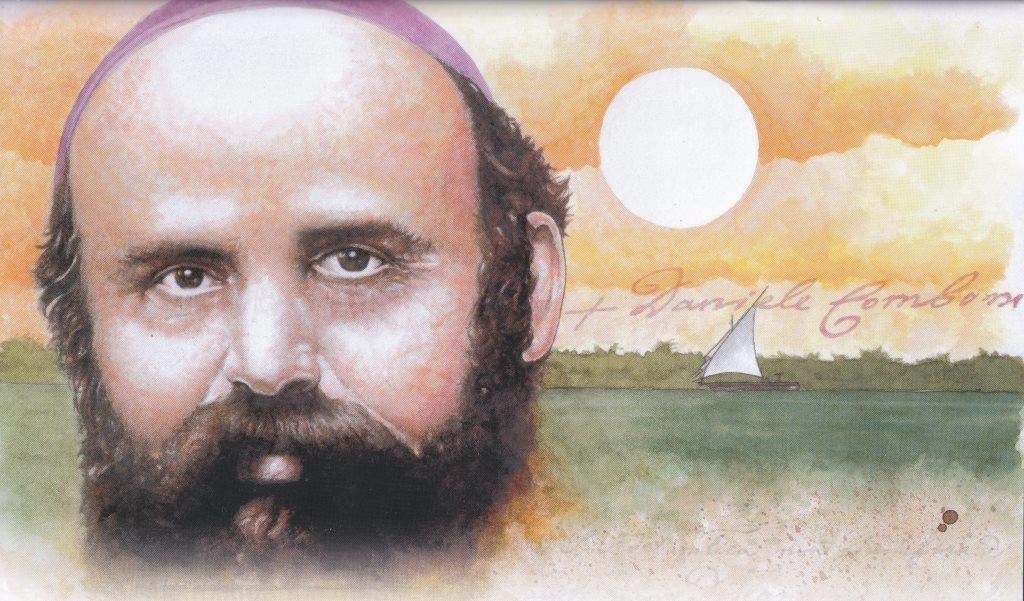

Daniele Comboni

Missionari Comboniani

Area istituzionale

Altri link

Newsletter

Tuesday, October 20, 2020

“Wherever Comboni founded a mission, he would immediately begin a school, since his missionary methodology did not only contemplate the formation of apostles for the faith, but also “apostles of civilization” (Comboni, 1870, W226). The early Comboni missionaries who returned to Sudan following the Mahdya continued with the same missionary method. In a country where the education system was basically reduced to Quranic schools’ networks - where you could only study the Quran, the Fiqh (i.e. the Islamic Jurisprudence), the Arabic language and the Basics of Arithmetic (Seri-Hersch, 2017, p.3) - this seemed the most appropriate approach.”

COMBONI COLLEGE:

THE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION WITHIN AN INTER-RELIGIOUS CONTEXT

Introduction

Wherever Comboni founded a mission, he would immediately begin a school, since his missionary methodology did not only contemplate the formation of apostles for the faith, but also “apostles of civilization” (Comboni, 1870, W226). The early Comboni missionaries who returned to Sudan following the Mahdya continued with the same missionary method. In a country where the education system was basically reduced to Quranic schools’ networks - where you could only study the Quran, the Fiqh (i.e. the Islamic Jurisprudence), the Arabic language and the Basics of Arithmetic (Seri-Hersch, 2017, p.3) - this seemed the most appropriate approach.

Comboni College Khartoum (CCK) foundation

School and mission seemed to be inseparable in Sudan until 1924, when Msgr. Paolo Tranquillo Silvestri was appointed Apostolic Vicar of Khartoum. In 1925, the Bishop closed two Catholic all-boys schools - the only ones then existing in Sudan - and rented out the building where the only all-girls school was located.

The Vicariate was experiencing economic problems, and the bishop preferred to concentrate his limited financial and human resources on what is now South Sudan. On the other hand, Msgr. Silvestri - who was well aware of the impossibility of converting the Muslim majority in the North - decided to limit our presence in the area to the minimum necessary, to facilitate the logistical access towards the missions of the South (Villa, 1932).

