Daniele Comboni

Missionari Comboniani

Area istituzionale

Altri link

Newsletter

In Pace Christi

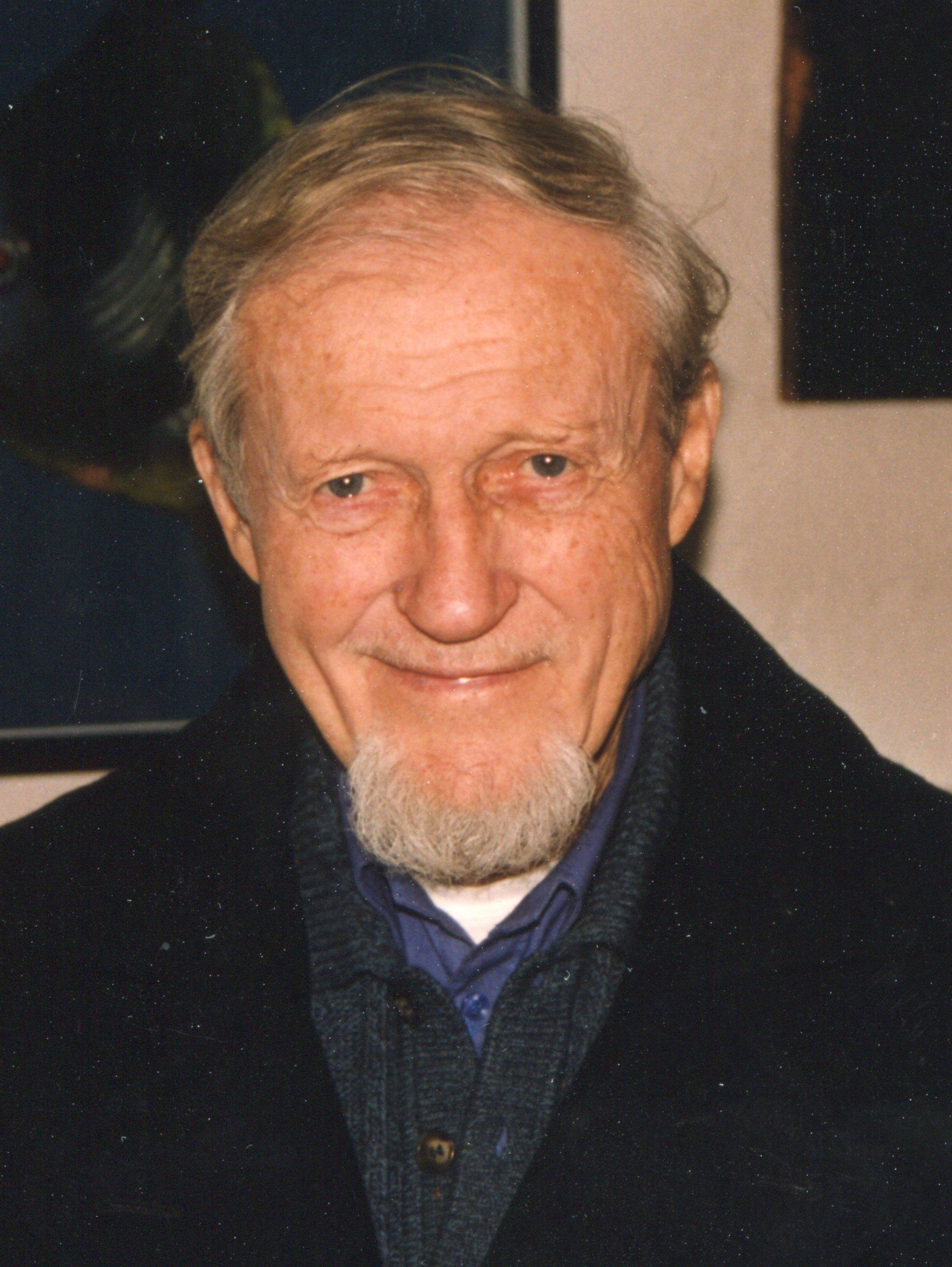

Guidi Alberto

Per avere un racconto affascinante della vita missionaria di p. Guidi Alberto rimandiamo il lettore al libro "Missionario all'Equatore", scritto dallo stesso Padre nel 1989, edito dall'Emi e più volte ristampato. Contiene episodi veramente toccanti e ben documentati nei quali si scoprono le fatiche del protagonista e il suo amore per gli africani.

La famiglia di p. Guidi, quanto a vocazioni era seconda a poche. Basti pensare che delle quattro sorelle della mamma, una, Cesira, si fece suora, mentre le altre tre diedero ciascuna un missionario alla Chiesa. Figlio, infatti, di Matilde è fr. Nando Bartolucci, figlio di Nina è p. Severino Crescentini e figlio di Letizia Sanchini è il nostro p. Alberto. Mamma Letizia non ha avuto la grazia di vedere il figlio sacerdote perché il Signore l'ha chiamata in paradiso a 27 anni di età lasciando Alberto di 5 anni e la sua sorellina, Bruna, appena nata. Anche papà Giuseppe, di professione falegname, seguì ben presto la moglie per cui i due orfanelli furono allevati dagli zii profondamente cristiani.

