Daniel Comboni

Missionários Combonianos

Área institucional

Outros links

Newsletter

In Pace Christi

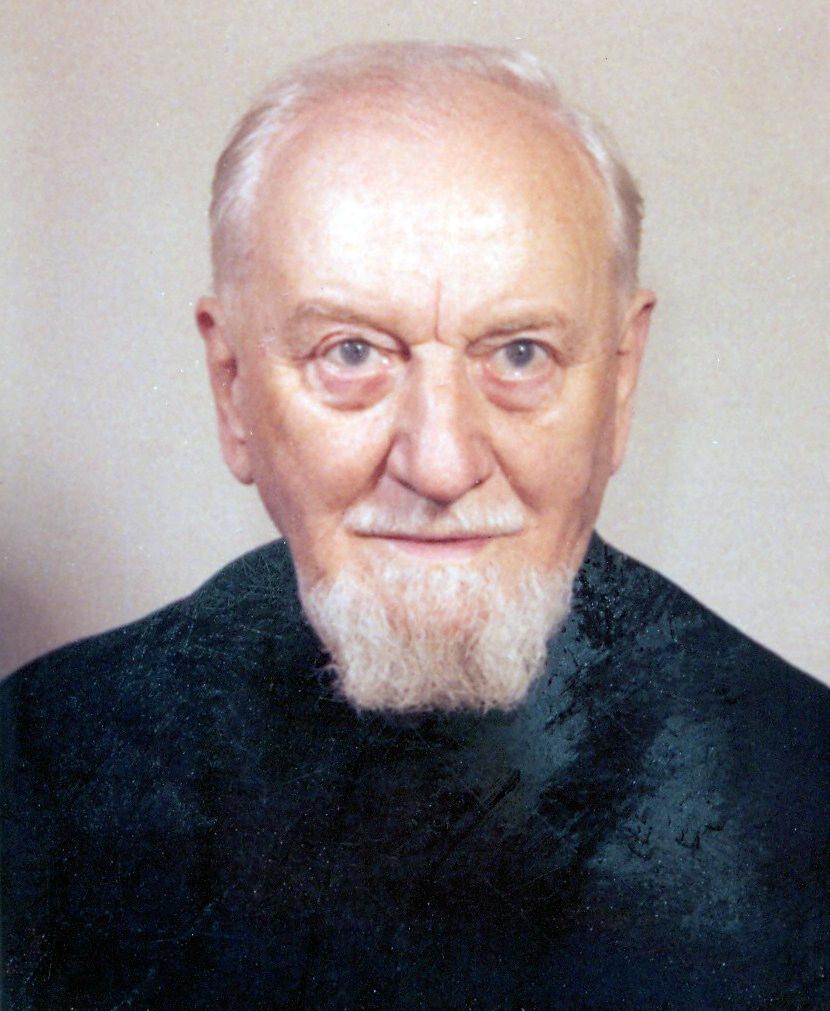

Sembiante Fernando

L'infanzia di P. Sembiante è avvolta da un velo di riservatezza quasi impenetrabile, sia perché l'interessato non amava parlare dei suoi anni giovanili e della sua famiglia, sia perché, essendo passato alla Casa del Padre in età considerevole, non ha lasciato testimoni che ci parlassero di lui.

In una lettera scritta al segretario provinciale, P. Sembianti afferma che i suoi antenati, molto probabilmente, discendevano da una nobile "gens romana" emigrata in Bretagna al tempo delle conquiste romane. Bisogna onestamente riconoscere che qualche cosa di nobile c'era davvero nel suo modo di fare.

I suoi genitori, Natale Sembiante e Rosa de Zotis, erano buoni cristiani, a meno che non sia stato il figlio seminarista a renderli tali, dopo la sua entrata in seminario.

La vocazione

Altrettanto misteriosa è l'origine della vocazione di P. Sembiante. La cugina ultrasettantenne, l'unica parente che siamo riusciti a rintracciare, ci racconta un episodio che P. Fernando stesso le avrebbe narrato tanti anni fa.

Da bambino stava giocando con le biglie sul sagrato della chiesa insieme ad altri compagni. Quella mattina la fortuna continuava a baciarlo in fronte per cui il piccolo Fernando vinceva e vinceva fino a trovarsi con tutte e due le tasche talmente piene di biglie da strapparsi. In quel momento passò il parroco. Fernando gli disse: "Ho vinto tutto!". E il parroco: "Cosa vale vincere anche tutto il mondo se poi perdi l'anima?". Quelle parole fecero un effetto tremendo sull'animo sensibile del piccolo che si domandava con una certa angoscia se quella spudorata vittoria non fosse segno di una sicura dannazione eterna. E, come San Francesco, si spogliò delle biglie regalandole ai compagni. Non solo, ma da quel giorno si sforzò di diventare ancora più buono, più gentile... Il Signore premiò la sua generosità facendogli sentire il desiderio di diventare sacerdote.

Non abbiamo nessun documento sulle reazioni della famiglia alla sua decisione. Sappiamo con certezza - nell'archivio di Brescia ci sono i registri - che Fernando Sembiante entrò nell'Istituto Comboni di Viale Venezia nel 1913 per gli esami di ammissione alle medie (che allora si chiamava ginnasio) e fu promosso con tutti dieci. Sappiamo che dal 1914 al 1919 compì gli studi ginnasiali presso l'Istituto Arici di Brescia, allora tenuto dai Gesuiti, sempre con voti brillantissimi, tanto che il ragazzino poté dedicarsi alla musica e alla poesia, sviluppando in queste arti un talento che possedeva da madre natura. Suoi compagni di scuola, anche se in anni diversi, furono: P. Uberto Vitti, P. Cesare Gambaretto e... papa Paolo VI.

Formazione religiosa

Fernando entrò in noviziato a Savona nel 1919. Aveva 17 anni. Il noviziato, da Verona, era stato trasportato in quella cittadina lontana dal fronte e quindi dai pericoli.

Anche a Savona il noviziato non ebbe vita facile e dovette cambiare residenza per ben tre volte: nel settembre 1916 a Villa Rosa, nel 1919, proprio quando entrò Fernando, in una parte del seminario vescovile, e nel 1920 in un vecchio convento, allora villa del seminario, chiamata "Loreto". Tra i compagni di noviziato c'era Fr. Giosuè dei Cas, reduce da un'esperienza africana di 14 anni come laico.

Il fervore era di casa in quell'ambiente. E anche Fernando cercò di non essere da meno degli altri.

