wanted to meet them. Then they called for him the chief Kan. Fr. Vinco talked to him peacefully and befriended him by offering him some glass necklaces. The chief was so pleased that he told Fr. Vinco: “I will consider you traitor if you do not pay me another visit on your return, provided, of course, that you are not accompanied by Turks with whom I want no dealings.” Then they blessed him “using a vessel filled with ox-urine and water”, in which the most important people spat and asked Fr. Vinco to do the same. Fr. Vinco writes:

It filled me with great joy to think that I had been received with such a great kindness because, in view of the warnings I had previously received, I had really expected troubles. I felt encouraged to carry out what I had undertaken, despite the fact that I was alone and with scarcely any means of defence in case of attack. I had refused to join a government expedition [i.e. the annual trading expedition], as I was certain that the Turks would have once more upset all my plans, as they had done on previous expedition.

Fr. Vinco intended to settle among the Bari, but he was completely alone and felt anguish, because he then did not know well the language and felt harmless among those possibly violent tribes. He felt the temptation to go back to Khartoum. Yet he had a strong desire to remain among them:

I cannot express the anguish I felt. I could see myself being forced to turn back and, what was more important to me, I would have been unable to remain among the Bari [...]. However, I trusted myself to God, and without further meditation I gave order to set sail, and the voyage continued.[34]

On 14 February 1851 he arrived in Marju. There he spent eight or ten days while waiting for his friend Nyigilò. Fr. Vinco took the chance to get to know the chief Jubek, the most feared rain-maker. This man used to receive many gifts from people, like numerous heads of cattle in payment for the gift of rain, less their cattle and the people die because of draught. Fr Vinco befriended him. He writes:

I cultivated his friendship by making him daily gifts of beads, and continually yawa, milk, sesame, and many other things I could find for him and his family, especially when I became aware of the supreme authority he wielded among the people. In addition I presented him with a suit of clothes and I had the satisfaction of knowing that he was very pleased, and was presenting me in favourable light among the people.[35]

On March 4, 1851 Fr. Vinco arrived at Belinyan, in the interior of Bariland (the present area of Gumbo Catholic Parish run by the Salesians Don Bosco), where he wanted to explore the mountain, while staying in the house of his friend Nyigilò. He narrates his first encounter with the people at Belinyan, who had never seen a white man before. On the advice of Nyigilò some shots were fired in the air to announce the arrival of the exceptional guest. He took residence in the house of Nyigilò, where people brought immediately some pots with water and merissa. He wanted to rest a little bit because he was tired of the journey, but people were eager to see him. Fr. Vinco writes in his diary:

A huge crowd gathered eagerly waiting for a glimpse of the newly-arrived white man. They jostled and pushed one another in an attempt to greet me first. Some seized my hands and held them high, some danced before me, whilst others shouted ta doto homonit (“I greet you, new traveller”). Some laughed at my colour and others, noticing my beard, went so far as to call me agueron, man-eater.[36]

After resting the first night, the following day “the visits started all over again, and I had to exchange greetings and compliments without showing any sign of impatience.” While the day before people had come empty-handed, that day they began to bring some gifts, such as merissa, milk, honey, roasted sesame, meat etc. They offered these gifts in order to get something in exchange, i.e. beads.[37]

On the third day Fr. Vinco felt that it was his turn to pay visit to the leading personalities of the village, who had come to visit him the day before, among whom Jubek, Tongun and Doka.

With kind words and gifts I tried to gain their favour, and was quite successful, as I was now able to express myself reasonably well in their language (Bari). In the meantime, the news of my arrival spread like wildfire to all the surrounding villages. Many of the inhabitants came to see me, and in a short time I had the opportunity of meetings the chiefs of Gedian, Uagnan, Pacer, Mogri, Godian, Duer and other places, and I endeavoured to gain the confidence of them all. I remained there for about 20 days, doing my utmost to lay the foundations of my plan, that is, to find out whether it would be possible for me to stay among them.[38]

Fr. Vinco decides to remain among the Bari and to send back to Khartoum the ships that had brought him. Fr. Vinco describes his feelings in this new situation. “I must confess that, at this moment, I was assailed by many varied thoughts as to my future, but trusting implicitly in God, I succeeded in regaining my tranquillity.”[39]

But where in his explorations he was not known people feared him. He writes:

While passing through the various villages, I was afraid of being attacked, as all the inhabitants looked at me suspiciously, and ran away from me as if I were a wild beast. I then realised that my safety was not yet assured, but I took courage and continued on my way.[40]

Fr. Vinco felt more at peace in Belinyan. His main concern now was to study seriously the language and their customs of the people, as he writes, “so as not to make a false step, because all my future depended on the impression I created during the early part of my stay.” He had to put up alternatively with the insults and the compliments of the people, but eventually with satisfaction Fr. Vinco says:

This state of affairs did not last long, and slowly the people became accustomed to my face and dropped all uncomplimentary remarks. Moreover I was beginning to be held in higher esteem; they spoke well of me on all occasions, treated me with greater respect and consulted me in their public and private affairs. They went so far to call me Juok, the name of one of their gods, who, according to them, lives in heaven.[41]

Fr. Vinco reports a discussion in a gathering of the chiefs about the problems of rain. People had threatened Jubek that, if he had not produced rain in three days, they would kill him. Fr. Vinco greeted them with the customary greeting Ta dotore and sat among them. After a ceremony oxen were slaughtered as sacrifice for the rain and some other making-rain-rituals had been performed by the chiefs and one of their priests (bonit). It was stated that rain would fall on that same day. Fr. Vinco narrates that he stood up holding a forked stick in his hand as is customary with their speakers and addressed them.

Fr. Vinco tells that he spoke boldly to the crowd before the feared chief Jubek about God as the loving creator, who brings rain and all good things, but on the condition that people stop quarrelling, waging wars, killing and stealing. He quoted the Golden Rule: “You must not to others what you would not have them to you.” Fr. Vinco highlights that people were surprised by his message, which they considered good, but especially they were full of admiration for him because he spoke fearlessly in front of Jubek.[42] He addressed them more or less in the following way. Fr. Vinco himself reports the following catechesis:

Bari, as you have been so good as to receive me among you, and honoured me with the invitation to be present at one of your tribe's most sacred ceremonies, grant me leave to speak freely to you. I do not intend to offend anybody, but I simply wish to bring forth the naked truth, as it is for this very reason that I have been placed among you by Heaven. The God, who created me and you, also created the sun, the moon, the stars, your cattle, trees and rivers. The same God makes the grass and seeds grow - in other words, the same God who from nothing created everything in heaven and on earth. Although this great God is, as yet, not known to you, and, therefore, not honoured and served by you, He nevertheless loves you and helps you in a thousand different ways. This is the God who makes the rain fall, thus preventing your fields from being scorched; He keeps you in good health; He multiplies your cattle; He gives you the strength to overcome your enemies; in short His love for you is greater than that of any father or mother for the sweetest and most cherished son. Hence, if you wish the rains to fall on your fields, you must desist from the quarrels and wars which rage continuously among you, and must stop killing your fellow-creatures. You must refrain from theft and robbery, and must not give way to wantonness; in other words, you must not do to others, what you would not have them do to you.

Fr. Vinco comments on the effects that his words had on people:

The people were astonished at the unexpected tenor of this speech, the like of which they had never heard before. Despite this, everybody including the chiefs, the people and Jubek himself, warmly applauded me, saying that my reasoning was sound and that what I had said must indeed be true. My speech was particularly welcomed by the people, who above all admired me for having thus spoken before Jubek himself, as each year they had to hand over many oxen to him, in his capacity as rain-maker.[43]

Fr. Angelo Vinco became famous also as a peace-maker among the various tribes. The chief of Lirya and three Lokoya chiefs wanted to wage war against the Bari. The Bari chief Doka was very worried about the tense situation. He even cried before Fr. Vinco while thinking about his wives and children. Fr. Vinco encouraged him that he would try his best to stop the war. Fr. Vinco sent three messengers with gifts to the chiefs in question to inform them that Fr. Angelo told them not to fight. He himself would come to visit them to discuss peace. In six days the messengers returned each with a large tusk. Eventually all chiefs agreed in welcoming Fr. Vinco’s intervention. The chief of Belinyan Doka was most pleased and the people of the village made a great feast in honour of Fr. Vinco. He describes his joy in this successful enterprise as follows:

I cannot do justice to the happiness I felt at this successful outcome, and I thanked God for having listened to my prayers and for having softened those bitter hearts.