La mamma di p. Crescentini dice che, da piccolo, p. Alberto era delicatissimo di coscienza. Se, per esempio, sentiva qualcuno bestemmiare, si segnava subito col segno della croce e poi scappava "perché - diceva - dove c'è chi bestemmia c'è il demonio".

Dopo le elementari Alberto manifestò il desiderio di farsi missionario e il suo parroco, don Alfonso Fiorani, lo indirizzò dai Comboniani. Essi, infatti, nell'ottobre del 1928, avevano aperto un seminario a Riccione e, da lì, si spingevano nei paesi della zona per fare animazione missionaria e vocazionale conquistando alla loro causa tanti sacerdoti e bravi giovinetti.

Arrivarono anche al paese di Alberto, e il ragazzino, incoraggiato appunto dal parroco, fu uno dei primi a rispondere sì.

E fu anche uno dei primi ad entrare nella nuova scuola apostolica di Riccione, proprio nell'ottobre di quel 1928. Completate le medie, passò a Brescia per il ginnasio e il 25 luglio 1933 entrò nel noviziato di Venegono Superiore, dove fece la professione il 7 ottobre 1935.

Passò quindi a Verona per il liceo (1937-1941) e a Roma per la teologia (1947-1941).

Consacrato sacerdote nella chiesa del seminario maggiore romano dall'arcivescovo Luigi Traglia il 30 giugno 1940, completò gli studi fino a conseguire la licenza in teologia presso il Pontificio Ateneo Urbano nel 1941.

Trascorse qualche mese a Bologna per lo studio dell'inglese e poi passò a Pesaro come economo della casa e come addetto al ministero. Teniamo presente che proprio in quel periodo il seminario di Riccione si trasferì a Pesaro nella villa Baratoff. Il posto, indubbiamente, era più adatto alla formazione dei futuri missionari che godevano di un bella casa, di vasti cortili e di un bel parco con annessa un po' di campagna.

La generosità di p. Guidi

Si era in tempo di guerra per cui non era facile dar da mangiare a tante bocche, anche se Pesaro fu una della case più fortunate in quanto, essendo in zona agricola, l'indispensabile non mancò mai. Non mancò grazie anche ai giri che p. Guidi faceva in bicicletta nei paesi circostanti predicando e... mendicando.

Scrive p. Domenico Pazzaglia: "Era la fine di giugno del 1944. Il superiore, p. Pazzaglia, raccolse la comunità e disse che c'era l'ordine per tutti di sfollare.

P. Conti, p. Vignato, p. Pazzaglia e un seminarista partirono per Serravalle. P. Furbetta e p. Rognoni per San Lorenzo in Campo. P. Guidi e fr. Guadagnini si offrirono a restare per custodire la casa, sfidando i bombardamenti che imperversavano causa la vicinanza della Linea Gotica.

Nel mese di luglio i fascisti occuparono il seminario. In agosto fu la volta dei tedeschi e in settembre degli alleati.

P. Guidi e fr. Guadagnini, di notte, scavavano delle buche per nascondere qualche cosa del seminario, ma una sera furono sorpresi dai tedeschi i quali li minacciarono con le armi, credendo che nella cassetta che stavano sotterrando ci fossero armi o bombe. Quando videro che si trattava di suppellettili di chiesa, cominciarono a fare la parodia della messa, cantando parole latine con voce da ubriachi (alcuni lo erano davvero).

Nell'intervallo tra la presenza dei fascisti e quella dei tedeschi, p. Guidi offrì alla gente dei dintorni tutto il cibo che era rimasto.

P. Guidi aveva sepolto una motocicletta lasciata dai fascisti nel letamaio vicino alla stalla, ma quando si cercò di recuperarla era marcita. Troppo tempo era rimasta in quel luogo non propriamente adatto a una motocicletta.

I bombardamenti imperversarono. Un giorno tra il cimitero e la casa dei Comboniani caddero 150 bombe di cui venti vicinissime a villa Baratoff, ma questa rimase in piedi per cui i missionari, fedeli al voto che avevano fatto, costruirono il monumento a San Giuseppe che ancor oggi tiene tra le sue mani la casa.

P. Guidi - prosegue p. Pazzaglia - era sempre il primo per il ministero e per le giornate missionarie. Pensava al futuro dei giovani studenti. Siccome si era al tempo in cui i ladri prosperavano, egli divideva i pochi soldi di cui disponeva nelle varie stanze. E il grano venne messo in damigiane di vetro sepolte nel parco con un pino sopra per ricordare il posto esatto. Così, quando dopo il passaggio della guerra venne riaperto il seminario, i seminaristi avevano il cibo per ricominciare".