Nel 1921 i Comboniani acquistarono il castello di Venegono e vi trasportarono il noviziato. Anche Sembiante cooperò al trasloco e lì emise la professione temporanea il 1 novembre 1921.

Quindi passò a Verona per la teologia e venne ordinato sacerdote nella città scaligera l'11 luglio 1926 dopo aver ottenuto da Roma la dispensa di cinque mesi per l'età prescritta per l'ordinazione sacerdotale.

Ecco come P. Fernando descrive se stesso (senza dire, naturalmente, che parlava di sé): "Alto, biondo, una grande fronte ampia, piena di pensiero, e due occhi celesti, bellissimi, che sprizzavano intelligenza e bontà e sembravano leggere nelle anime. Gli studi erano stati splendidi, senz'apparente fatica, senza esaurimenti, senza complessi. Ecco questi erano i dati di fatto. Ma era anche un fatto il fascino ch'emanava dalla sua persona, sebbene cercasse di minimizzarlo. La gente diceva ch'era come il fascino che aveva dovuto avere la persona del Signore, una specie d'incanto di purezza, che ammaliava soprattutto i giovani".

In Uganda, con quelli della prima ora

Dopo qualche mese a Verona come addetto al ministero, P. Fernando partì per l'Africa, con destinazione Arua. Era il gennaio del 1927: aveva appena 25 anni.

La documentazione delle sue avventure africane è così abbondante, che si potrebbe scrivere comodamente un libro. Fu un assiduo e apprezzato corrispondente di "La Nigrizia" sulle cui pagine registrava gli avvenimenti di missione.

Il suo destino fu quasi sempre quello di insegnante. Perché insegnante? Perché era bravo e perché aveva il dono di mettere nella testa dei suoi scolari le verità che andava via via spiegando.

Quindi dal gennaio del 1927 al dicembre del 1932 insegnò nel seminario di Arua. Ne divenne anche rettore.

Lui stesso descrisse le difficoltà iniziali: povertà, strutture inadeguate, solo quattro candidati. Pare che una suora abbia offerto la propria vita per quest’opera: di fatto si ammalò e in breve tempo morì. Il seminario si sviluppò in un modo che aveva del prodigioso. Vocazioni, personale scelto, riconoscimento da Roma, trasferimento in nuove sedi grandiose, dove diventò filosofico, teologico, e diede alla Chiesa e al mondo sacerdoti, vescovi, martiri.

P. Sembiante non si limitò solo all’ufficio di professore! Amava il ministero, amava le anime. E allora eccolo fuori, nei villaggi, in cerca dei più poveri, dei vecchi, dei malati, specialmente dei lebbrosi per i quali aveva una predilezione tutta particolare.

Chi scrive, quando rappresentava l'Istituto presso l'Associazione Amici dei Lebbrosi di Bologna, fu avvicinato da P. Sembiante il quale gli chiese se fosse possibile per lui, ormai ottantenne, frequentare un corso di leprologia per dare un aspetto più incisivo al suo ministero sacerdotale tra questi sfortunati. E di lebbra se ne intendeva perché aveva studiato per conto proprio la malattia e tutte le sue complicanze. La sua proposta fece esclamare ai responsabili dell'Associazione: "Che razza di missionari avete, voi Comboniani!".

Dai malati di lebbra P. Sembiante apprese grandi lezioni di vita come quella offertagli da una giovane donna, sana, che per anni curò e assisté il marito lebbroso: "Padre, io sono cristiana e ho ricevuto il sacramento del matrimonio, quindi devo stare con mio marito anche se malato".

"Aiutare chi soffre è un dono di Dio ch'Egli non dà a tutti. Certe anime non ne sono degne, e con queste il Signore non vuole avere nessuna obbligazione".

Per i poveri e i bisognosi P. Sembiante non esitava a svuotare la dispensa della missione mettendo nei pasticci i confratelli. Dava via senza pensarci due volte anche la sua biancheria personale.

Nel 1932 P. Sembiante venne in Italia, per curare la salute seriamente compromessa durante i duri anni d'Uganda. Ma ancora una volta dovette fare l'insegnante, prima a Venegono (1933-1934), quindi a Troia (1934-1935).

Aveva grande stima della vocazione missionaria e si adoperava come meglio poteva per animare missionariamente le persone.

Seconda fase africana: in Sudan

Nell'ottobre del 1935 P. Sembiante era a Khartum, Collegio Comboni, come insegnante. Vi rimase fino al 1942. Dal 1942 al 1947 fu ancora insegnante nel seminario di Okaru.

Nel 1947, alla fine della seconda guerra, tornò a Verona per dedicarsi al ministero, fino al 1949. Seguirono due anni in Inghilterra (1949-1951) per lo studio dell'inglese e come addetto al ministero.

"Bastarono due anni scarsi nella grande metropoli straniera - scrive - e il suo ministero assunse proporzioni sempre più vaste e profonde. Tutti volevano che rimanesse con loro, persone del clero, della cultura, del popolo. Un plebiscito di stima, di venerazione, di affetto. E molti dicevano: 'Ma perché questo Padre non rimane con noi?. Lo si sciupa in Africa. Ne abbiamo tanto bisogno anche qui'".

Il cuore di P. Sembiante, però, è sempre stato in Africa e per l'Africa. Davvero come Comboni poteva dire: "Se avessi cento vite, tutte le darei per l'infelice Nigrizia".

Nel 1951, dunque, eccolo di nuovo in Sudan. "Zanzare, zanzare, zanzare, e tafani, e mosche, e insetti, e febbri, e serpenti, e belve, e quella povera gente dalla vita così miserabile, gettata lì nella palude o nella savana, lontana, sparsa, in continua lotta omicida tra famiglia e famiglia, tra villaggio e villaggio".

Nel marzo del 1951 P. Sembiante era direttore della scuola tecnica di Torit. Vi rimase fino al 1956. Nei momenti liberi dalla scuola andava nel lebbrosario lontano cinque chilometri dalla missione per assistere i malati ai quali portava materassi, coperte, zanzariere, cibo, medicine... tutto quello che riusciva a farsi mandare dall'Europa o che trovava nelle missioni. "L'ho visto io - dice P. Danzi - quando baciava i lebbrosi, vivi e anche morti. Altro che scherzi!".

Ad un certo momento P. Sembiante credette di essere stato colpito dalla lebbra. In un suo libro narra questo momento di paura e poi canta la gioia di sapersi sano. Non per questo, però, diminuì la sua condivisione con i lebbrosi.