As soon as the leading personalities of Belinyan heard the good news, they immediately ordered a great feast to be held to which all the people were invited, including myself. At the feast, I heard myself being described as “liberator” or “father” and my name was hailed all for having preserved them from such imminent danger without fighting or bloodshed.

Fr. Vinco continues: “From that time onwards, I was greatly esteemed throughout the whole country. Everything I did was well done and all prejudices against me were forgotten.”[44]

Fr. Vinco did not fear to speak about Christian faith. Once he discussed with Jubek, the Bari-rain-chief, about the riches of the chiefs in Africa. Jubek asked Fr. Vinco whether the “white chiefs” were as rich as the African ones. He answered that they were far richer. Jubek asked him how many wives they had. Fr. Vinco answered they had only one wife. Jubek laughed. Fr. Vinco then explained God’s 10 commandments and the promise of eternal life.[45]

The conditions in which Fr. Vinco and the other missionaries found themselves were not always easy. They had to depend on the food that their hosts could afford giving them. During the times of famine and draught things became even more complicated and hard. Fr. Vinco reports:

I had already gone part of the way, when I came across some young women drawing water from a well. As I was extremely thirsty, I approached them and, in their language asked them to give some to drink, in return for some beads. No sooner had I uttered these words than they stared at me, and hurriedly made off with their pots towards their huts. My companions and I shouted after them, but it was all in vain, and the only result of our shouting, was that we were thirstier than ever. Parched, I rested from time to time under the shade of trees on the way, and we continued the rest of the journey in this way.[46]

7. The fame of Fr. Angelo Vinco

Fr. Vinco himself speaks about the esteem the Bari started having of him. Before people could know the traders they were friendly to the missionaries:

I was beginning to be held in higher esteem; they spoke well of me on all occasions, treated me with greater respect and consulted me in their public and private affairs. They went so far as to call me Juok, the name of one of their gods[47]

As seen above, his friend the traveller and trader A. Brun-Rollet reports that Fr. Vinco was given a royal Bari funeral. Over “3000 to 4000 came wail at his tomb and eight days of morning were observed.”[48] Songs were composed by people to evoke the life of Fr. Angelo Vinco among them. “His reputation was so great that he was remembered in Equatoria even a century after his visit,”[49]

In 1851 Cardinal William Massaja, who first criticized Vinco and the Austrian mission among the Bari, later compared him to a second St. Francis Xavier.[50] Both assessments might sound somehow exaggerated, yet they give an idea of the missionary stature of Fr. Angelo Vinco.[51]

The American diplomat and traveller, Bayard Talor, in Life and Landscapes in 1854 wrote about the missionaries Knoblecher and Vinco and others as follows:

Those self-sacrificing men have willingly devoted themselves to a life - if life it can be called, for it is little better than a living death - in the remotest heart of Africa. [...] They are men of the purest character and animated by the best intentions. Abuna Suleiman, as Dr Knoblecher is called, is already widely known and esteemed throughout the Sudan.[52]

James Hamilton in Sinai, the Hedjas and Soudan wrote in 1857 concerning Frs. Knoblecher and Vinco:

Both among Turks and Arabs, Abuna Suleiman, as Dr. Knoblecher is called, enjoys the highest consideration; far and wide I heard him spoken of with respect. [...] This is already a great success [...] for it helps the breaking down of colour and religious prejudice. [...] Those who have been long enough in the country to be known, have left a memory venerated by all, even by the pagans, and the funeral chant of one who died last year at his Station up the river, Don A Vinco, a gentleman of Verona, is still sung in their assemblies, as it was composed by the Africans themselves.[53]

In 1860 the French Consul Guilaum Lejean wrote the following assessment of Vinco:

Angelo Vinco was the perfect type of the Christian missionary in the Sudan [...]. He was adventurous, brave, fun and an excellent shot; he was greatly admired by the Bari, whose language he spoke.[54]

In 1870 Comboni gives a report to Bishop Luigi Curcia, the Apostolic Delegate of Egypt, about the Apostolic Vicariate of Central Africa and mentions quite extensively the work of Fr. Vinco among the Bari in Gondokoro. Comboni considered Fr. Vinco a man of God, burning with “divine charity” inside, a motivated missionary, who studied the local language, who tried to explore and get acquainted with the geography of the land and the customs of the people. He even explored the territory in view of discovering the sources of the Nile. He was the first white person who had reached so far in the explorations of the sources of the Nile in his explorations. Comboni defines Fr. Vinco a “courageous missionary”.[55] He adds that he used to receive from the people “many gifts as a sign of extraordinary veneration. His name was famous among the Africans”.[56]