At that time, the Congregation was led by Fr. Paolo Meroni, who had a broader concept of mission and a different perception on the importance of our presence in the North. The confreres attending the General Chapter of 1925 came up with the decision of founding a school in Khartoum. This institute would be named after our founder, since it had been decided to introduce the cause of his canonisation.

Other Churches and national communities had founded primary schools over the four years of absence of Catholic all-boys schools from Sudan. It seemed, therefore, especially necessary to establish a secondary school where students from several primary schools could merge. Since secondary or high schools were called “colleges” in the English system, the school founded in 1929 was called “Comboni College Khartoum” (CCK), and it would have had technical and commercial orientation in order to respond to the country’s needs at that time.

The colonial government granted permission to found the school on two conditions. The first was related to the teaching staff’s academic qualifications. The lack of Comboni Missionaries with the necessary academic certificates brought the Congregation to invite the Canadian Teaching Brothers, with the responsibility of forming the teaching staff, while the Comboni Missionaries - who were the school’s owners - would have been responsible for its administration.

The second condition related to the authorization process (second version) which prohibited the enrolment of sudanese students in the new school. Moreover, the Gordon Memorial College proposed a curriculum which had been conceived to meet the colonial administration’s requirements. This was the one and only secondary school in the country and belonged to the government (Vantini, 2005).

The latter condition had to do with the English authority’s concern, according to which, the opening of missionary schools to Muslim students could hurt the local peoples’ feelings, since the experience of the Mahdya was still an open wound - and could fuel “dangerous” independence leanings. Especially since the revolution of 1924 in the neighbouring North, where the new Egyptian government behaved in a very hostile way towards the English people.

Quality and leaders-formation for the independent Sudan

The Sudanese press became the channel through which the people’s desire to have access to a better quality educational offer was expressed in the thirties of the last century. Moḥamed Aḥmad Maḥjūb, amongst the local leaders, wrote an article in the local newspaper Al-Fajr asking from the colonial government the reform of the objectives and of the education contents given at the Gordon Memorial College, so as to bring them up to par with the standards of the British system. A few months later, a second piece, by the same author, bore an unequivocal title: “Give us education and leave us alone” (Aḥmad Maḥjūb, 1935, pp.1065-1066).

Along these lines, the second British Under-Secretary of State, Sir Lancelot Oliphant, accused the British authorities in Sudan to neglect “the education of the natives and to concentrate solely on efficient government” (Foreign Office 407/219, quoted by Warburg, 2003, p.97) on the 13th of October 1936.

Sayed Abdel Rahman el-Mahdi - the posthumous child of Muḥammad Aḥmad Al-Mahdi, who had destroyed the missionary work carried out by Daniel Comboni - visited the Comboni College on the occasion of the prize-giving to champions of the different sports tournaments in April 1938. The religious and political leader was so impressed by the quality of the institution that he donated 50 Sudanese pounds for scholarships and enrolled three members of his own family in the school in 1940 (Vantini, 2005, pp. 514-515).

At that time, the Comboni College represented a clear example of international education community made up of 150 Egyptian students, 48 Syrians, 32 Greeks, 26 Italians, 16 Armenians, 13 Palestinians, 2 Indians, one Ethiopian, a Polish, one Yugoslavian and 48 Sudanese. The latter, finally, have already had access to the CCK. With regard to religion “208 were Christians, 104 were Muslims, 31 Jews and 2 Hindus” (Vantini, 2005, p.515).

In 1933, the Comboni College became a centre for Oxford High School examination which enabled its students to pursue their education at any university in the world. This level meant a huge investment by the Congregation in adequately preparing the Comboni Missionaries assigned to teach in the school. A quality indicator of the teaching standards is given by the fact that 92.5% of the students who sat in 1950 for the Oxford Exam were able to pass it. Furthermore, in 1949, the CCK became London Institute of Chartered Accountants’ Examination Centre.

Sudan achieved Independence in 1956, and, in 1966, Sadiq Al-Madhi - who was a graduate student of the CCKs - was elected as Prime Minister.

Sudanisation and equity

Sudanese government ordered the expulsion of foreign missionary groups in the South in 1964; the intentions of those who also wanted to expel the missionary groups in the North were stopped thanks to the reaction of some graduates from CCK who then formed part of the government (Vantini, 2005, p.522).