La rivolta di Torit

A questo punto dobbiamo inserire un avvenimento che mise in risalto la tempra di P. Sembiante e che gli ha guadagnato una benemerenza dal governo arabo di Khartum. Si tratta dei fatti che hanno dato inizio alla guerra del Sud contro il Nord, in Sudan.

"La sorda corrente sotterranea che da tempo rombava minacciosa nel Sudan meridionale, eruppe torbida e inarginabile pochi minuti prima delle 8, il mattino del 18 agosto 1955, nel cortile della Seconda Compagnia a Torit.

La Compagnia, formata da Neri, aveva avuto l'ordine di partire per Khartum. Mentre il primo plotone marciava verso il deposito delle armi, un mormorio indistinto si levò tra i soldati degli altri plotoni, mormorio che presto si fece tumulto. Ogni sforzo degli ufficiali arabi per dominare la situazione fu vano...".

I soldati africani si scagliarono contro gli ufficiali arabi trucidandoli, poi scaricarono la loro rabbia contro i civili arabi che erano numerosi in città e che avevano in mano il commercio. Fu una carneficina.

P. Sembiante si trovò in mezzo a quel macello... E scrisse (teniamo presente che si esprime come se fosse un altro, non lui): "Era cosa mirabile vedere quell'umile e insignificante sacerdote, splendidamente impavido, incurante d'ogni pericolo, l'occhio sempre triste, ma dolce e fermo fra tanto livore e tanta confusione, andare e venire inerme, di giorno e di notte, dovunque e quando pensasse che avesse diritto di trovarsi il suo Dio. Dinanzi a lui, e a quel suo sguardo, s'abbassavano i mitra e le lance più selvagge. E le palle, che spesso gli fischiarono intorno alla testa, non lo colpirono mai...".

Egli riuscì a convincere alcune decine di arabi a rifugiarsi nella missione, con le rispettive famiglie. Altri erano stati messi in prigione. Questi ultimi vennero tutti trucidati. Era il 20 agosto. Poi la ciurmaglia si diresse feroce verso la missione per sterminare anche gli altri. Prosegue P. Sembiante:

"Gl'infelici, che vedevano tutto dalle fessure, scoppiarono in un pianto generale, straziante. Il Padre si mise tranquillamente davanti alla porta: 'Sì, quelli che voi cercate sono qui; ma non potete entrare senza passar prima sul mio cadavere'. Trascorsero alcuni minuti di tensione suprema. Anche dentro non piangevano più. I soldati e i Lotùho, fermi, guardavano il missionario. 'V'è più facile ammazzare donne e bambini, che andar a combattere contro i loro uomini. Non vi vergognate?'.

A quella sferzata, qualcuno ribatté rabbiosamente, con parole mozze. Ma il loro capo disse piano tra i denti: 'Il Padre ha ragione'. E diede ordine che si lasciasse la missione".

Nel suo desiderio di pace, P. Sembiante convinse tanti neri a consegnare le armi. Gli arabi, avuto il sopravvento con l'aiuto degli inglesi, fecero giustizia sommaria di quei poveri africani e, questa volta, P. Sembiante non poté frapporre i suoi buoni uffici, cosicché passò come un traditore dei neri.

Dal 1956 al 1957 fu insegnante al seminario del Tore. E poi espulso perché "professore", cioè persona importante, che aveva influsso sulla gioventù sudanese. A nulla gli valse il certificato di benemerenza ricevuto dal governo di Khartum per aver salvato tanti arabi nei giorni terribili di Torit. Dovette andarsene.

Oltre oceano...

Dopo un anno in Italia come animatore (1957-1958), venne trasferito negli Stati Uniti: Cincinnati (1958-1959); Monroe (1959-1960), sempre come animatore.

In questo periodo allargò la cerchia degli amici delle missioni. Egli stesso se ne face tanti che lo aiutarono quando tornò in missione.

Ormai avanti con gli anni, avrebbe voluto andarli a trovare. Chiese il permesso al Superiore Generale, ma si sentì rispondere che la nuova politica dell’Istituto era contraria ai viaggi non strettamente necessari, quindi lui, anziano, doveva dare buon esempio ai giovani. Obbedì senza ribattere.

Rimase un anno a Verona (1960-1961) come addetto al ministero, quindi andò nuovamente in Africa. Dal 1961 al 1965 fu a War, in Uganda, come direttore del Collegio.

Nel 1965 rientrò in Italia e vi rimase fino al 1967 per rimettersi in salute e per le vacanze.

Missionario in Zaire

Dal 1967 al 1970 fu insegnante a Kilomines, in Zaire. Seguirono alcuni mesi di vacanze in Italia, quindi nuovamente in Zaire, a Rungu, come insegnante (1971-1975).

Ancora un salto in Italia e poi a Mungbere quindi a Rungu come insegnante nel seminario minore.

Qui il superò una tentazione come San Tommaso d'Aquino. Sentiamolo: "Era un bel pezzo d'uomo, con occhi azzurri, quell'ufficiale di Dio nei camminamenti dell'Africa equatoriale... Scura quella notte senza luna, e un temporale s'avvicina mugghiando da est. Il missionario entra nella sua camera e accende la luce. Fa per andare verso la scrivania, e udire come un lieve mugolio e sentire una giovane donna abbandonarsi tutta sulla sua persona fu una cosa sola.

Il Padre si staccò subito, dolce ma fermo, e la guardò sorpreso. Era una maestrina, una brava e bella ragazza, che si vedeva spesso in chiesa. E sempre molto elegante. 'Che succede, Teresa?'. L'altra fece per riavvicinarsi e poi: 'Se non acconsente, Padre, io comincerò a urlare, e verrà gente e l'accuserò'. 'Ah! È così?'! E il Padre che fino a quel momento aveva parlato in lingala e con voce sommessa, perdette le staffe e le rovesciò addosso un torrente rovinoso di schietto toscano alzando man mano sia il tono che la voce".

A questo punto seguono tredici parolacce (chi vuol leggerle vada a p. 45 di "In un'altra anagrafe).

"E l'ultima - prosegue P. Sembiante - fu un tuono, e aveva alzato il braccio aristocratico".

Chi scrive questo necrologio fu presente alla disputa tra P. Agostoni, allora Superiore Generale, e P. Sembiante sull'opportunità di pubblicare questi fatti. "Sarà vero, o è frutto della sua fantasia?", tagliò corto il Superiore Generale. "Verissimo, e fa, anche questo, parte della vita missionaria", rispose P. Sembiante. "Beh, allora lo pubblichi", concluse poco convinto P. Agostoni.