In Africa

Con la fine della guerra, anche p. Guidi, insieme a una settantina di confratelli in lista d'attesa, poté imbarcarsi per l'Africa. Salpò da Napoli il 24 giugno 1946 sull'incrociatore Duca degli Abruzzi fino a Port Said. Arrivò a Khartum il 10 luglio 1946 e, dopo 13 giorni di battello sul Nilo, giunse a Juba nel Sudan meridionale.

In uno scritto scopriamo i sentimenti di questo confratello al momento della partenza dall'Italia. Dopo la cerimonia di addio tenuta il 7 aprile 1946 nella chiesa di Santa Anastasia di Verona insieme a 73 confratelli, scrisse: "Per me l'Equatore è come una strada che scende verso l'ignoto". Sentendo bisogno di aiuto, si recò privatamente nel santuario di Santa Teresina a Tombetta per chiedere luce e forza alla patrona delle missioni. "Porterò il cuore infuocato di amore al mio Equatore", scrisse. Davvero p. Guidi voleva essere un portatore di amore all'Africa. E fu fedele alla parola data.

Una delle prime cose che lo sorpresero amaramente, ancora durante il tragitto in battello sul Nilo, fu quando a una fermata fu avvicinato da un arabo che gli offrì in vendita un bimbetto nero. "Ma come! Non è finita la schiavitù?", protestò il missionario. "No, no - replicò l'altro - noi vendiamo anche bambini che finiscono a Khartum come schiavetti".

Okaru e Torit sono le due missioni che godettero della sua presenza dal 1946 al 1964. Ad Okaru fu subito nominato rettore del seminario. Dovette tuffarsi nello studio della lingua ed affrontare il nuovo incarico con molta umiltà essendo un novellino.

Fece molto bene, tanto che rimase in quell'incarico per nove anni coprendo anche il ruolo di superiore, fino, ed oltre, la sua nomina a superiore regionale del Bahr el Gebel (1953).

A Okaru seguiva una decina di ragazzi che volevano farsi cristiani. Durante la mattinata pascolavano i maialetti e, alla sera, si recavano alla missione per imparare il catechismo. Ma ecco la prova: alcuni uomini mandati dallo stregone rapirono con forza i ragazzi e li dispersero.

Una domenica mattina ritornarono. Alcuni zoppicavano e altri erano pieni di lividure per le percosse ricevute, ma tutti erano contenti di essere ritornati. Dopo il battesimo tornarono ai loro villaggi e divennero evangelizzatori dei loro coetanei. "Queste cose - scrisse il Padre - ti ricompensano di tutti i sacrifici che hai compiuto per arrivare in queste contrade".

Superiore regionale

Dal 1955 al 1964 fu a Torit sempre come regionale.

A Torit fu testimone della "strana" morte di un suo alunno, il modello della scuola. Probabilmente fu avvelenato dai nemici dei missionari. Il Padre si augurava - allora - di conoscere un giorno la causa di quella morte nell'incontro con il suo piccolo amico nel grande villaggio del Padre in cielo.

Le testimonianze dei confratelli in questo periodo ci mostrano un p. Guidi esemplare, buono con i confratelli, capace di trattare con i seminaristi, tutto proteso alla formazione dei futuri sacerdoti africani e uomo di carattere, in grado di sostenere con chiarezza e lucidità le proprie idee frutto di consiglio con gli altri confratelli.

P. Patroni scrisse nel 1952: "Il seminario sotto la sua direzione procede bene. E' un buon religioso e attende con impegno e dedizione al suo ufficio. Mostra di desiderare molto il ministero tra la gente, anche se è costretto a rimanere in sede per il suo ufficio di rettore".

"Vorrei proprio, ed è il desiderio sommo della mia vita - scrisse - aiutare i seminaristi africani ad essere degni sacerdoti della Chiesa d'Africa che sarà una Chiesa gloriosa".

Formatore di sacerdoti

Per essere coerente con questo suo proposito, fondò la formazione su tre pilastri, o su tre vie che i seminaristi dovevano battere: la Parola di Dio, l'Eucaristia e la devozione alla Madonna.

Sembra che abbia anticipato ciò che il Direttorio per il ministero e la vita dei presbiteri, di recentissima pubblicazione, afferma: "I primi responsabili della nuova evangelizzazione del terzo millennio sono i presbiteri, i quali, però, per poter realizzare la loro missione, hanno bisogno di alimentare in se stessi una vita che sia pura trasparenza della propria identità e di vivere una unione di amore con Gesù Cristo sommo ed eterno sacerdote...". Questi era p. Alberto, sacerdote e formatore di sacerdoti.