8. The closure of Gondokoro

The two priests, who survived Fr. Vinco in Gondokoro died soon after in early 1854. The only survival, Fr. Bartolomew Mozgan, in the same year 1854 moved away from Gondokoro and found Holy Cross (Chambe) among the Dinka, where he died just before the four of Mazza missionaries, among whom the young Comboni, arrived in 1858. In 1855 the Pro-vicar Fr. Knoblecher came to Gondokoro with a priest and brother to reopen the mission station. On this occasion he baptized eight boys and eight girls. One of them was Francis Xavier Logwit, who was taken to Europe (Brixen) by Fr. Franz Morlang. The young man helped to produce a Bari grammar.[57]

Fr. Mozgan gives the following picture of the situation of Gondokoro when he left for Holy Cross: “The Bari do not know how to distinguish between our house and the traders establishment.” All foreigners became intruders and were dangerous. All had learned to trade with the Bari using beads, as it was the custom of the missionaries, who wanted to gain the benevolence of people. The mission had bought land at Gondokoro. The Bari were never satisfied with the payment of the land. They were asking money for the stones used in building and the gardens planted. The people asked food in time of famine from the limited stock of the community. Being unmarried, the people thought that the missionaries were eunuchs and thus sorcerers or witches. Children were forbidden to remain with them less they would be bewitched. They became so isolated that they could not leave the mission. “The free days and free ways of Fr. Angelo Vinco had disappeared from the Bari country.”[58] Indeed the situation and the mood of people had changed since the time when Fr. Pedemonte during the first exploratory journey among the Bari wrote that they are “more sociable than the preceding tribes [...]. Their character is happy and care-free.”[59] They are “the most courteous of all the native people living the rivers banks.”[60]

Gondokoro was definitively closed in 1862, when the last missionaries Fr. Giovanni Beltrame and Fr. Franz Morlang left without the knowledge of the people.[61] Various attempts of reopening it were made by Comboni in 1877-1878. Comboni did not succeed, because he was in great debts, due to the fact that a British merchant, with whom Comboni had left mission money, went bankrupt. Comboni had also to feed people during a two year calamity.[62] The resources left were very few to start a new undertaking. Later Bishop Roveggio in 1902 also intended to reopen Gondokoro, but it was not possible, for he was discouraged by the British administration due to insecurity. On his way back Roveggio got sick and died at Berber.[63] It was eventually reopened by Bishop Geyer in 1912, and then finally moved in 1919 to the healthier place of Rejaf.[64]

Conclusions

This brief historical overview helps us to draw important considerations which have relevance also for our commitment to evangelization or new evangelization:

Fr. Vinco had great human and spiritual qualities. He was interested in geographical explorations. He wanted to discover the sources of the Nile. In his explorations he reaching beyond Nimule, before Speke and Gran discovered the lake Nyanza in 1862, precisely the year of the closure of Gondokoro. But especially he was a man of faith. He preached the Word of God and translated its spiritual implications into social and cultural concerns about peace and integral development of people. He was effective in his reconciling and pacifying activities among the various tribes in Central Equatoria.

Fr. Vinco was able to establish good interactions with people. He was deeply convinced that friendly relationships with people are an essential prerequisite for evangelization to be successful. Fr. Vinco was kind, generous, open to, and friendly with, the people, a courageous man not easily intimidated. With wise and respectful manners he promoted dialogue and friendly contacts with them.

Fr. Vinco was thus able to show in practice that there was great a difference between the business men, the slave traders and the missionaries. He was not afraid to present the Christian message in its challenging provocation to the Bari culture. People felt that he was a man of God, thus gaining their confidence and trust. The people who listened to him respected him because he knew how to be convincing, though they could not accept immediately the challenging message of Christ. Fr. Vinco had a great impact on the Bari population, who welcomed, appreciated and loved him. They remembered him up to 100 years after his death. Songs about him were sung for long.