La devozione alla Madonna

La Madonna occupava gran parte del cuore di P. Fernando. Su questo le testimonianze dei confratelli sono unanimi. La sua morte, poi, ne è stata la prova suprema. Egli stesso ha affermato che è sempre riuscito a recitare tre rosari ogni giorno, e che alla Madonna affidava i suoi problemi e quelli delle persone che avvicinava.

Come Dante e Petrarca avevano la loro donna che ispirava la loro arte e dava un senso al loro comportamento, P. Sembiante aveva la Madonna alla quale ha dedicato moltissime poesie, per lo più rimaste inedite, e composizioni musicali che eseguiva al pianoforte. Insomma la Madonna era la sua "donna".

Il suo apostolato mariano si manifestava particolarmente con le ragazze. Non si tirava mai indietro quando c'era da parlare della Madre di Dio e indicarla come maestra e modello di ogni virtù.

In prossimità delle feste della Madonna teneva meditazioni e conferenze alle ragazze nell'intento di prepararle alla consacrazione al Cuore Immacolato di Maria. Tale consacrazione era sottolineata da un segno esterno: la consegna della medaglia miracolosa che il Padre - compito delicato e riservato esclusivamente a lui - appuntava personalmente sul cuore delle candidate. La cerimonia aveva luogo un paio di volte all'anno, in occasione delle feste dell'Immacolata e dell'Assunta, ed era celebrata con molta solennità e partecipazione di fedeli.

Seconda tappa in America

Dal 1979 al 1984 fu negli Stati Uniti, a Montclair come incaricato dell'animazione.

Era incredibile vedere un uomo ultraottantenne che si prestava sempre volentieri, anzi con entusiasmo, a predicare giornate missionarie.

La gente rimaneva edificata dal suo comportamento, dalla sua parola suadente, dalla testimonianza di una vita tutta offerta al Signore e alle anime senza badare a sacrifici e umiliazioni, dalla sua preghiera prolungata prima e dopo la santa messa.

La sua giornata cominciava prima delle cinque del mattino davanti al tabernacolo e terminava davanti al Signore prima di coricarsi.

Le sofferenze di P. Sembiante

L'estrema sensibilità di P. Sembiante e il modo piuttosto sbrigativo di certi confratelli gli furono causa di grandi sofferenze. Aveva l'impressione, e qualche volta la espresse nelle sue lettere, di non essere capito.

Poi ci fu il Concilio Vaticano II con le sue riforme. P. Sembiante ha sempre accettato ciò che la Chiesa proponeva in fatto di innovazioni, ma non sopportava le esagerazioni di certi confratelli che creavano la liturgia lì sul momento.

Non parliamo poi di un certo atteggiamento “borghese” vissuto da qualcuno. Ad un confratello che fumava come un turco disse: "Non pensa quanto cibo potrebbe dare ai poveri che muoiono di fame, con tutto quel fumo che manda in aria e che le nuoce alla salute?".

Ad un altro troppo pieno di se stesso scrisse argutamente: "Caro Padre, sei un portento di mente e santità; ma, com'è triste, sei un politeista, e non t'accorgi, ahimè, che adori Cristo e te".

Altra sofferenza: la sua produzione letteraria, sia in poesia che in prosa. Quanto alla poesia, tutti possono immaginare quanto quest'arte interessi i missionari rotti a ogni fatica e disagio e costretti a vivere in situazioni di prima linea. Rischiava, quindi, di passare per un sognatore che viveva con la testa tra le nuvole.

Una volta, mentre mostrava a chi scrive queste note una sua raccolta di poesie, delle quali i superiori avevano negato la pubblicazione giudicandola “cosa inutile”, disse: "Niente paura, in paradiso c'è una tipografia. Stamperemo là".

P. Sembiante scriveva non per uno sfogo personale, o comunque non solo per questo, ma anche perché, nello scrivere, vedeva un mezzo per fare del bene alle anime. E bisogna dire che, nonostante lo stile particolare, i suoi scritti erano apprezzati. Ho davanti agli occhi il libretto "Silenzi lontani" con la presentazione di Salvatore Quasimodo, premio Nobel per la letteratura.

Gli causava sofferenza anche il dover convivere, lui così sensibile e delicato, con confratelli dalla scorza piuttosto ruvida. Tuttavia fu sempre gentile e rispettoso, pronto ad accettare gli scherzi e i lazzi che gli venivano indirizzati.

Era anche molto generoso: regalò la sua motocicletta ad un confratello, mentre ad un altro regalò una macchina fotografica che aveva appena ricevuto in dono. Ciò dimostra anche il suo completo distacco dalle cose. Da un oggetto non si staccò mai fino alla morte: il vocabolario della lingua italiana. Gli piaceva parlare con proprietà e correttezza.

La sua mezz'ora di paradiso

Nel 1984 P. Sembiante venne definitivamente assegnato al Centro Malati di Verona, anche se poteva permettersi una certa attività ministeriale grazie alla salute, ancora discreta e, soprattutto, sostenuta da una volontà di ferro.

Celebrava la Messa da solo, prestissimo, quando in casa c'era ancora il massimo silenzio. Chiamava quel momento: "La mia mezz'ora di paradiso". E andava veramente in paradiso in quei momenti. Pur osservando rigorosamente le rubriche (teneva tanto alle rubriche, espressioni della voce di Dio!), effondeva il suo spirito fino alla commozione. Per questo preferiva celebrare da solo, senza testimoni umani. Tanto, sapeva che attorno al suo altare c'era tutto il mondo.

Poi, un po' alla volta, i suoi occhi celesti si spensero, le sue mani delicate, avvezze a volare sulla tastiera del pianoforte, brancolavano nel buio, e le sue orecchie, abituate alle melodie della musica e del bel canto, non sentivano più niente. Tutto aveva sacrificato al Signore in serenità di cuore.

In lui rimase fino all'ultimo quella nobiltà d’animo e quella gentilezza nel tratto che sempre lo distinsero. Sulle sue labbra fioriva continuamente la parola "grazie", accompagnando l'espressione con un inchino del capo. Anche con le addette alla pulizia del reparto si esprimeva con un "sì, signora, grazie"; o "no, signora, grazie". Insomma fu davvero un gentiluomo.

Abbiamo già parlato della sua devozione alla Madonna, tuttavia dobbiamo dire che, negli ultimi anni, la sua sensibilità nei riguardi della Madre di Dio e madre nostra si manifestava in modo superlativo. P. Sembiante era diventato il bambino fragile che aveva estremo bisogno della Mamma, e come tale si comportava.