Egli sentì fino in fondo la responsabilità dell'ufficio che i superiori gli avevano affidato e, per essere all'altezza del compito, trascorreva molte ore nello studio e ancora di più nella preghiera. Sapeva, infatti, che solo dal Signore veniva a lui la luce per guidare e ai seminaristi la forza per operare. In questa visione di fede fu veramente un rettore "magnifico".

Punto e a capo

L'espulsione del 1964 fu un brutto colpo per p. Guidi, tuttavia non si perse d'animo sicuro che Dio non avrebbe abbandonato la Chiesa del Sudan meridionale. Seguì con trepidazione i seminaristi che, spinti dall'onda della persecuzione, vivevano alla macchia o erano costretti a fuggire nelle nazioni vicine, in particolare in Uganda. Li raggiungeva con lettere in modo da tenere vivo in loro il fervore e l'attaccamento alla loro vocazione.

Intanto, dal 1964 al 1965, divenne superiore della casa di Pesaro. Vi rimase con il piede alzato, pronto a spiccare il salto per qualche missione africana. Fu accontentato.

I motivi di una sua così breve permanenza nel ruolo di superiore vanno ricercati nell'incapacità del Padre di ambientarsi nel clima italiano. "Il mio modo di vedere, di pensare e di agire è troppo diverso da quello dei miei confratelli per cui la cordiale intesa che ho sempre desiderato è molto difficile da realizzare. Inoltre ho capito che anche i ragazzi di oggi sono diversi da quelli del mio tempo per cui non riesco ad entrare in confidenza con loro. Ciò è grave agli effetti della formazione. Perciò credo che sia saggio farmi tornare in missione dove, penso, di poter ancora essere utile".

Nel 1966 venne destinato all'Uganda. Fu a Kangole come coadiutore per alcuni mesi, a Moroto come procuratore dal 1966 al 1967, a Nadiket (1967-1977) come superiore e rettore del seminario diocesano, a Nabilatuk dal 1978 al 1985 come parroco, a Naoi dal 1986 al 1993 come parroco e superiore locale e dal 1993 al 1994 a Matany come addetto al ministero.

In 46 anni di vita apostolica p. Guidi ebbe da sopportare tante sofferenze ma fu protagonista di gioie ben più intense, quelle che gli derivavano dall'apostolato.

"Pericoli nei viaggi, razzie, tragedie tribali, stregoni che si opponevano al mio ministero di catechista tra i bambini, l'espulsione del 1964, la precarietà dei tempi di Amin, di Obote, di Museveni, le carestie con il loro contorno di vittime del 1976-1980, il servizio all'ospedale di Matny tra i malati africani e Karimogiong in particolare... ma anche quanti giovani generosi ho visto salire l'altare, quanti atti di eroismo durante la guerra, quante anime belle che dopo aver incontrato Gesù Cristo gli hanno giurato fedeltà fino alla morte, quanti cristiani che hanno saputo perdonare chi aveva fatto loro del male! Ecco la mia vita missionaria", scrisse.

Due grandi sofferenze

Dalle lettere di p. Guidi balzano fuori due sofferenze che lo torchiarono in modo particolare. La prima era la mancanza di personale qualificato per l'insegnamento nei seminari dove era responsabile.

Abbiamo già sottolineato il grande senso di responsabilità del Padre nella formazione dei futuri sacerdoti africani perciò chiedeva confratelli qualificati. E quale era il suo rammarico (e anche quello dei superiori) quando si sentiva dire: "Manca il personale", "tutti chiedono", "non sappiamo cosa fare".

La seconda sofferenza gli è derivata dalla chiusura del seminario missionario di Pesaro. In una sua lettera del 1976 esprime al p. generale tutta la sua amarezza per la decisione presa dal provinciale d'Italia, e porta una serie di motivazioni atte a far mutare consiglio. Ma tutto fu inutile.

La chiusura di quel seminario lo toccava sulla pelle e nel cuore se consideriamo che lui fu uno dei primi che inaugurò quella scuola apostolica, prima a Riccione e poi a Pesaro, e poi tanto si sacrificò per sostenerla negli anni duri della guerra. Il fatto che non fosse stata colpita dalle bombe, per lui era stato un segno da parte di Dio che il seminario a Pesaro doveva continuare.

Verso la fine

Durante le vacanze in Italia del 1993 (era tornato dall'Uganda nel mese di maggio, e non si sentiva bene) i sanitari gli riscontrarono un tumore all'intestino. Venne operato e si rimise in salute.

Il Notiziario della provincia italiana, nella rubrica CAA sottolinea le tappe del suo ultimo cammino.

"12 luglio '93: P. Guidi Alberto giunge da Pesaro per un intervento di stenosi intestinale. E' ora ricoverato al policlinico di Borgo Roma, nel reparto di chirurgia generale B".

"Dicembre '93: P. Guidi Alberto fu accolto nel reparto di Chirurgia B del Policlinico di Borgo Roma per stenosi del colon discendente. Subì intervento chirurgico con resezione di un tratto dell'intestino. Il decorso post operatorio fu soddisfacente ed ora il Padre sta facendo un periodo di convalescenza con controlli periodici".