However, another event had strong impact on the institution: the 1964’s disorders. On the uprising, Southern Sudanese and Sudanese fought against each other in the capital. Most of the CCK’s foreign lay teaching staff left the country and this also had great effects on the educational quality.

Since then, the process of sudanisation of the teaching staff quickened, and the concept of equity achieved greater emphasis especially when the second civil war (1983-2005) obliged thousands of Southern Sudanese to move to the North.

The creation of a university section

Even if timetables, teaching staff and place had already been decided, post-secondary program’s creation was prevented by the riots of 1964.

In 1999, some parents of students frequenting the school primary section asked Fr. Beppino Puttinato, who was in charge of the school, to let their sons continue their academic studies at the Comboni College.

The Ministry of Higher-Education and Scientific Research of Sudan approved the Comboni College of Science and Technology (CCST) on the 15th of April in 2001 thanks to the contribution of those fathers. They all were Muslim Sudanese citizens passionate by the Charisma of Comboni.

The CCST became the one and only Christian higher education institution throughout the country. Its several university curricula currently admit 54% of Sudanese students and 46% of foreign pupils mainly coming from refugee families of South Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia.

An evolution marked by dialogue with society

The CCK’s foundation represented the response of the Congregation towards the abandonment of an active missionary presence in Sudan, the land marked by the steps of the Founder. In that way, pastoral care and education could be given to the Christian minority, along with obtaining a launching pad for dialogue with an Islamic majority society. The lack of quality schools turned CCK into a reference point in which generations of Muslim and Christian leaders were educated together.

With the launching of new schools in the country, along with a Sudanese curriculum rather than an international one, the institution emphasised the equity point.

High-school filled its classrooms with South Sudanese students, and the post-secondary section facilitated access to higher education for students coming from displaced and refugees families from South Sudan and Eritrea. This does not prevent the university section to keep its doors open to well-off societal sectors particularly interested only in the study of Spanish and Italian languages.

The evolution in time of the features offered by the institution went hand in hand with the evolution of the concept of mission itself. In fact, it was started in reaction to a reductive vision of mission limited to the conversion of people who had not yet heard of Christianity

With the passing of time, Comboni College has evolved according to a vision that understands mission as dialogue at the service of the building of the kingdom in collaboration with Muslim friends.

For instance, this approach finds concrete expression by means of the service that the post-secondary section carries out through its activities in the field of palliative care. Muslims and Christians are formed to approach to the Father’s mercy anyone who is suffering from a chronic or a terminal disease.

Another example of this approach is represented by the business incubator created by the CCST through which we promote a model of entrepreneurship that respects the environment, meets the social needs, and encourages the economic integration for those most in need.

Comboni College historical evolution has also affected the way of developing the ministry for those missionaries who worked there. The early Comboni Missionaries ran a secondary school composed by a majority of foreign and Christian students, while the teaching, per se, had been entrusted to the Canadian Brothers (1929-1935). After these left, the congregation had to prepare well-qualified missionaries for this ministry. Some of them never worked in parishes, but spent the rest of their missionary lives enlightened by the icon of Jesus as a Teacher.

In recent years our presence has decreased, and the teaching - as much as the administration - are carried on in collaboration with the local staff. Here are included some Muslims and Christians who had studied at the primary and secondary school of the CCK, and who graduated at the CCST. They are the ones who continue along the path of the mission and who provide new insights on the institution.

Bibliography

Aḥmad Maḥjūb, M. (1935) ‘ʿallimūnā’, Al-Fajr, pp. 1965-1966.

Seri-Hersch, I. (2017) ‘Education in Colonial Sudan, 1900-1957’, Oxford University Press USA, 1(May), pp. 1-26. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.12.

Vantini, G. (2005) La missione del cuore. I comboniani in Sudan nel ventesimo secolo. Bologna: EMI.

Warburg, G. (2003) Islam, Sectarianism and Politics in Sudan Since the Mahdiyya. London: Hurst and Company.

Fr. Jorge Carlos Naranjo Alcaide

Comboni Missionary

Khartoum (Sudan)