Mille volte al giorno ripeteva: "Mamma Maria, portami via con te; Mamma Maria, portami via con te". E lo diceva con umile e fiduciosa insistenza. La sua morte, giunta del tutto inaspettata visto che, fino alla sera prima si sentiva come al solito, è avvenuta proprio nel giorno dell'Immacolata. E non può essere un fatto casuale, ma costituisce una precisa risposta di Mamma Maria a questo suo figlio, un po' poeta, un po' idealista, un po' sognatore, ma dal cuore limpido e fresco come una sorgente di montagna.

Anche il trapasso è stato particolarmente sereno come il dolce sonno dei patriarchi che si addormentavano nel Signore sazi di giorni e di meriti. L'infermiere, infatti, passando davanti alla sua stanza verso l'alba, udì un respiro un po' diverso dal solito. Entrò. Gli sembrava che dormisse. Invece stava esalando proprio l’ultimo respiro. E le campane di Verona cominciarono a suonare l'Avemaria. Era il mattino dell'Immacolata 1993.

Testimonianze

P. Danzi, per la messa di esequie, ha scelto le letture della Messa dell'Assunta, perché sarebbero state quelle che il Padre avrebbe preferito. Poi ha letto l'ultima poesia del Padre:

Mamma, non ci vedo più.

Deh! dammi la tua mano e portami,

conducimi al Signore.

E questo povero corpo mio

lascialo all'ultima carità

dei miei confratelli

per un funerale cristiano.

Poi P. Danzi ha continuato: "Ho passato tre anni con lui a Rungu; era lui che ci svegliava al mattino suonando l'Ave Maria con le tre campanelle; e, alla sera, quando spegnevamo il generatore e tutto si faceva buio, lui usciva nella veranda e con l'armonica a tastiera ci suonava l'Ave Maria di Schubert. Qualche volta noi sorridevamo, ma per lui era una cosa profonda, seria, segno di un grande amore.

Ora P. Fernando riposa nel cimitero di Verona insieme a tanti confratelli. E da lì continua ad irradiare entusiasmo missionario, idealismi santi ed esempi di bontà, lui che in molte sue lettere amava firmarsi: "Questo povero sembiante di Dio". P. Lorenzo Gaiga, mccj

Da Mccj Bulletin n. 183, luglio 1994, pp. 41-53

*****

The infancy of Fr. Sembiante is shrouded in almost impenetrable privacy, since the father never liked to talk about his childhood or of his family and also because he left for the house of the Father at such an advanced age that he outlives all those who might have told us something about him.

And yet in the many books he wrote, we can find many episodes of his life, since most of them are autobiographic, as those who lived with him testify, though the father, in his simplicity, never makes mention of himself.

Somebody tried, with discretion, to penetrate that mystery, and this is what he discovered: his family must have been of noble stock, dukes or princes or something like it, and came from Brittany, where they owned lands and castles as far back as 1000 A.D.

The French Revolution had wiped out all this family splendour, many lost their heads on the guillotine, while others first fled to Austria and then settled in Cadore. So he was of noble lineage!

In a letter written to the Provincial Secretary, Fr. Sembiante states that his ancestors probably came from a `gens romana', who had settled in Brittany at the time of the Roman conquests.

Whatever the exactness of this informations, we must certainly admit that his demeanour had an aura of nobility. His parents, Natale Sembiante and Rosa de Zotis, were very good practising Christians, unless their young son turned so devout only after his entrance into the seminary!

His vocation

Mysterious remains also the origin of the vocation of Fr. Sembiante. His cousin, a lady now over seventy and the only relative that we could trace, told us an episode that she had heard from Fr. Fernando himself.

He was one day playing, as a child, a child's billiard pocket game in front of the church with other of his little friends. That was a particularly lucky morning for Fernando, who kept winning and in the end his pockets were full of his winnings. Then the parish priest came to pass and Fernando told him proudely: "I have won everything!" And the parish priest remarked: "What is the use of winning even the whole world if you lose your soul?".

Those words sank into the child's mind with a tremendous impact, and he began to ask himself if by chance his winning streak was not a forewarning of his eternal damnation! Like St. Francis, he there and then gave back to his friends all his winnings and from that day he strived to be kinder, and better in all he did... The Lord awarded his generosity by giving him the wish to become a priest.

We have no record on how the family reacted to this wish of his. We know for certain - and it is recorded in the books of our Brescia seminary - that Fernando Sembiante entered the Istituto Comboni of Viale Venezia in Brescia in 1913, where he took the entrance exams for the secondary school and passed with top marks. We also have in the records that he did his secondaries at the Arici College, in Brescia, from 1914 to 1919. The Arici was then run by the Jesuits and our Fernando was ever so brilliant that he had plenty of time also for music and poetry, where he proved to be particularly gifted. His school mates were, though in different times: Fr. Vitti, Fr. Gambaretto and... the future Pople Paul VI.

Religious formation

Fernando entered the Novitiate, then at Savona, sometime in 1919. He was then 17 and the novitiate had been transferred to that riviera town from Verona, because it was far from the war front (the first world war).

The novitiate in Savona did not have an easy time, since it had to change see three times: Villa Rosa in 1916, in a part of the diocesan seminary in 1919, just when Fernando was entering, and from 1920 in an old convent, belonging to the seminary and called "Loreto". He had among his novice mates Bro. Giosué dei Cas, who had just returned from 14 years experience in Africa as a lay man.

The whole house was permeated with fervour and Fernando was just as fervourous as everybody else.

He showed a great wish of perfection and was always very careful and delicate about holy purity. He was subtle about his devotion and in general he is rather childish, living on phantasies and somewhat changeable, because he let himself be led by the heart and the imagination rather than by a sound and down to earth reasoning. He showed a very great sensitivity (a poet's characteristic!), but was also light hearted and unsystematic. He did his first year of Higher secondary school during his second year of novitiate".

In 1921 the Comboni Missionaries acquired the Venegono `castle' and the novitiate was once again transferred, this time from Savona to Venegono. Sembiante took part in the move and did his first religious profession in Venegono on the first of November 1921.

From there he went on to Verona for his theology and was ordained priest in that town on July 11, 1926, after getting from Rome a 5-months dispensation, because he was too young.

This is how the father describes himself (without saying that he is writing about himself, of course!): "Tall, fair hair, wide and thoughtful forehead, blue and very beautiful eyes, radiating intelligence and goodness, which seemed to reach out into the innermost of souls. He sailed through his studies effortlessly. This is what he was. But just as real was a kind of charm that issued from his person, though he tried not to give it importance. The people used to say that it was the kind of charm the the Lord himslef must have exerted, a kind of fascination which was the fruit of holy purity, that charmed particularly the youths".