Sentendosi bene, in novembre volle ripartire per l'Uganda in modo da potersi dedicare all'assistenza dei malati dell'ospedale di Matany.

La sua non è stata una partenza cervellotica. I medici stessi - e abbiamo la documentazione - gli consigliarono il ritorno in missione, sia per evitare il freddo dell'Italia, sia per una sua maggior serenità psicologica. Si pensava, infatti, che il male potesse permettergli ancora quattro o cinque anni di vita, data l'età e il buon esito dell'operazione. Ma questi mali, si sa, sono un po' misteriosi.

Infatti, a metà febbraio 1994 la situazione peggiorò, per cui dovette rientrare in Italia per essere ricoverato presso il Centro Assistenza Ammalati di Verona dove percorse le ultime tappe del suo calvario.

Il Notiziario del marzo 1994 dice: "P. Guidi Albero, rientrato dall'Uganda, è stato accolto per un breve periodo nella clinica Chirurgica B di Borgo Roma per accertamenti. I risultati furono disastrosi: il male si era diffuso un po' ovunque".

"Al Centro Ammalati - scrive p. Cona - il Padre viveva dell'eredità che aveva accumulato durante i suoi anni di missione. Parlava di apostolato, della Chiesa che si dilatava, delle difficoltà causate dalla guerra... I suoi non erano ricordi sterili, bensì motivo per dare senso alla sua offerta quotidiana. Ultimamente aveva anche grandi dolori, ma non si lamentava, non protestava, offriva le sue sofferenze specialmente per i sacerdoti africani e per la Congregazione. 'Noi preghiamo, e per il resto lasciamo fare al Signore che ha fatto bene ogni cosa', furono alcune delle sue ultime parole".

Scrive p. Crescentini: "P. Guidi è stato un autentico comboniano, entusiasta della sua vocazione missionaria, grande appassionato dell'Africa. Trasmetteva il suo amore per il Sudan e per l'Uganda a tutti coloro con cui veniva in contatto; e dove andava lasciava entusiasmo per la missione".

E il nipote Moratti Flaviano aggiunge: "La vita missionaria per lo zio era al primissimo posto nella sua vita. Per lui, portare aiuto ai poveri e portare la Parola di Dio ovunque costituivano l'unico scopo della sua vita".

Nonostante l'aggravarsi della malattia, chiese di terminare i suoi giorni in Casa Madre, non all'ospedale, perché era perfettamente consapevole della sua situazione e l'aveva accettata con fede, anche se fino all'ultimo ha sperato di guarire per tornare in missione. Nell'imminenza della morte i dolori scomparvero completamente tanto che il Padre disse all'infermiere: "Vedi, quando tutto sembra finito, si incomincia a riprendere". Era il miglioramento della morte.

Spirò serenamente, edificando tutti per il modo con cui accolse "sorella morte" che lo introduceva all'intimità col Signore. A Roma si stava concludendo il Sinodo africano nel quale il Padre aveva riposto tante speranze e per il quale aveva offerto una parte delle sue sofferenze. Da vero comboniano amò l'Africa e gli africani e per loro immolò se stesso.

Dopo i funerali in Casa Madre, la salma proseguì per Colbordolo dove riposa nel locale cimitero. Ai funerali presero parte l'arcivescovo di Urbino, mons. Donato Bianchi, 25 concelebranti, diversi suoi ex alunni e una marea di popolo. Il vescovo ha sottolineato la generosità nel servire il Signore e il coraggio del Padre.

Un ringraziamento particolare fu rivolto al parroco, don Umberto Brambati per il suo affetto fraterno verso p. Guidi, avendolo aiutato in ogni modo durante la sua esperienza a Colbordolo.

"Ricordo con profonda stima e ammirazione p. Alberto - disse don Umberto - quando, durante le vacanze che per lo più trascorreva a Colbordolo, al mattino, silenziosamente, quasi con passo felpato, dalla sua camera si recava in chiesa a pregare per un'ora prima della messa e un'altra ora durante la mattinata... La sua profonda umanità risaltava soprattutto quando parlava confidenzialmente con qualcuno, e se poi il discorso scivolava sulla sua missione, allora la sua parola prendeva vigore, slancio, entusiasmo".

Certamente dal cielo intercede per la Chiesa africana, per il clero indigeno e per l'incremento delle vocazioni missionarie specialmente nella sua terra. P. Lorenzo Gaiga, mccj

Da Mccj Bulletin n. 184, ottobre 1994, pp. 97-104

******

For a fascinating account of the missionary life of Fr Guidi, the reader should go to his book: "Missionario all'Equatore" (unfortunately available only in Italian) which he wrote in 1989. It was published by EMI and has had several reprints. It contains many episodes that are very moving and well documented, and shed a light on the labours of the author and his real love for Africa and the Africans.