Comboni found inspiration for his missionary vocation for Central Africa in Fr. Angelo Vinco. When Fr. Vinco went to Verona and communicated his experience to the 500 students of Mazza Institute, he had a great impact, especially because he was communicating “divine charity”. Comboni was deeply touched by the love of Christ irradiating from Fr. Vinco’s words and decided to dedicate himself entirely to the African mission.

Comboni took up the spirit of Vinco in his missionary endeavours. He wanted to reopen Gondokoro around 1870s, but circumstance did not allow him. Ideally, on the footsteps of Vinco, who was interested in the sources of the Nile, Comboni continued Vinco’s project in apostolic terms: he wanted to expand his work of evangelization from the present South Sudan up to the areas of the Great Lakes in Uganda. Particular events, quite painful for Comboni, did not allow him to fulfil his dream.

Fr. Guido Oliana

[1] Just to show the lasting importance of Fr. Angelo Vinco, I would like to mention two recent works. The most recent one was published by the University of Nairobi Press in 2007: Bureng G.V. Nyombe, Some Aspects of Bari History. A Comparative Linguistic and Oral Tradition Reconstruction. The author dedicates a few pages to the historical context of the missionaries among the Bari and in particular of Fr. Vinco. Another work was published in 1992 by E.J. Brill in Leiden. It is a doctoral dissertation presented to Amsterdam University by Simon Simonse, Kings of Disaster. Dualism, Centralism and the Scapegoat King in Southern Sudan (Studies in Human Society no 5), Leiden, E.J. Brill, 1992. The author dedicates chapter IV to the situation of Gondokoro and Bariland at the time of Fr. Vinco and highlights the outstanding figure of Vinco himself. The title of the chapter is: The passing of the glamour: the Bari (80-98).

[2] For a good historical introduction about the places, times and people involved in the African mission dealt with in this article, cf. E. Toniolo - R. Hill (edd.), The Opening of the Nile Basin. Writings by the Members of the Catholic Mission to Central Africa on the Geography and Ethnography of the Sudan 1842-1881, London: C. Hurst & Company 1974. For basic information about the biography of Fr. Angelo Vinco and relative sources and map about his explorations, cf. http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angelo_Vinco. See also R. Werner –W. Aderson – A. Wheeler, Days of Devastation. Day of Contentment. The History of the Sudanese Church Across 2000 Years, Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa 2000, 2nd rep. 2006.

[3] It included the whole Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, the part of Egypt south of Assuan, the French territory from Fezzan to 10° N. lat., parts of Adamaua and Sokoto on Lake Tchad, and the Nile Province of Uganda Protectorate. Catholic Encyclopedia: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14325a.htm

[4] E. Toniolo - R. Hill (edd.), The Opening of the Nile Basin, 2.

[5] I. Knoblecher, Journal of the Voyage on the White River-Central Africa, in E. Toniolo - R. Hill, The Opening of the Basin, 47-73; E. Pedemonte, A Report on the Voyage of 1849-1850, in Ib., 55-73.

[6] Angelo Vinco. First Christian to Live Among the Bari. His Journeys, 1851-1852, in E. Toniolo - R. Hill, The Opening of the Basin, 74-105.

[7] D. Comboni, Writings, n. 2044. Writings refers to the publication: The Writings of St. Daniel Comboni. Correspondence and Reports (1950-1881) of the Founder of the Comboni Missionaries. Preface by Cardinal Caro Maria Martini, London: Comboni Missionaries 2005; trans. from orig. Daniel. Comboni, Gli Scritti, Roma: Missionari Comboniani 1991.

[8] D. Comboni, Writings, n. 4797.

[9] E. Pedemonte, A Report on the Voyage of 1849-1850, 61.

[10] E. Pedemonte, A Report on the Voyage of 1849-1850, 66.

[11] Cf. E. Pedemonte, A Report on the Voyage of 1849-1850, 66-67.

[12] Cf. E. Pedemonte, A Report on the Voyage of 1849-1850, 66-67.

[13] I. Knoblecher, Journal of the Voyage on the White River-Central Africa, 53.

[14] E. Pedemonte, A Report on the Voyage of 1849-1850, 72.

[15] Angelo Vinco, 78.

[16] I. Knoblecher, Journal of the Voyage on the White River-Central Africa, 54.

[17] E. Pedemonte, A Report on the Voyage of 1849-1850, 69.

[18] I. Knoblecher, Journal of the Voyage on the White River-Central Africa, 53.