In Uganda with those of the first hour

After spending a few months in Verona, Fernando left for Africa, assigned to Arua in Uganda. It was January 1927 and the father was only 25.

The records of the Father's African adventures are so long that we could easily write a book. He was a regular, and esteemed, contributor of "Nigrizia", recording mission events. More than striking adventures, Fr. Sembiante was fond of describing the small miracles that divine grace worked in the souls. He wrote down many of this facts.

We could mention here what happened to him once among the Logbara, when a strange character one day barred his way and he was forced to take another route to return to the mission. He later learnt that had he continued along the original route he would have been caught in a bloody revolt against the whites (British) where he could easily have been killed.

And again: once people from a far away village were led by a strange light to the village where the father was, in order to get the sacraments.

He worked side by side with Fr. Vignato, Fr. Valcavi and Fr. Sartori, to quote just a few. In the biographies of these great missionaries, we can see also the footprints of Fr. Sembiante.

But his main work was always as teacher. Why a teacher? Because he was good at it and he had the particular ability of making his pupils understand the truths that he was explaining.

From January 1927 to December 1932 he taught in the minor seminary of Arua and became also rector of that seminary.

He himself described the initial difficulties: poverty, unsuitable structures, only four candidates. A sister, it seems, offered up her life for the seminary, and in fact she fell sick and died within a short time.

The seminary developed in a wonderful way. The number of candidates kept increasing, the staff got better and better, Rome soon gave its approval and support, and within a short time it was transferred into larger and more dignified premises, with the addition of the philosophy and theology sections, giving finally to the Church and to the world priests, bishops, and martyrs.

Fr. Sembiante did not just stop at being a teacher! He enjoyed doing ministry among the people, in the villages, seeking out the elders, the sick, the lepers whom he loved with special affection.

The writer of these notes, when head of the Lepers' Friends Association of Bologna, remembers that Fr. Sembiante, then eighty, approached him and inquired if he could be admitted to a course for leprosy assistants in order to be more practical and effective in his approach to these unlucky brothers of ours. And he already knew a lot about leprosy, since he had studied the illness and all implications on his own. This request of his had those in charge of the Association exclaim: "What kind of missionaries have you, Combonians?"

From the lepers, Fr. Sembiante learnt many lessons of real life, like the one he got from the young healthy lady, who assisted her leprous husband for years. "Father, I am a Christian and I have received the sacrament of marriage, so I must be with my husband even if he is sick".

For the lepers he turned beggar with the European authorities in Africa, and even with kings, princes, actors and actresses. None of these ever replied to him, and the Father used to comment: "Perhaps the mere thought that those letters, coming from so far, were written by somebody who lived among the lepers, brr! must have given those ladies and lords cold shiverings; they must have thrown that paper into the fire immediately, as they rushed to disinfect their hands for having touched such a dirty thing!" He then added a bitter, but realistic, comment. "To help the suffering is a grace of God and He does not grant it to all. Some are not worthy to receive it and the Lord does not want to have anything to do with them".

Fr. Sembiante never hesitated to empty the mission storeroom to help the poor and the needy. He even handed out his personal linen.

He returned to Italy in 1932 because his health had suffered too much during those hard years in Uganda. Again he was sent as teacher first to Venegono (1933-1934) and the to Troia (1934-1935).

The father had also a great esteem for his missionary vocation, thus he endeavoured, as his health allowed, to spread the missionary idea and animate people.

Second stage in Africa: Sudan

In October 1935 Fr. Sembiante arrived at the Comboni College of Khartoum as teacher. He was there up to 1942 and then from 1942 to 1947 he taught at Okaru seminary.

In 1947, at the end of the second world war, he returned to Verona for ministry up to 1949. He was subsequently two years in England (1949-1951) to improve his English.

"Two years in London were engough for him to undertake - he himself writes in his usual impersonal style - a ministry that kept growing by the day. All were asking for him: the clergy, university lecturers and highly educated people, common people. He was really liked, respected and venerated. Many were saying: `Why can't this father stay here with us? To send him to Africa is a waste. We need him here!'". But the heart of Sembiante was in Africa and like Comboni he could say: "If I had a hundred lives, I would give all of them for Africa".

So in 1951 he was back in Africa.

"Mosquitoes, mosquitoes, mosquitoes, and flies, and insects, and fevers, and snakes, and wild beasts, and those poor people leading such a miserable life, in swamps or savannah, far away, scattered widely, fighting each other, feuding among themselves and between village and village".

In March 1951 he was appointed director of the Torit Technical school. He was there up to 1956. During his free time he would cycle to the leprosy center five kilometres from the mission to assist the sick with mattresses, blankets, mosquito netting, food, medicines... all that the good people were sending him from Europe or that he could find in the mission. "I saw him kissing the lepers, living and also dead. Not an easy thing!".

At a certain moment Fr. Sembiante thought that he had caught the disease. In one of his books he recounts this moment of fear and then sings his joy for being found healthy instead. But this did not stop him from keeping up with his attentions and predilection for the lepers.

The rebellion of Torit

Now we must speak of an event that showed the courage and stamina of Fr. Sembiante and won him the praises of the Arab Government of Khartoum. It was about the start of the rebellion that led to the war of the South against the North, in Sudan.

"The creeping underground current, a threatening current that for a long time had been stirring up matters against the Northern Sudan, burst out suddenly in the open on the morning of August 18th 1955, only a few minutes after eight o'clock in the yard of the 2nd Company of Torit.

The Company, composed all of Southern Sudanese, had received the order to transfer to Khartoum. As the first platoon was moving towards the armory, the other soldiers began making noises, that soon turned in open rebellion, and there was nothing that the Arab officers could do to control it...".

The African soldiers attacked their Arab officers and killed them and then began attacking the Arab civilians, mostly traders, who were quite numerous in town. It was a massacre. Fr. Sembiante found himself into that butchery... He wrote (remember that he always writes if it were about somebody else, not himself): "What a wonderful sight was this humble and insignificant priest, so courageous, not scared by the danger, sad eyed, but gentle and strong amidst so much hate and confusion, coming and going, day and night, wherever he thought somebody had the right to be with his God. The machine guns or automatic rifles or spears were lowered in front of him, and the bullets, though wistling into his ears, never struck him...".