His family was not miserly as regards vocations. Of the four girls on his mother's side, one became a nun and the other three each gave a missionary to the Church. Fr. Nando Bartolucci is the son of Matilde, Fr Severino Crescentini's mother is Nina, and our Alberto is the son of Letizia Sanchini. She did not have the joy of seeing her son a priest, because the Lord called her at 27, leaving 5-year old Albert and Bruna, his new-born sister. Their father, Giuseppe, who was a carpenter, soon followed his wife, and the young orphans were raised by an uncle and aunt who were devout Catholics.

Fr Crescentini's mother says that Albert, even as a child, had a very sensitive conscience. If, for instance, he heard someone blaspheme, he would make the Sign of the Cross and run away "because," he would say, "where there is blasphemy, there is the Devil".

Straight after primary school Alberto declared that he wanted to be a missionary, and the parish priest, Don Alfonso Fiorani, pointed him towards the Comboni Missionaries. They had opened a seminary in Riccione in October 1928, and from there went round the towns and villages in the area for missionary animation and vocation promotion, and won over a lot of priests and good youngsters. They eventually reached Alberto's village, and the lad, encouraged by the parish priest, was among the first to come forward.

Thus he was also one of the first to enter the new Junior Seminary of Riccione, in the October of the same year. He went through to Brescia for the first years of grammar school, then entered the Novitiate at Venegono Superiore on 25th July 1933. He made his first Vows on 7th October 1935.

He then went to Verona for his Philosophical and Classical studies (1935-37) and then to Rome for Theology (1937-41). He was ordained in Rome by Archbishop Luigi Traglia on 30th June 1940, and then completed his studies, gaining an STL at the Pontifical Urban University (Propaganda) in 1941.

After some months in Bologna studying English, he was sent to Pesaro as local bursar and for pastoral ministry. Just at that time, the Junior Seminary was transferred from Riccione to the Villa Baratoff at Pesaro. The place was certainly much more suitable for the formation of future missionaries: there was a fine house with a large playground, beautiful grounds and even a piece of arable land.

The generosity of Fr Guidi

It was wartime, so quite a difficult task to feed so many mouths, even though Pesaro was one of the luckier houses, in that the necessities could always be found in the surrounding countryside. That they were found is thanks largely to Fr Guidi, who went round all the area on a bicycle, preaching and... begging.

Fr Domenico Pazzaglia writes: "At the end of June 1944 the superior called the community together and said that an order had come for everyone to move away. Fr Conti, Fr Vignato, Fr Pazzaglia and a seminarian left for Serravalle; Fr Furbetta and Fr Rognoni for San Lorenzo in Campo; Fr Guidi and Bro Guadagnini volunteered to stay behind to look after the house, despite all the bombing in the area, which was very near the Gothic Line.

In July, the Fascists occupied the seminary. In August it was the turn of the Germans, and in September, the Allies.

Fr Guidi and Bro Guadagnini would go out some nights and bury some of the seminary property, to hide it. Once they were caught by German soldiers, who threatened to shoot them, thinking the box they were burying contained weapons or bombs. But when they saw that the contents were just church vessels, they began to make fun of the two, singing Latin words in drunken voices (some of them didn't have to pretend to be drunk).

In the pause between the occupation of the Fascists and that of the Germans, Fr Guidi distributed all the food they had left to the people living nearby. He even buried a motorcycle which the Fascists had left behind, in a dunghill near the stable. But when they went back later to bring it out, it had rusted and rotted away: too long in the wrong garage...

The bombing went on and on. One day, about 150 bombs fell between the cemetery and the house. Some of them were really close to Villa Baratoff, which remained standing; later the missionaries kept the promise they had made, and erected the statue of St Joseph which can still be seen, with the house in his hands.

"Fr Guidi," continues Fr Pazzaglia, "was always ready for ministry or Mission Appeals. He always thought about the boys. Since there were a lot of thieves around, he divided up the little money he had and kept it in different rooms. Cereals that he collected were put in glass wine jars and buried in the grounds, with pines planted over them to mark the spots. When the seminary was reopened after the War, the seminarians had some food to get on with."

In Africa

The end of the War also meant that Fr Guidi, along with three-score other confreres on the waiting list, was at last able to leave for Africa. He sailed from Naples on 24th June 1946, on board the cruiser Duca degli Abruzzi, and landed at Port Said. He reached Khartoum on 18th July, and after 13 days by boat down the Nile, he arrived at Juba, in Southern Sudan.

A letter shows his feelings on leaving Italy. He wrote after the departure ceremony held in Santa Anastasia in Verona on 7th April 1946 for 74 missionaries. "For me the Equator is like a road leading into the unknown," he wrote. But he had made a private pilgrimage to St Theresa of Lisieux at her shrine at Tombetta, to ask the Patroness of the Missions for light and strength, and he was able to add: "I will take a heart burning with love down to my Equator." Indeed, his great wish was to be a bearer of love to Africa. And he remained faithful to his word.