[19] E. Pedemonte, A Report on the Voyage of 1849-1850, 72.

[20] Cf. Bureng G.V. Nyombe, Some Aspects of Bari History, 108-109.

[21] D. Comboni, Writings, n. 2062.

[22] D. Comboni, Writings, n. 2063.

[23] Cf. D. Comboni, Writings, n. 6277.

[24] Cf. D. Comboni, Writings. n. 6278.

[25] S. Simonse, Kings of Disaster, 91.

[26] Cf. map of Vinco’s exploration in http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angelo_Vinco.

[27] Angelo Vinco, 94.

[28] Angelo Vinco, 95.

[29] Cf. Archivio della Sacra Congregazione di Propaganda Fide vol 5, fol.9/VIII/1852.

[30] Cf. D. Comboni, Writings. n. 6278.

[31] F. Werne, Expedition zur Entdeckung der Quellen des Weissen Nil (1840-1841). Mit einem Vorworte von Carl Ritter. Mit einer Karte und einer Tafel Abbildungen, Berlin 1948, 283-299; En. tr. Charles William O'Reilly, Expedition to discover the sources of the White Nile in the Years 1840, 1841, London: R. Bentley 1849, quoted in Bureng G.V. Nyombe, Some Aspects of Bari History, 108.

[32] Brun-Rollet, Le Nil Blanc en Sudan. Études sur Afrique Central. Moures et Coutumes des Sauvages, Paris: Librairie L. Maison 1855, 203, quoted in Bureng G.V. Nyombe, Some Aspects of Bari History, 109.

[33] S. Simonse, Kings of Disaster, 91.

[34] Angelo Vinco, 76.

[35] Angelo Vinco, 77.

[36] Angelo Vinco, 79.

[37] Cf. Angelo Vinco, 79.

[38] Angelo Vinco, 79-80.

[39] Angelo Vinco, 80.

[40] Angelo Vinco, 81.

[41] Angelo Vinco, 82.

[42] Cf. R. Werber - W. Anderson - A. Wheller, Day of Devastation, 142.

[43]Angelo Vinco, 82-83.

[44] Angelo Vinco, 84; cf. R. Werber - W. Anderson - A. Wheller, Day of Devastation, 143.

[45] Angelo Vinco, 93; cf. R. Werber - W. Anderson - A. Wheller, Day of Devastation, 143

[46] Angelo Vinco, 81.

[47] Angelo Vinco, 82.

[48] A. Brun-Rollet, Le Nil Blanc en Sudan. Etudes sur Afrique Central. Moures et Coutumes des Sauvages, Paris: Librairie L. Maison 1855, 203; quoted in Bureng G.V. Nyombe, Some Aspects of Bari History, 109.

[49] Cf. R. Werber - W. Anderson - A. Wheller, Day of Devastation, 142-143.

[50] Cf. Ministère des affaires étrangères, Paris, Correspondence commercial, Alexandrie, vol. 34, Massaia to consul-general A. L Moyene, 12 nov. 1851, referred to in E. Toniolo - R. hill, The Opening of the Basin, 7; cf. R. Werber - W. Anderson - A. Wheller, Day of Devastation, 143.

[51] Cf. R. Werber - W. Anderson - A. Wheller, Day of Devastation, 143.

[52] Quoted, in E. Toniolo - R. hill, The Opening of the Basin, 13.

[53] Quoted, in E. Toniolo - R. hill, The Opening of the Basin, 12.

[54] Quoted in E. Toniolo - R. hill, The Opening of the Basin, 7.

[55] Cf. D. Comboni, Writings, n. 2043.

[56] D. Comboni, Writings, n. 2063.

[57] Cf. R. Werber - W. Anderson - A. Wheller, Day of Devastation, 144.

[58] R. Werber - W. Anderson - A. Wheller, Day of Devastation, 145.

[59] E. Pedemonte, A Report on the Voyage of 1948-1950, 61.

[60] E. Pedemonte, A Report on the Voyage of 1948-1950, 66.

[61] Cf. D. Comboni, Writings, n. 762.

[62] Cf. R. Werber - W. Anderson - A. Wheller, Day of Devastation, 183.

[63] Cf. R. Werber - W. Anderson - A. Wheller, Day of Devastation, 217.

[64] Cf. R. Werber - W. Anderson - A. Wheller, Day of Devastation, 226.276.