He convinced some Arabs to take refuge in the mission with their families. Others instead were put in prison. These last were all killed on August 20th and after the massacre the enraged crowds converged on the mission to kill also the others. "The unhappy refugees - goes on the father - who saw what was coming, began to weep and wail. But the father stood in front of the door and told the crowd: `Yes, those that your seeking are here with me, but you will enter only passing over my dead body'. There followed a few tense minutes. Even the cries inside the house stopped. The soldiers and the Lotuho looked straight at the missionary. `You find it easy to kill women and children rather than fight their men. Aren't you ashamed?' The remark hit deep inside them and some wanted to reack furiously, but their leader finally admitted: `The father is right' and ordered his men to retreat and leave the mission".

In his wish for peace the father convinced many negroes to hand in their arms. The Arabs, once the rebellion was mput down with the help of the British, summarily executed many of those Africans and this time there was nothing that Fr. Sembiante could do to save them, thus he was accused by the Africans of being a traitor.

In 1956 and 1957 the father taught at Tore and then he was expelled, because he was "a professor", that is an important person who influenced the Sudanese youth. The praises he had previously received from the Khartoum Government for saving the many Arabs of Torit were useless. He had to leave.

Beyond the Atlantic...

After a year spent in Italy as mission animator (1956-1958), he was sent to the United States where he was at Cincinnati (1958-1959) and Monroe (1959-1960), always as mission animator.

During this period he increased the number of the friends of the missions. He himself gained many personal friends that continued helping him also when he returned to the mission.

Already on in years, he would have liked to visit them once again. He asked the permission of the Superior General, but he was told that the new policy of the Institute was against uneccessary travelling, and he, an elder was to give good example to the younger generations. He obeyed.

He was one more year in Verona (1960-1961 and then was re-assigned to Africa.

Uganda once again

From 1961 to 1965 he was at War, Arua, in charge of the college there. It was during this time that he made a memorable walk to bring the sacraments to a dying person. When after walking for hours he asked a young the way to that "village", and the youth offered to accompany him there. They finally reached the village... "One more turn and we shall be in the village. When thy saw the father, many came to greet him. `I have come to see Vito. How does he do? Where is he?'

`I am Vito' said the youth that had been accompanying him.

`But they wrote to me that you were very sick and dying'. `Oh, yes, but that was last week, and they had even began to dig my grave. But the good Lord has helped me and now I am healed'. This too is mission, concludes the father".

He returned to Italy from 1965 to 1967 for health reasons and for holidays.

Missionary in Zaire

From 1967 to 1970 he taught a Kilomines in Zaire. After a few months in Italy, he returned to Zaire, at Rungu, always as teacher (1971-1975).

After one more short stay in Italy he was at Mungbere, then at Rungu again as teacher in the minor seminary there. Here the father overcame a temptation like St. Thomas Aquinas. Let us hear how he describes it.

"He was a handsome person, with blue eyes, that officer of God on the roads of equatorial Africa... It was a dark, moonless night and a tropical storm was brewing up from the East. The missionary entered his room and switched on the light. As he was about to move to his writing desk, he hears a kind of low moaning and before he realized it a young lady was all over him in a warm embrace. The father broke free, kindly but firmly and then looked at her in surprise. She was a teacher, a beautiful girl often seen in church, and ever very elegant.

`What's the matter, Teresa?'

She made to approach and then said:

`Father, if you do not yield, I will start yelling, people will come and I will accuse you!'

`Is that so?' The father who had so far spoken quietly and in Lingala, lost control and began showering on her a stream of Italian words, raising the hand as well as the tone of the voice".

Here we have 13 rather nasty terms (you can read them at p.45 of "In un altra anagrafe").

"And the last - concludes the father - was a thunder as his raised his aristocratic arm".

The writer of these notes was present when Fr. Sembiante and Fr. Agostoni, then Superior General, discussed if it would be good to publish this fact.

"Is it true, or did you dream the whole thing?" cut in the Superior General.

"Quite true, and this is also part of my missionary life" replied the father.

"Well, then, go on and publish it" said Fr. Agostoni, who wasn't quite beleiving him.

But the dangers in the mission were not just from beautiful church going girls, catechism teachers etc., but also from snakes.

"Sunday March 2nd. Rungu, Zaire. The missionary, as usual takes his place to hear confessions in the parish church at about six in the morning, when it was still rather dark.

The confessional is in a corner, near the photos of the four comboni missionaries killed during the Simba rebellion in 1964.

After a while the father sensed the presence of something near him, like a small bundle... but the bundle had like two fluorescent points!

The missionary bent down to see better, now that the light was increasing.

It was a viper, with typical dark patches on the back, the trinagular head ready to strike! And the father had been confessing for over a quarter of an hour so close to that thing under there!

After finishing the last penintent, and keeping his eyes on the snake, that remained curled up and still but alert at all his movements, he rose slowly slowly and went out, to return soon after with a big stick...". And that is how also that tricky affair ended!

His devotion to Our Lady

Our Lady filled the greatest part of Fr. Fernando's heart. All confreres are unanimous on this. His death only proved it even more.

He himself used to say that he always prayed three rosaries every day and that he constantly entrusted to Our Lady his problems and worries and the problems and worries of the people he approached.

Dante and Petrarca had their lady who inspired their art and lives, likewise Fr. Sembiante had Our Lady, and he dedicated to her many of his poems, most of them never published, and musical compositions that he himself played at the piano. Well, Our Lady was his inspiring lady.

His love for Our Lady was particularly effective and clear when he taught girls. He never drew back whenever he could speak of Our Lady and never stopped presenting her as the model of every virtue.

As a feast of Our Lady was getting near, he would be giving meditations and lectures to the girls to prepare them for the consecration to Her Immaculate Heart. This consecration would be visibly marked by handing them the miraculous medal that he himself would pin on the heart of the candidates to the consecration. This ceremony normally took place twice a year, at the Feasts of the Assumption and of the Immculate Conception, feasts that were celebrated with special solemnity.

A second time in America

From 1979 to 1984 he was once again in the United States, at Monclair, as mission animator.

It was incredible to see how this man, now over eighty, was ever so ready to preach with enthusiasm on the missions.

The people were highly edified by his behaviour, by his words, by his witness of a life all offered up to the Lord and for the souls without ever pulling back from self-denial and humiliations, and praying long before and after the mass.

His day normally began before five in the morning in front of the tabernacle, and he would also end the day in front of the tabernacle, before going to bed.

The sufferings of Fr. Sembiante

The father was extremely sensible, and the brusque manners of many of his confreres caused him untold suffering. He was under the impression, and in his letters at time he said it, that he was not understood.

Then came Vatican II with all its reforms. The father has always accepted what the Church has done in matters of reforms and innovations; what he could not bear was the way some confreres changed the liturgy at will and on the spur of the moment.