One experience that shocked and surprised him while still sailing down the Nile was when an Arab approached him and offered to sell him a small child. The missionary was indignant: "Do you mean to say that slavery still exists?!" "Of course!" came the reply. "We sell even children: there are lots of them in Khartoum."

Fr Guidi spent from 1946 to 1964 in just two missions: Okaru and Torit. In Okaru he was immediately appointed Rector of the seminary. He had to plunge into the study of the language and tackle his new job at the same time - which he did with great humility, being a novice...

He did so well that he remained in the job for nine years. He was also local superior, up to and even after his appointment as Provincial Superior of Bahr el Ghebel (1953).

He had a dozen lads in Okaru who were preparing to become Christians. They would look after piglets by day and come for catechism in the evenings. They even had to undergo a form of persecution. One day the whole lot were kidnapped by some men sent by a local medicine man, and dumped in various localities far from the mission. They straggled in on a Sunday morning: some were limping and others were covered in bruises from the beatings they had been given, but they were all happy to be back and to continue. After their Baptism they returned to their homes and became evangelisers of their playmates. "Episodes like this," wrote Father, "make all your efforts and sacrifices to reach here worthwhile."

Regional Superior

Fr Guidi lived in Torit from 1955 to 1964 as Regional Superior.

There he witnessed the "strange" death of one of his pupils, the best in the school. He was probably poisoned by enemies of the mission. Father said - then - that he would look forward to finding out for sure one day, when he met his little friend again in the Father's Village of Heaven.

The comments of confreres during this period show Fr Guidi as an exemplary man and priest: kind to his confreres, able to work well with the seminarians, wholly taken up with the formation of those future African priests; a man of character, able to stand up for his ideas clearly and firmly - yet forming those ideas through discussion and consultation with his confreres.

In 1952 Fr Patroni wrote: "The seminary is running well under him. He is a fine religious, and does his work with commitment and dedication. He shows an intense desire for pastoral ministry, though he realises that he is often tied down by his office as Rector."

He himself wrote: "I really want - and it is the supreme wish of my life - to help these African seminarians to become worthy priests of the Church in Africa - and it will be a glorious Church."

Formator of priests

To keep to his intention, he based his formation on three pillars, or the three paths the seminarians had to walk: the Word of God, the Eucharist and Devotion to Our Lady.

He seems to have anticipated what can be found in the very recent Directory of Ministry and Priestly Life: "Those who are responsible in the first place for evangelisation in the Third Millenium are the priests who, in order to carry out their task must nourish in themselves a life which is a clear picture of their identity, and live in unity of love with Jesus Christ, the Eternal High Priest..." Such was Fr Alberto, priest and formator of priests.

He was fully conscious of the responsibility entrusted to him by his superiors, and to try to be worthy of it he spent long hours in study, and even longer hours in prayer. He knew that only from the Lord could he receive the light to guide, and the seminarians the strength to follow. In this vision of faith he was a true "Rector magnificus".

Starting all over

The expulsions in 1964 were a bitter blow for Fr Guidi, though he did not give up the certainty that God would never abandon the Church of the Southern Sudan. He followed anxiously the fate of the seminarians. Scattered by a wave of persecution, some fled into the bush, while others made their way to neighbouring countries, especially Uganda. He managed to keep in touch by letter, to sustain their fervour and their attachment to their vocation.

In the meantime, he was superior at Pesaro from 1964-65, though he stayed there with one foot in the air, ready to jump as soon as a place in the missions in Africa was offered him. The chance came.

The reasons why he did not last long as superior must be found in his inability to adapt to the Italy in which he found himself. "My way of seeing things, my ideas and my behaviour were too different from those of my confreres to make it possible to reach the cordial understanding that I always wanted. I even realised that the boys of today are not like the ones of my own times, and I could not win their confidence. This is no help at all for formation. So I think it is wise to let me go back to the missions where, I think, I can still be of some use."

He was assigned to Uganda in 1966, and went first to Kangole for a few months as associate pastor. He spent a year at Moroto as procurator, then a decade (1967-77) at Nadiket as superior and Rector of the Diocesan seminary; from 1978 to 1985 he was Parish Priest at Nabilatuk and added the role of local superior when he went to Naoi in 1986. From 1993-4 he helped in pastoral ministry at Matany.

His 46 years of missionary life gave him a number of moments of pain, but he also experienced intense joys, those that one finds in the active apostolate. "Dangers on journeys, from rustlers, tragedies among the tribes, medicine men who opposed my teaching the catechism to children, the expulsion of 1964, the uncertainties of the times of Amin, Obote and Museveni, the terrible droughts with their many victims, especially between 1976 and 1980; pastoral service in the hospital at Matany, with sick people from all over the country, besides the Karimojong... but there were also the many generous young men, the ones I saw become priests; the acts of heroism during the war, the many saintly souls I came across, who had encountered Christ and had sworn fidelity to him until death; the numerous Christians who found the courage to forgive those who had harmed them. This is my missionary life!"