He was also hurt by a bourgeois style of living of some of his confreres. To a confrere who was also a hard smoker once he said: "Have you ever thought how much food could be bought for the hungry poor with the money you spend in smoking, a habit which ruins also your health?".

To another who was too self-confident, he argutely said: "My dear father, you have got an extraordinary mind and your are quite holy; but can't you see that you are a politheist, since, dear me, you are worshipping Christ and yourself!".

His literary compostions, both poems and narrative were another source of suffering for him. As for the poems, the missinaries weren't certainly much interested in it. Their hard work and front line situations left little time for poetry! So the father was always looked upon as a kind of dreamer who lived with his head up in the clouds.

He once showed me a collection of poems that the superiors had refused him permission to publish because, according to them, it was a uselss thing, and he commented: "Don't fear, father, there is certainly a printing press in Paradise. I will have it printed there".

Other books of his were stopped for the same reason. He used to insist quietly and kindly in oder to see his collections of poems or narrative published. Once that he was refused permission to publish something that he considered important he wrote the poem "In Paradise there is a printing press".

And yet he never asked anybody for money. His friends, a highly cultured lot, always helped him out for these publications.

How sad was he when once, an offering given to fund the publication of a small booklet of his was forfeited by the bursar, who didn't certainly show a poetic charism! He had to write to the Superior General to get the offering back, but in his letter he had written: "If you think it right, otherwise let things as they are".

He was not writing just to give vent to his feelins, or at least not just for this, but because he considered writing a way of helping people.

And we have to admit that, in spite of his particular style, his writings were well received. I have here in front of me the booklet "Silenzi lontani", with presented by Salvatore Quasimodo, a Nobel prize for literature.

Another source of suffering for him was to have to live with confreres who behaved rather rudely. He was ever so kind, respectful and gentle, and he was particularly hurt by the jokes or quips addressed to him.

He was ever very generous with his confreres: to one he gave his motorcycle, to another his camera he had just received as a gift. But one thing he never gave away: the Dictionary of the Italian language. He liked to talk always correctly.

His half-hour of paradise

In 1984 the father was assigned to the Medical centre of Verona, though he was still self-sufficient and could do some little ministry.

He used to say Mass alone, very early in the morning, when all was quiet around him. He had named that moment: "My half-hour of paradise". And during that half-hour he would really feel in paradise indeed. Though keeping all the rubrics (for him they were the expression of the will of God!), he used to pour out his spirit. This is also why he preferred to celebrate all alone, without anybody watching him. He was sure, however, that the whole world was round about his altar.

Little by little his blue eyes went out, his delicate hands, accustomed to fly on the keys of the piano, began to move in the dark, his ears that could pick out the beautiful melodies and songs, became deaf. He gave in to the Lord all in serenity and simplicity of heart.

Up to the last he kept that special nobility of spirit, that gentle behaviour that was his characteristic throughout. On his lips he always had the word "thank you", accompanying the sound with a bow of the head. And the lady who swept his room was always addressed by "Yes, thank you, madam, thank you" or "No, madam, thank you". He was a gentleman.

We have already mentioned his devotion to Our Lady, but we must add that, in his last years, this devotion towards the Mother of God reached very high peaks. Fr. Sembiante had become a fragile child, who was in extreme need of the Mother, and as such he behaved.

He kept repeating throughout the day, without ever tiring: "Mother Mary, take me away with you; Mother Mary, take me away with you". And he said it humbly and trusfully. His death was unexpected, because he had been well, or at least had not given any sign of worsening. He died on the day of the Immaculate Conception, and it wasn't certainly by chance: it was the wonderful reply of the Mother Mary to his child, partly poet, partly idealist, partly dreamer, but who had a limpid and fresh heart, like a mountain source.

He died quietly, as if falling asleep, like a patriarch who falls asleep in the Lord, full of days and of merits. In early morning the male nurse passing in front of his door noticed that the father was not breathing normally. He entered and the father seemed asleep, but was in fact entering into the sleep of the just. The bells of Verona were beginning to tall the Avemaria. It was the morning of December 9th 1993, the morning of the feast of the Immaculate Conception.

What confreres say of him

Fr. Cona who was with the father at the Medical centre for many years, calls him "Master. A blind Master who saw better than any of us who still have eyes, because he saw things with the eyes of the faith... He led all people to smile with his enthusiasm and love of Mary. When told that the mass was starting he would exclaim: `what a joy, what a joy!' and the same thing he repeated as he was receiving holy communion.

He was a simple man, ever so kind, amiable, gentle, ever ready wo say `thank you'. I never heard a complain from him. My room was next to his, only a wall separated us. At night I could hear him invoking the Mother Mary, and he kept praying to her also during the day, when others would be watching television. He was blind and deaf, but he was always with his community and in prayer.

How many are the things that one could say about him, but how can we say them all? Let me just add this: he taught us a lesson of love, sound, truthful, tender and simple for the two treasures God gave us: Jesus and Mary".

Fr. Danzi for the funeral mass chose the readings of the feast of the Assumption, because he knew that they were tho ones that the father would have liked. After the liturgy he read the last poem of the father:

Mother, I can't see any more

Please! Give me your hand

and lead me to the Lord.

Leave this poor body of mine

to the charity of my confreres

for a Christian funeral.

Fr. Danzi then continued: "I passed three years with him at Rungu; he was the one to wake us up, ringing the Avemaria with the three small church bells. In the evening, when also the generator was put off and all was dark, he would go out on the verandah and with the portable organ he would play the Ave Maria by Shubert. At times we would just smile, but for him it was a very serious thing, a great sign of love.

This was also his way of being missionary. He had identified Mary, mother of Jesus, with the mother of Africa, the mother of the life that was blooming all around him. He was the missionary with the rosary beads in his hands, and he handed out rosaries and the miraculous medals of Our Blessed Lady to all.

On Saturdays, at three, you could find him in church, always with the rosary beads in his hands, available for confessions. And he did the same on Sunday morning, before the rising of the sun.

He was taking care of the sick. If anybody died without receiving the sacraments, he would be all worried. What has he not done for the sick! He was very sensitive to the sufferings of others; everything had to be tried for the others, and he would not pull back, giving away even his bed sheets, his blankets, his shirts".

"In Rungu and surroundigs, you could be sure that any child born at the maternity centre or at the hospital had been baptized by Fr. Sembiante. He never wanted to hear of the Baptism record book. He used to say that Our Blessed Lady knew well her children and did not need a record book to keep a record of the!.

As soon as person died, he w