Two great sufferings

Fr Guidi's letters stress two things that made him suffer greatly. The first was the lack of trained personnel for the seminaries where he was put in charge. His great feeling of responsibility for the formation of future African priests has already been underlined; this made him request qualified confreres rather forcefully. He was bitterly disappointed - as were the superiors - when they had to answer: "There is no-one", "everybody is asking", "we don't know what to do".

The second great sadness also had to do with a seminary: the closure of the missionary juniorate at Pesaro. In a letter of 1976 to the Superior General he expresses all his delusion at the decision of the Provincial of Italy, and lists all the reasons he can think of to ask for a reprieve. It was no use. Of course, that particular closure hit him personally: he had been one of the pioneer students when it started, first at Riccione and then Pesaro, and then had made such great sacrifices to keep it going during the war years. The fact that it had not taken any direct hit from a bomb was one of the clear signs, for him, that God wanted the seminary at Pesaro to carry on.

Towards the end

During his leave in Italy in 1993 (he had come up in May, and was not feeling well) the specialists found an intestinal tumour. He had an operation, and seemed to recover well.

The Provincial Newsletter of Italy outlines the next stages of his final journey, under the feature "CAA" (Centre for the Assistance of Sick Confreres): "On July 12, Fr Guidi arrived from Pesaro for an operation on an intestinal obstruction. He is at present in the Polyclinic of Borgo Roma, Surgical Ward B".

"December 1993: Fr Alberto Guidi was admitted to Surgery B for an operation on a narrowing of the descending colon. Part of the intestine was removed. His progress after the operation was satisfactory, and he is now convalescing, with regular check-ups."

When he was feeling well in November, he had decided to return to Uganda to continue his pastoral care of the patients in Matany hospital. It was not a wilful decision; the doctors (as documents show clearly) advised him to go back, both to avoid the Winter cold in Italy, and because the psychological effect would have been to make him more serene. They believed, in fact, that he still had four or five more years, considering his age and the success of the operation. But such things, as we know, have their element of mystery.

In fact, his conditioned worsened dramatically in February 1994, and he had to return to the CAA in Verona, where he travelled the last steps of his Calvary. The Newsletter of March states: "Fr Alberto Guidi, having returned from Uganda, went into the Surgery Ward B of Borgo Roma for tests. The results were disastrous: the cancer had spread more or less everywhere."

"During those days at the CAA," writes Fr Cona, "he lived on the accumulated memories of his mission years. He talked about the apostolate, about the growing Church, the problems caused by the wars... They were not sterile memories; they served to give a meaning to the offering he made daily. Towards the end he was in great pain; he never complained or protested, but offered it up especially for African priests and for the Institute. `We pray, and as for the rest, we leave it to the Lord who has done all things well' was one of his last expressions.

Fr Crescentini writes: "Fr Guidi was an authentic Comboni Missionary, enthusiastic about his vocation, with a great passion for Africa. He transmitted his love for the Sudan and Uganda to everyone he met; and wherever he went, he left behind him some enthusiasm for the missions."

His nephew Flaviano Moratti adds: "For my uncle, missionary life occupied the foremost place. The only scope of his life was to bring help to the poor, and the Word of God everywhere."

In spite of his increasing pain, he asked to spend his last days in the Mother House rather than the hospital, because he was fully aware of the situation, and his faith had given him the strength to accept it, even though he never quite gave up the thought of going back to the Mission one day. When death was imminent his pain left him, and he said to the nurse: "You see, when everything seems to be over, you start improving!" It was the final flicker of the candle before going out.

He died peacefully, impressing everyone by the way he welcomed "Sister Death", who came to lead him into the intimacy of the Lord. The African Synod was drawing to an end in Rome: Father had placed great hope in it, and had offered up his sufferings for it, too. True to Comboni, he loved Africa and the Africans, and immolated himself for them.

After the Requiem in the Mother House, the body was taken to Colbordolo, and buried in the local cemetery. At the funeral were the Archbishop of Urbino, Mgr Donato Bianchi, 25 concelebrants, many of his former students and a sea of people. The Archishop stressed the father's generosity in the Lord's service and his great courage.

The parish priest of Colbordolo, Don Umberto Brambanti, who had helped Fr Guidi a lot during periods spent in the parish, recalled those days: "I have a deep esteem and respect for Fr Alberto. He spent most of his holidays at Colbordolo, and he would get up and creep out early in the morning, and spend an hour in prayer in the church before Mass, and another hour during the morning... He had a real human touch, which showed particularly in private conversations; and if Africa happened to come into the conversation, then his words became even more lively, and he spoke with enthusiasm and excitement."

He is certainly interceding for the African Church, for the local clergy and for an increase in vocations, especially in his beloved area.